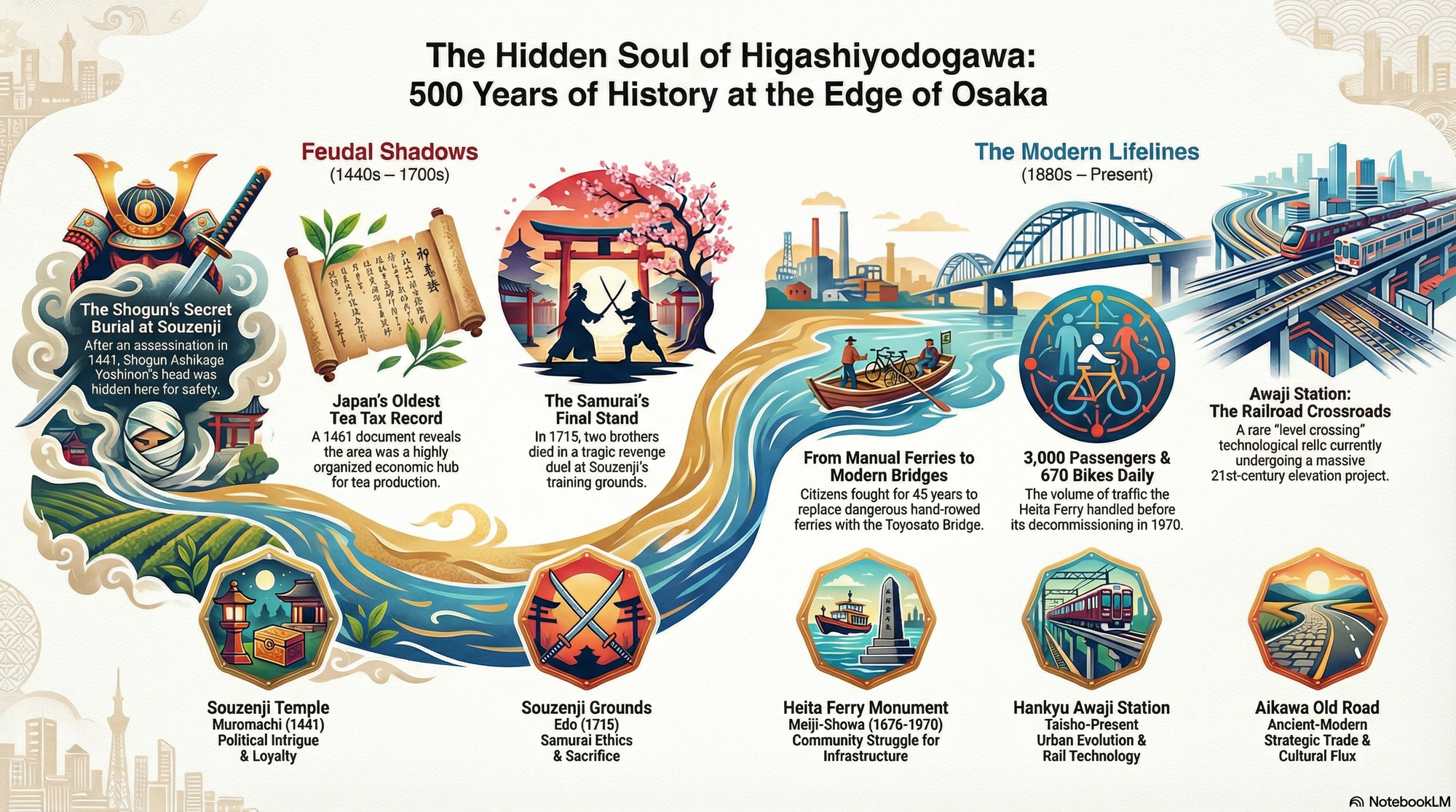

(ENG) Higashiyodogawa Ward: Five Histories That Shaped Osaka's Forgotten Frontier

Higashiyodogawa's significance lies in its identity as a "borderland" where the city’s most extreme historical events took place.

