(ENG) Beyond the Plum Blossoms: 5 Hidden Gems That Reveal the True Soul of Mito, Japan

We felt the timeless pulse of legacy and life at Rokujizo-ji Temple and uncovered the stark realities of social structure hidden beneath the Mito Castle gate. Finally, we tasted the wisdom of survival embedded in its local cuisine.

常陸第三宮吉田神社 Hitachidaisannomiya Yoshida Shrine > 水戶城大手門 Mito Castle Ote Gate

Listen attentively to the historical stories told in detail

For most, the city of Mito, Japan, evokes a distinct and elegant image: the sprawling Kairakuen Garden, blanketed in the soft pinks and whites of its famous plum blossoms, and the enduring legend of Mito Komon, the wandering vice-shogun immortalized in popular culture. This is the Mito of postcards and period dramas—a city of refined beauty and noble heroes. But what if this familiar facade conceals a far more complex and compelling story?

Beneath the surface of its celebrated landmarks lies a city forged in the crucible of intellectual ambition, rooted in ancient myths, and shaped by a profound wisdom of survival. The true character of Mito isn't just found in its gardens, but in the silent halls of a samurai school, the shade of a thousand-year-old tree, and the subtle flavors of its regional cuisine. This journey unveils five hidden gems, each offering a profound narrative that peels back the layers of history to reveal a more intricate and rewarding understanding of Mito's soul.

The Ideological Forge: Kodokan, The Samurai School of Thought

Long before it was admired for its plum blossoms, the Kodokan stood as the intellectual epicenter of the Mito domain. More than just a school, this was the largest clan academy of the Edo period, a formidable institution where the philosophical currents that would eventually reshape the entire nation were forged. To see it merely as a historic building is to miss its role as the crucible of an ideology that would both build and challenge a new Japan.

The school's founding philosophy was a direct reflection of its creator, the 9th lord of Mito, Nariaki Tokugawa. He envisioned a new generation of samurai skilled in bunbu-ryodo, a philosophy demanding that the sword and the pen be wielded with equal mastery. The Kodokan's very architecture embodies this rigorous ideal. Imagine the scent of old wood in the lecture halls mingling with the metallic tang of sweat from the martial arts dojo—all deliberately placed under one roof to create a unified space where knowledge and action were inseparable. It was conceived not just as a center for learning, but as a deliberately crafted "ideological arsenal," designed to cultivate a warrior class with unparalleled intellectual and physical prowess.

At the heart of its curriculum was Mitogaku, a powerful school of Confucian thought. Herein lies the central paradox of the Kodokan: it was simultaneously a cradle of national rebirth and a forge for an ideology that would later prove tragically rigid. This philosophy provided the "spiritual kindling" for the Meiji Restoration, offering a theoretical framework that would lead to the end of the shogunate. Yet, the same ideas also contained elements that, decades later, were argued to have contributed to Japan’s path toward militarism.

"When knowledge is given an extreme political mission, where do its ethical boundaries lie?"

This silent question echoes through the halls. But the samurai mind, forged in the Kodokan's rigid logic, did not exist in a vacuum. To understand its foundations, one must journey to a place where logic yields to a much older force: the cyclical pulse of life and death, embodied by the ancient Rokujizo-ji Temple.

The Ancient Pulse of Life: Rokujizo-ji Temple's Enduring Cherry Tree

Established in 807 AD, Rokujizo-ji is the oldest temple in the Mito region, a place where history is measured not in decades, but in centuries. Its importance, however, lies in a masterful synthesis: the deliberate merging of the Tokugawa clan's political power with the ancient, local beliefs about life, birth, and lineage that had permeated the land for a millennium.

The temple holds a fascinating dual identity. On one hand, it is an ancient Buddhist site, renowned for bestowing blessings on newborns and ensuring the healthy growth of children. On the other, it serves as the official ancestral shrine of the powerful Mito Tokugawa family. This was a shrewd political move, allowing the ruling clan to legitimize their authority by grafting their lineage onto a deeply rooted spiritual center, effectively borrowing its ancient sanctity to consecrate their modern power.

This connection between clan legacy and timeless life force is beautifully symbolized by a magnificent 200-year-old weeping cherry tree on the temple grounds. Legend holds that this tree is a direct descendant of one admired by Tokugawa Mitsukuni, the famed "Mito Komon." This is more than a charming anecdote; it is a profound metaphor for the cycle of life and cultural continuity, where generations are linked not by stone monuments, but by a living, breathing organism. To stand beneath its branches is to feel the weight of two centuries—a palpable stillness where the rustle of leaves seems to carry echoes of prayers for children long since grown.

