(ENG) Akabane-Iwabuchi: Walking Through a Millennium of Water, War, and Resilience in Northern Tokyo

Akabane-Iwabuchi is a microcosm of Tokyo’s broader narrative: the engineering, the spirit, the industry, and the nature simultaneously.

How did water shape the identity and safety of Tokyo?

How did military landmarks transform into peaceful urban green spaces?

Can I still visit the military shrine of the general?

Listen to the historical stories told in detail (For subscribers only)

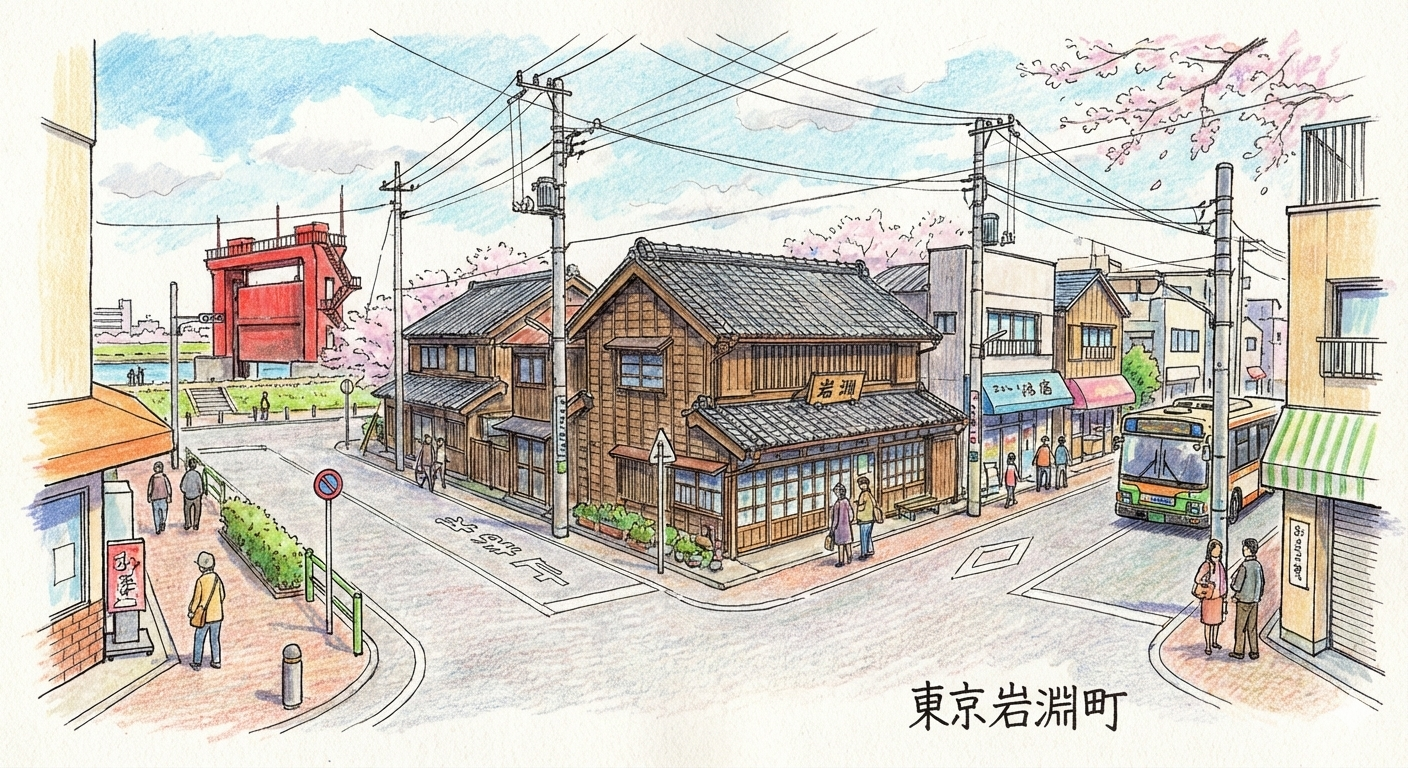

At the strategic confluence of the Arakawa and Sumida Rivers lies Akabane-Iwabuchi, a landscape that serves as a profound palimpsest of Tokyo’s survival. Historically known as Iwabuchi-shuku, this district was a vital gateway on the Iwatsuki Kaido, the prestigious road also known as the Nikko Onari Kaido, which connected the Shogun’s seat in Edo to the northern provinces. Today, this history is not merely a memory buried beneath urban sprawl; it is a discernible, walkable reality. From the formidable iron gates regulating the river's flow to the ancient temple grounds that have surveyed centuries of change, the narrative of this northern boundary is etched into the very topography. To understand the modern equilibrium of Tokyo, one must first trace the scars and triumphs of this riverfront—a place where the city’s existence was negotiated through engineering, spiritual grit, and the enduring resilience of its people.

The Engineering Saga of the "Red Gate"

For centuries, the Arakawa River was a temperamental neighbor, its frequent inundations threatening the low-lying heart of the capital. The management of this waterway was never a mere municipal task; it was a strategic necessity for the sovereignty of the Japanese state. Following the catastrophic flood of 1910, the government initiated the Arakawa Discharge Channel project, a monumental feat of civil engineering designed to divert the river’s fury away from the city center.

A Visual Timeline of Human Adaptation

The Old Iwabuchi Water Gate, famously known as the Red Gate, stands as a sentinel of the first era of modern flood control (1911–1930). The project was an immense undertaking, requiring the acquisition of 1,088 hectares of land and the displacement of 1,300 households—a staggering social cost paid for the collective safety of millions. For decades, the Red Gate functioned as the primary shield against the rising tides of the Arakawa.

By the 1970s, however, the very ground beneath the gate betrayed it. Decades of industrial groundwater extraction caused the slow violence of land subsidence, rendering the gate’s height insufficient against revised safety standards. This environmental shift necessitated the 1973 construction of the New Iwabuchi Water Gate (Blue Gate). For the modern traveler, the juxtaposition of these two structures—the weathered red iron and the functional blue steel—offers a visual timeline of human adaptation to a shifting planet. To further unearth the technical complexities of this struggle, one can visit the adjacent Arakawa Museum of Aqua (amoa), which serves as a repository for the region's disaster prevention history.