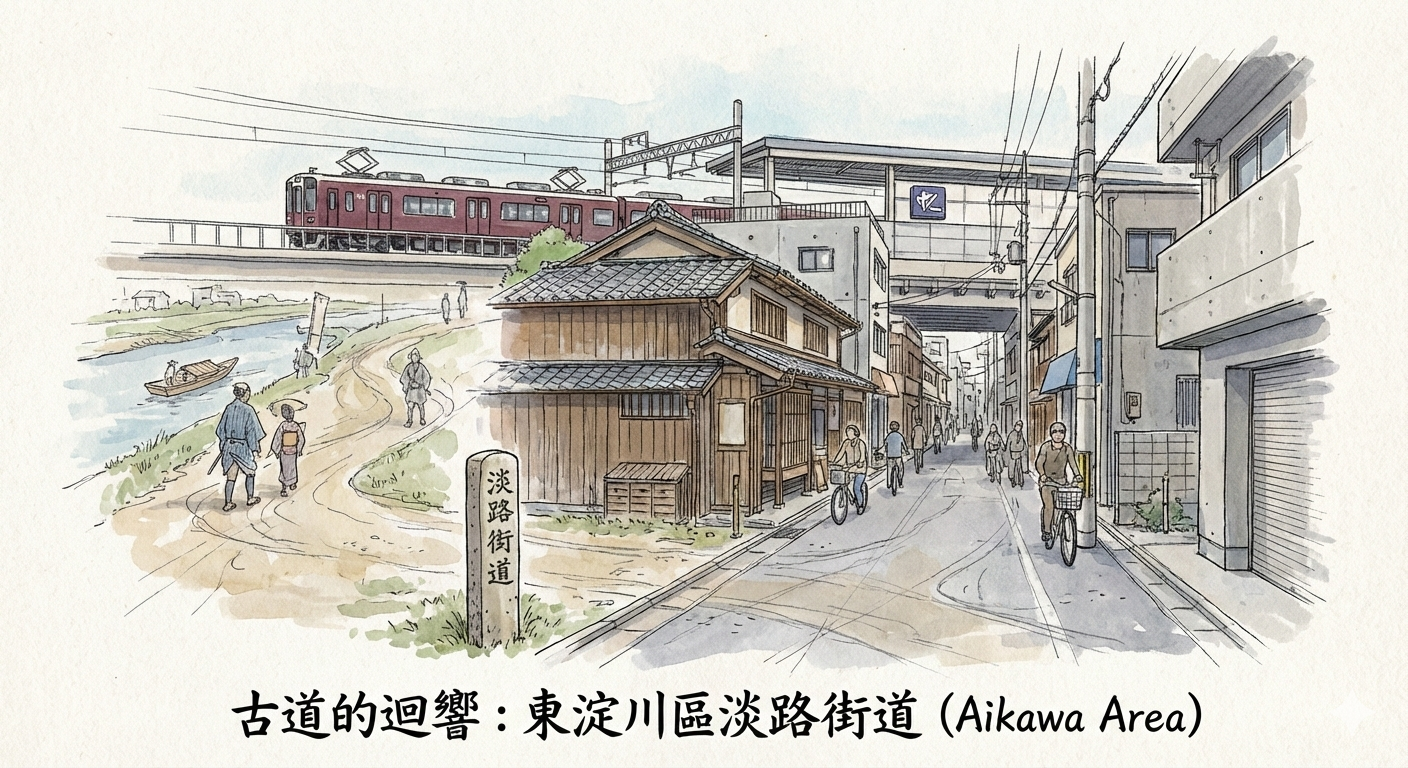

足利義教公首塚 the head mound of Ashikaga Yoshinori > 淡路街道 十字路口 the Awaji Kaidō

Listen to the historical stories told in detail (For subscribers only)

The City You Walk Past Every Day

Walk the streets of Higashiyodogawa Ward today, and you’ll find unassuming apartments and the ceaseless hum of commuter trains. But beneath this modern surface lies a forgotten frontier. Situated north of the Yodo River, this area was historically known as "Nakajima," a strategic borderland defined by the waterways that made it a crucial crossroads between the ancient capital of Kyoto and the commercial heart of Osaka. While the grand castles and temples of the city center draw the crowds, it was here, on the periphery, that some of Japanese history’s most dramatic and consequential chapters were written. This is not a history of monuments, but of moments—of secret burials, bloody duels, and daily struggles. This guide invites you to walk these streets and uncover the hidden stories that reveal how the fate of shoguns and the lives of commoners were decided on this overlooked landscape.

The Shogun's Head: A Political Secret Buried in Sōzen-ji Temple

In feudal Japan, the body of a ruler was more than mere flesh; it was a potent symbol of legitimacy and power. To possess the remains of a leader was to control the narrative of their reign and the right to succession. In the turbulent 15th century, the secret handling of a shogun’s head was not just a matter of honor, but an act of supreme political consequence that could steady a teetering regime.