This experience of "temporal thickness" is deepened by the presence of thousand-year-old cedar and ginkgo trees. Here, ancient prayers for new life blend with the enduring legacy of a powerful clan, a story of deep-rooted lineage that connects us to the even older, mythological foundations of the land itself.

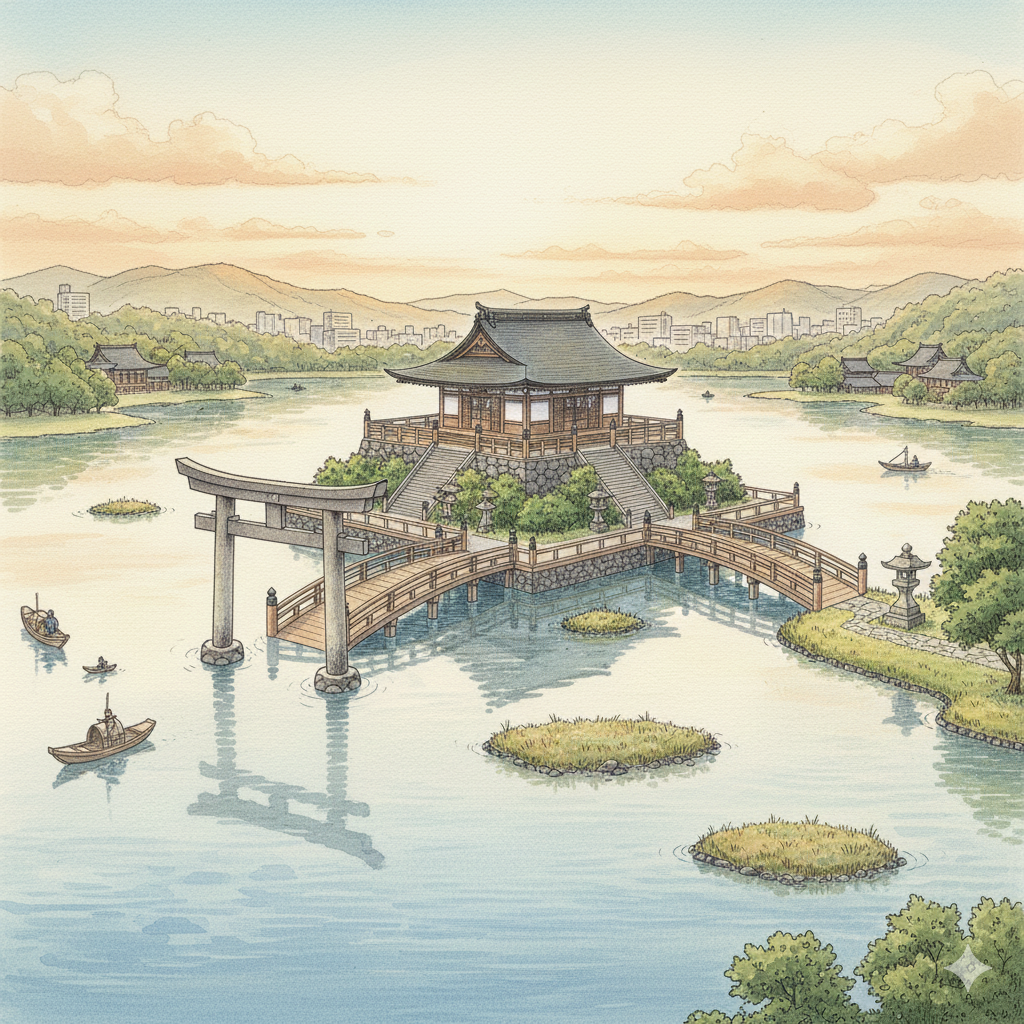

The Mythic Echo: Yoshida Shrine and the City's Primordial Soul

If the Kodokan represents Mito's structured, intellectual mind, then Yoshida Shrine represents its ancient, spiritual soul. As the oldest shrine in the city, its history predates the samurai era, connecting Mito not to political history, but to the foundational myths of Japan. It offers a crucial glimpse into a "pre-civilization" dimension of the city, a layer of primordial forces upon which all subsequent history was built.

The shrine is dedicated to Yamato Takeru, a legendary hero from Japanese mythology whose tales are woven into the very fabric of the Kanto region. By enshrining this mythic figure, Yoshida Shrine anchors Mito in a time of gods and heroes, offering a narrative depth that transcends the more commonly told stories of shoguns and samurai. It reminds us that before Mito was a castle town, it was a landscape alive with myth.