"The Red Gate represents a Resilient First-Generation Defense, symbolizing the immense efforts of engineers who worked without the aid of modern technology to secure the city’s future."

While the Red Gate stands as a mechanical sentinel, the residents of Iwabuchi historically sought a different kind of protection on the heights above the riverbanks.

The General’s Camp and the "God of Victory"

The geography of Akabane-Iwabuchi is defined by its dramatic elevations. The Akabane heights have long served as a natural vantage point, providing a topographical advantage for those seeking to project military power toward the Musashi Province.

A Thousand-Year Military Continuity

In 784, the legendary general Sakanoue no Tamuramaro reportedly established a military camp here during his campaigns to the east. Surveying the landscape from this high ground, he founded the Akabane Hachiman Shrine, enshrining the Hachiman deities to secure lasting military success. The concept of the "God of Victory" (勝負之神) established here over a millennium ago has proved remarkably durable; where ancient warriors once sought "military luck," modern visitors now petition for success in career, competitive examinations, and personal endeavors.

This strategic importance displays a striking continuity. The same geographic vantage point that served a 9th-century general was utilized in the 20th century by the Imperial Army for modern defense and industrial oversight. To stand at the shrine today is to occupy a space that has been synonymous with power and protection for over a thousand years, looking out over the same river confluence that once dictated the movements of armies.

Liquid Heritage: Groundwater and the Iwabuchi Spirit

During the Edo period, Iwabuchi-shuku was a bustling nexus of commerce. Long before the 1928 opening of the New Arakawa Bridge, the Iwabuchi Ferry was the sole method for crossing the river. Historical records even describe the elaborate boat bridges specifically constructed when the Shogun’s procession traveled the Nikko Onari Kaido. While the physical structures of the post town have largely vanished, leaving only the Iwabuchi-shuku Post Town Office Site Stone Monument as a fragile trace, the area's spirit remains preserved in a liquid state.

Tasting the History of the Post Town

Koyama Brewery (now Koyama Honke), founded in 1877 or 1878, stands as the oldest enterprise in the district. Their survival across three centuries is intrinsically tied to the invisible geography of the region: the underflow water originating from the Chichibu mountain range. While the world above ground was transformed by railways and bridges, the brewery continued to draw from the same pure veins of groundwater that sustained the travelers of the old highway.