The year was 1441, a time of political turmoil that culminated in the Kakitsu Incident: the brutal assassination of the tyrannical 6th Shogun, Ashikaga Yoshinori. In the chaotic aftermath, with enemy forces eager to seize the shogun’s head as a trophy to shatter the authority of the Ashikaga shogunate, one loyal retainer took decisive action. Hosokawa Mochitsune, a close confidant of the shogun, covertly smuggled the head from the scene of the murder. He needed a secure, secret location for a dignified burial, far from the prying eyes of the capital but close enough for loyalists to protect. The remote, river-bound region of "Nakajima"—modern Higashiyodogawa—was the perfect choice. Its strategic isolation provided the necessary secrecy for this high-stakes political act.

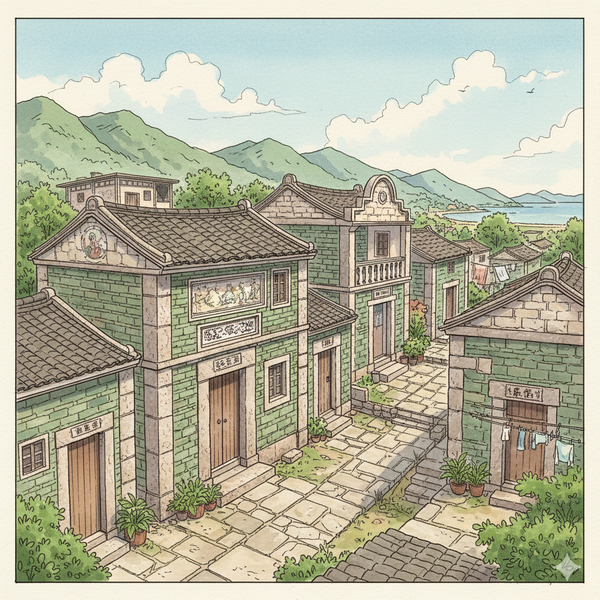

The following year, Hosokawa Mochitsune founded Sōzen-ji Temple (崇禪寺) on the site of the secret burial. This was far more than a religious gesture; it was an act of political consecration, transforming a secret burial ground into a permanent statement of loyalty written in timber and stone. Centuries later, a document discovered at the temple would shatter the stereotype of this "remote" area being a barren frontier. The cha-nengu-mokuroku, a record of tea taxes paid to the temple, was found to be the oldest in Japan. This small record proves the existence of a sophisticated, well-administered economy capable of bankrolling the political maneuvers of major clans. It reveals why this place was chosen: it was a region mature enough to support and conceal one of the most sensitive political secrets of the era.

How to Experience It Today

To find this 500-year-old secret, pass through the temple's main gate and make your way to the quiet hillock rising behind the main hall. It is unassuming, marked only by stone and moss, but this is the place: the head mound of Ashikaga Yoshinori (足利義教公首塚). Stand before this simple earthen tomb and contemplate the weight of an act of loyalty on a forgotten frontier that preserved the dignity of a shogun and shaped the fate of a nation.

This hallowed ground, consecrated by a shogun's secret, would later be stained by the blood of samurai. But beyond these elite dramas, a different struggle was unfolding daily on the banks of the great river that defined this borderland.

The Bloody Horse Grounds: An Edo-Period Samurai Tragedy

During the relative peace of the Edo period, the age of civil war had passed, but the samurai code of honor remained deeply ingrained. The principle of katakiuchi (仇討), or honorable revenge, was a solemn duty that could compel a warrior to violence to restore a family’s name, turning quiet suburban fields into deadly dueling grounds.

This story centers on the Enjō brothers, samurai from the Yamato-Kōriyama domain. Their world was shattered when their younger brother, Sōzaemon, was dishonorably killed. He had previously bested a man named Ikuta Denpachirō in a fair duel, but Denpachirō, unable to accept defeat, resorted to a cowardly night attack (闇討ち). For the Enjō brothers, this was an unforgivable stain on their family’s honor. Bound by the warrior’s code, they swore revenge.

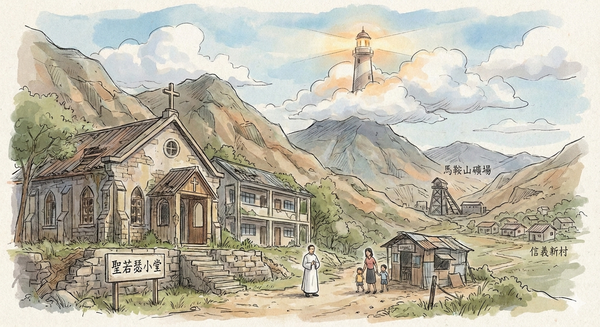

The final confrontation took place on November 4, 1715, at the Sōzen-ji horse grounds (崇禪寺馬場), an open area on the temple lands used for martial training. But their quest for honorable revenge was met with treachery. Ikuta Denpachirō had assembled a large group of his own followers. Hopelessly outnumbered, the Enjō brothers fought valiantly but were ultimately cut down in what became a kaeri-uchi—a "revenge-killing-in-reverse."