This connection to a primordial past is reinforced by a local legend that the shrine was once situated on a lake. While mythic, this story resonates with the historical reality of Mito's geography as a region rich with rivers and wetlands. This collective memory of a watery landscape is not just a myth; it is a flavor that can still be tasted in the city's culinary history, which begins with the bounty of the eel. The legend serves as an echo of the land's transformation from a wild, watery expanse to a structured urban center.

Today, this ancient site remains vibrantly alive. Worshippers visit to pray for distinctly modern concerns, from finding a partner (en-musubi) to ensuring traffic safety. This seamless blend of the ancient and the contemporary is a testament to the adaptability of belief, demonstrating how primordial myths can evolve to provide comfort and meaning. From this mythical landscape, we now turn to the highly structured, man-made city that was built upon it.

The City of Layers: Mito Castle's Grand Gate and Buried Truths

The magnificent, reconstructed Otemon Gate of Mito Castle stands as a powerful symbol of feudal authority—the grand, public "face" of the domain. Yet, the true hidden gem of this site is not the gate itself, but the stark contrast it presents with the fragmented reality of samurai life buried just beneath the surface of the modern city. Here, history reveals itself in layers, inviting us to look past the official facade to discover a more intimate truth.

The experience can be understood through the metaphor of a garment's "face" (omote) versus its "lining" (uraza). The Otemon Gate is the city's starched collar, presented to the world with immaculate confidence. But it is in the frayed lining—the faint stitches of drainage ditches and the worn fabric of foundation stones—that one can truly feel the texture of daily samurai life. Excavations have revealed these humble fragments of samurai residences, telling a far different story than the monumental gate.

These archaeological remains are critical evidence of the strictly planned and class-divided nature of the Edo-period castle town. They offer a more authentic glimpse into the daily lives and social structure of the samurai than any grand reconstruction ever could. This rigidly planned urban layout is the physical manifestation of the same hierarchical, ordered worldview taught within the nearby Kodokan walls. The philosophy was not just an idea; it was a blueprint for the very ground they walked on.

When you stand before the Otemon Gate, you feel the intended awe. But the real discovery begins when you turn away from it and walk the modern streets, knowing that just inches beneath your feet lie the buried truths of the samurai class. It is a journey from the public face of power to the private, buried truths of everyday life, a story that continues in the intangible yet equally revealing realm of the region's food.