To sample their Daiginjo is to engage in an act of "tasting history"—consuming the same mineral essence of the landscape that has remained unchanged since the days of the ferry. The brewery represents a commercial resilience that, like the river itself, flows beneath the surface of the modern city.

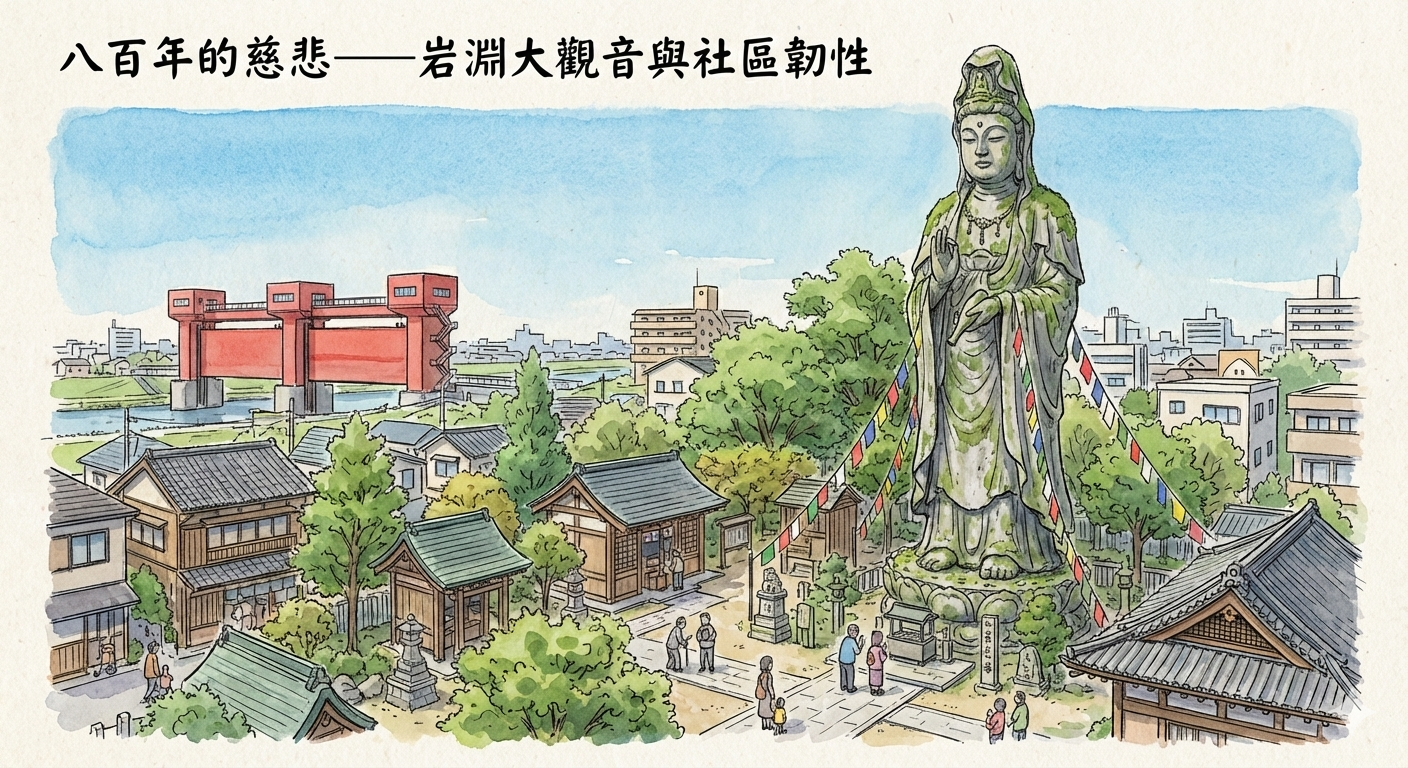

The 800-Year Mercy of the Great Kannon

If the water gates represent a top-down, state-funded approach to survival, the spiritual landscape of Akabane-Iwabuchi reveals a "bottom-up" communal response to disaster. This is nowhere more evident than at Shoko-ji Temple, a site of quiet contemplation with an 800-year history.

Spiritual Defense Against the Elements

Within the temple grounds stands the Iwabuchi Great Kannon. Unlike the engineering marvels funded by national taxes, this statue was a product of localized collective sacrifice. In an era before massive flood channels, the residents of Iwabuchi faced the frequent plagues and floods of the Arakawa with spiritual solidarity, pooling their gold and resources to erect this Kannon as a plea for protection.

For the deep-traveler, Shoko-ji offers a profound contrast: the Red Gate is an engineering defense, while the Great Kannon is a spiritual one. Both are monuments to a community that refused to be defeated by the volatile environment of the river’s edge. This temple remains a testament to the deep collective memory of a people who found strength in faith when the waters rose.

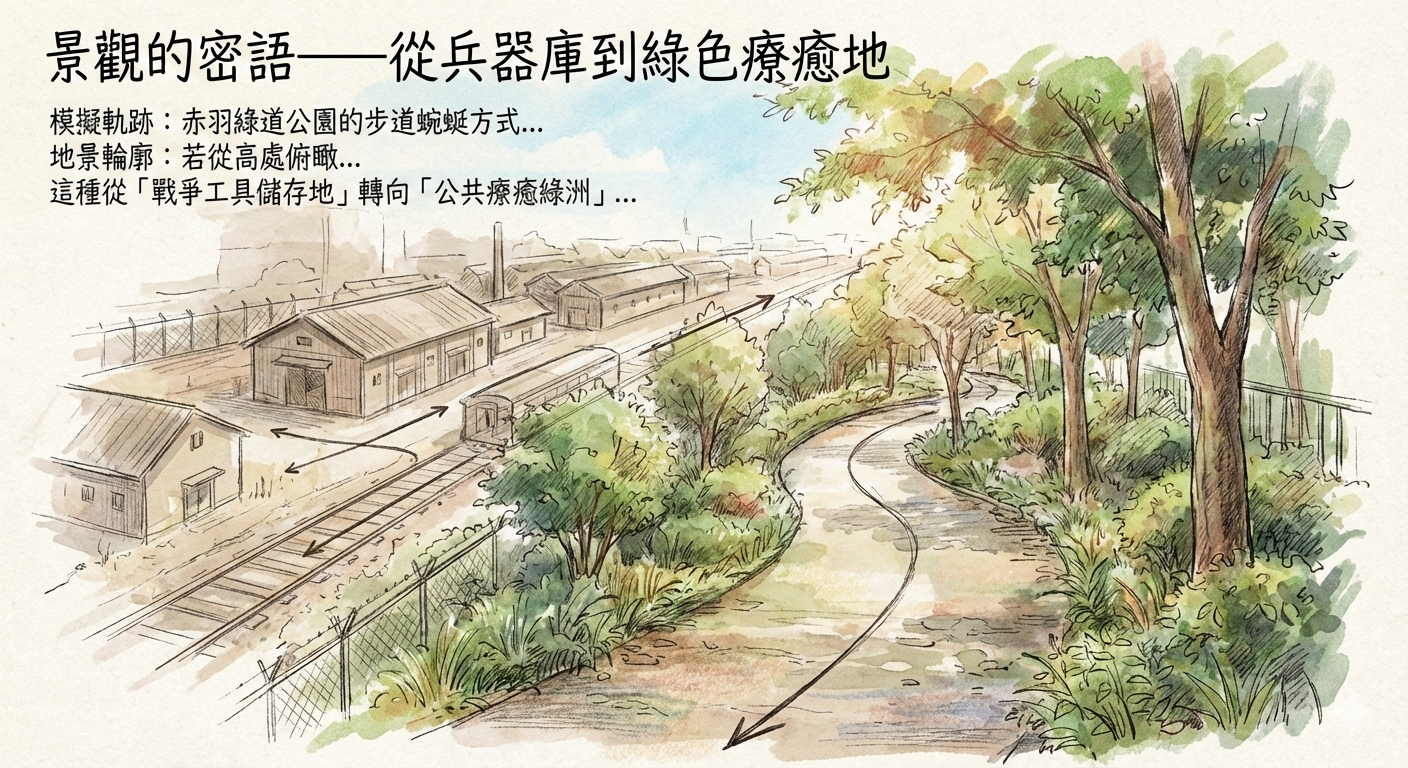

From Arsenal to Oasis: The Landscape’s Hidden Healing

In the mid-20th century, the functional identity of the region underwent a drastic shift. The strategic advantages of water and rail transport led to Akabane becoming a military industrial center, housing massive weapon depots and ammunition storage for the Japanese Army.