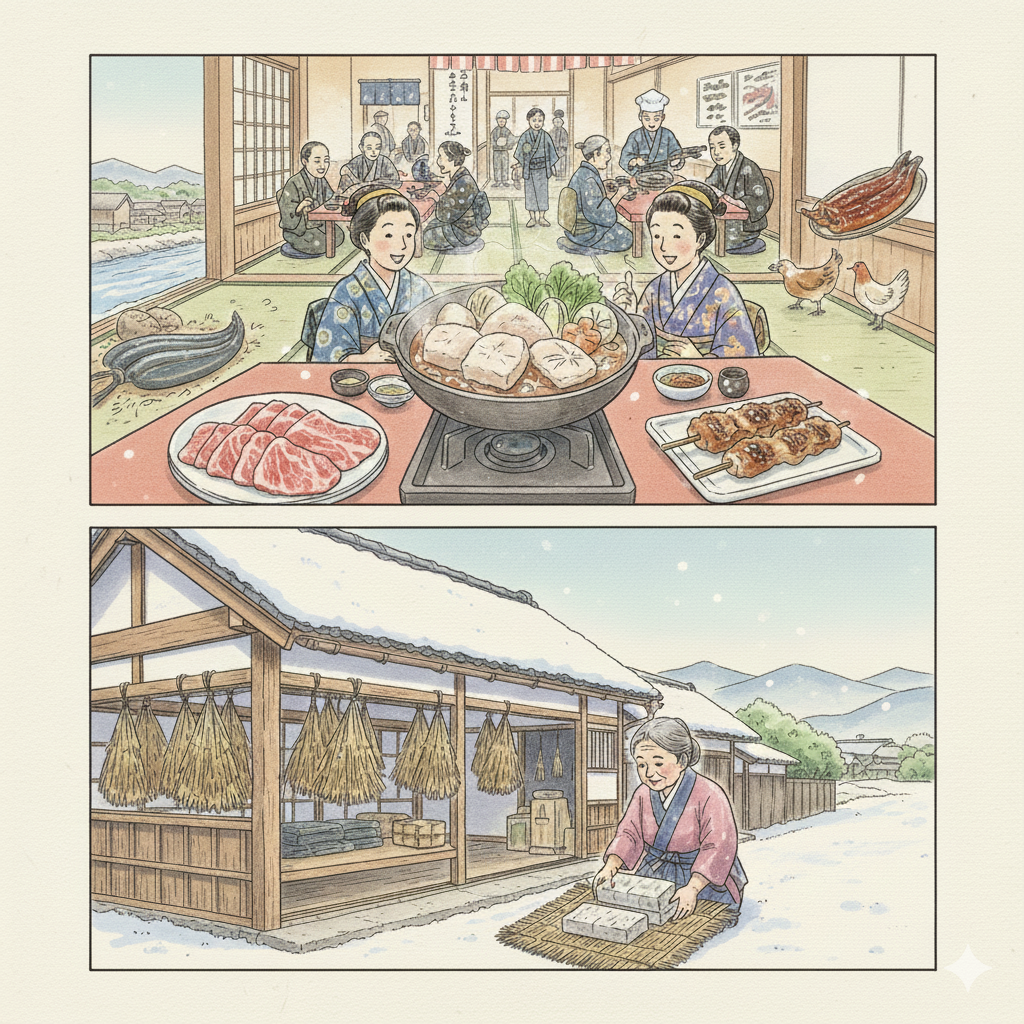

A Taste of History: The Culinary Wisdom Beyond Natto

Mito’s local cuisine is a living historical document, a narrative told through flavor and ingredients. While the city is famous for its fermented soybeans, natto, the region's true culinary story is far richer, revealing a history of geographical change, economic shifts, and a profound wisdom of survival. To eat in Mito is to taste its past.

This culinary story is defined by a compelling duality, reflecting two distinct eras and environments:

- The Cuisine of Abundance: Historically, Mito was a region blessed with abundant water resources. This environment made it a renowned producer of luxurious eel (unagi), a prized delicacy symbolizing the area's natural wealth. This tradition of premium ingredients continues today with Hitachi beef and Okukuji Shamo chicken, representing a legacy of natural bounty.

- The Cuisine of Resilience: In stark contrast, other local foods embody a pragmatic rigor born from the need to endure harsh conditions. The winter specialty Anglerfish hot pot (Anko Nabe) is a testament to adapting to the cold. Preserved foods like frozen konjac (Shimi Konnyaku), made by using the winter climate for freeze-drying, and Soboro Natto, which combines natto with dried radish, speak to a philosophy of thrift, preservation, and making the most of every resource.

This duality in the local diet—from the luxury of eel to the ingenuity of preserved foods—mirrors the region's history. It tells a story of a changing relationship with the environment and the evolution of a community's philosophy of endurance. Eating in Mito is not just a sensory experience; it is a way of tasting the city's economic history. These five stories, from philosophy to food, combine to paint a complete portrait of the city.

The Five Senses of a Deeper Mito

Our journey through Mito’s hidden gems reveals a city far more profound than its famous plum blossoms suggest. We have traveled from the disciplined intellect of the Kodokan, where ideas that shaped a nation were born, to the mythic spirit of Yoshida Shrine, which connects the city to its primordial origins. We felt the timeless pulse of legacy and life at Rokujizo-ji Temple and uncovered the stark realities of social structure hidden beneath the Mito Castle gate. Finally, we tasted the wisdom of survival embedded in its local cuisine.

The true value of visiting Mito, therefore, lies not just in seeing its sights, but in experiencing this "philosophical journey" through its hidden layers. By looking beyond the familiar, we discover a city that engages all the senses and invites deep reflection. It leaves us with a question that resonates far beyond the borders of Mito itself.

What hidden stories are waiting to be discovered in the places we think we already know?

Works Cited

- Hsu Chieh, Ryoko-zu. "[Mito Attractions | Mito Han School Kodokan: More Than Just Plum Blossoms! Explore the Largest Han School in Japan and the Path of Edo's Literary and Martial Arts]".

- QQ News. "[Mito School: How the Ideas of a Great Ming Confucian Enlightened the 'Showa' Men? | Xunji Xiaojiang]".

- IBARAKI GUIDE. "[Mito Daishi Rokujizo-ji Temple | Visit]".

- AVA Travel. "[Rokujizo-ji Temple (Mito Daishi) | Sightseeing Spots in Mito]".

- Roundtrip JP. "[Hitachi Daisan-no-miya Yoshida Shrine, a Famous Spot for Cherry Blossoms in Mito!]".

- AVA Intelligence. "[Hitachi Daisan-no-miya Yoshida Shrine | Sightseeing Spots in Mito]".

- Mito Tourism and Convention Association. "[Lots of Local Gourmet: The 'Taste' of Mito]".

- Mito Tourism and Convention Association. "[Mito Castle Otemon Gate]".

- National Comprehensive Database of Cultural Properties. "[Mito Castle Ruins (112th Survey)]".

- Mito City Official Website. "[Let's Convey Washoku Culture (Health Promotion Division)]".