Landscape Whispers of a Martial Past

Today, these sites of conflict have been reclaimed as public green spaces, specifically Akabane Nature Observation Park and Akabane Green Road Park. However, the history of the land has not been erased; it has been repurposed. Discerning walkers will notice that the paths in Green Road Park follow the precise curves of the old military railway tracks that once transported munitions from the depots to the front lines.

This evolution represents a process of "landscape healing." What were once high-security sites of industrial warfare are now "Healing Oases" for the public. This transformation is the ultimate expression of Akabane-Iwabuchi’s resilience—the ability to take the scars of a martial past and cultivate them into a space for ecological restoration and community peace.

The Resilience of the Northern Gateway

The story of Akabane-Iwabuchi is a microcosm of Tokyo’s broader narrative. It requires "layered observation"—the ability to see the engineering, the spirit, the industry, and the nature simultaneously. From the red iron of the decommissioned water gate to the ancient prayers at Hachiman, this district proves that urban survival is never the result of a single effort, but a sophisticated tapestry of human ingenuity and communal grit.

In an era of rising waters and shifting global landscapes, what can the Red Gate and the Great Kannon teach us about the enduring necessity of both science and spirit? Perhaps they remind us that a city's true strength lies not just in how it builds for the future, but in how meticulously it remembers its past.

For more deep-history explorations of Tokyo’s hidden corners, subscribe to Lawrence Travel Stories.

Planning Your Walk Through History

How to Get There

- Tokyo Metro: Take the Namboku Line to Akabane-Iwabuchi Station.

- JR Lines: Use JR Akabane Station (Saikyo, Keihin-Tohoku, and Utsunomiya Lines).

Recommended Historical Walking Loop

- Akabane Hachiman Shrine: Ascend the heights to trace the site of Sakanoue no Tamuramaro’s 8th-century camp.

- The Iwabuchi Water Gates: Survey the riverfront to compare the 1930 Red Gate and the 1973 Blue Gate.

- Arakawa Museum of Aqua (amoa): Dive into the technical history of the Arakawa Discharge Channel.

- Shoko-ji Temple: Pay respects to the Iwabuchi Great Kannon, the 800-year-old spiritual heart of the community.

- Koyama Brewery: Locate the post town monument and discern the "liquid heritage" of the oldest local enterprise.

- Akabane Nature Observation Park: Conclude your walk in the "Healing Oasis" built upon the former army arsenal.

Recommended Nearby

- Historical Hospitality: Explore the traditional storefronts along the old Nikko Onari Kaido path.

- Industrial Tours: Seek out riverfront walks that highlight the industrial transition of the Arakawa or the unique sake-making traditions sustained by the Chichibu groundwater.# Akabane-Iwabuchi: Walking Through a Millennium of Water, War, and Resilience in Northern Tokyo

Reference

- 岩淵宿(いわぶちしゆく)とは? 意味や使い方 - コトバンク, accessed October 13, 2025

- 東海道お菓子旅・常盤貴子さんゆかりの常盤家住宅と間の宿岩淵の栗の粉餅, accessed October 13, 2025

- 荒川放水路と岩淵水門 - 国土交通省, accessed October 13, 2025

- 岩淵水門 - 関東地方整備局, accessed October 13, 2025

- 穴場発見!赤羽の隠れた名所とおすすめスポット - ともトラべライフ, accessed October 13, 2025

- Ekitan 赤羽八幡神社accessed October 13, 2025

- 日光御成道岩淵宿, accessed October 13, 2025

- 小山本家の歴史, accessed October 13, 2025

- 大観音が見守る赤羽岩淵の古刹『正光寺』|さんたつ by 散歩の達人, accessed October 13, 2025

- 第31回 昨日今日明日変わり行く轍軍都物語in赤羽~愉快なロンロン麺 - まぼろしチャンネル, accessed October 13, 2025