The brutal outcome of the duel resonated deeply with the local community. Moved by the brothers' adherence to the code of honor, even in death, the head priest of Sōzen-ji and a former police official named Katsumi Muneharu erected a tomb to honor their spirits. This act reveals a profound local respect for the ideals of samurai loyalty and sacrifice, recognizing the nobility of the brothers' cause despite the bloody result of their private war.

How to Experience It Today

Within the grounds of Sōzen-ji Temple, seek out the Grave of the Enjō Brothers (遠城兄弟之墓). The horse grounds themselves have long since vanished, but this stone monument serves as a powerful focal point. Standing before it, you can easily imagine the crisp autumn air of 1715, the clash of steel, and the final moments of a tragic samurai drama played out far from the battlefield.

From the high drama of the samurai class, our story now shifts to the daily struggles and quiet triumphs of the common people whose lives were shaped by the great Yodo River.

The Last Ferry: A Community's Lifeline Across the Yodo River

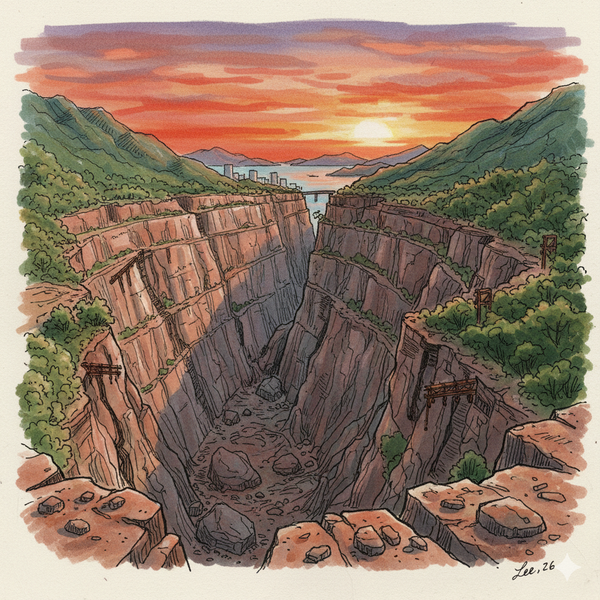

For centuries, the great Yodo River was both the lifeblood and the tyrant of the villages that would become Higashiyodogawa. This is the story of the community's last stand against that tyranny: a single, hand-powered boat.

The Heita-watashi (平田渡) ferry began service around 1676, a humble boat connecting villages across the Yodo. Its importance magnified dramatically after the great Meiji-era rerouting of the river, a massive flood-control project that physically cut communities like Toyosato Village off from the south bank. Suddenly, the ferry was no longer a convenience but an essential lifeline.

For decades, life revolved around the slow, hand-powered boat. Schoolchildren depended on it daily, and a journey that takes minutes today could involve twenty minutes of strenuous rowing, with frequent cancellations due to bad weather. The community’s persistent demand for better access drove a slow but steady evolution, a powerful story of a community successfully fighting for public infrastructure rights. The ferry went from a private business to village-run, then to publicly operated, and finally, in 1919, was legally designated as a public road (東淀川區386號), making it free for all. Even in its final years, after being upgraded to an engine-powered vessel, the ferry carried an astonishing 3,000 people and 670 bicycles across the river every day.

The community’s dream of a permanent crossing, a dream held for nearly 45 years, was finally realized on March 3, 1970, with the opening of the Toyosato Bridge (豐里大橋). On that day, the Heita-watashi made its final journey, marking the end of the very last public ferry service on the Yodo River. Its closure was not an ending but the culmination of a generations-long struggle for modernization and connection.

How to Experience It Today

Walk across the modern Toyosato Bridge and pause midway. On the riverbanks below—on both the Higashiyodogawa side and the opposite Asahi ward side—you will find the Heita-watashi memorial stones (平田渡紀念碑). Look closely and you'll reward your observant eye with a discovery: the subtle difference in the Japanese script on the two monuments, with one using "平太渡し" and the other "平田渡し." As you watch the traffic hum across the bridge, imagine the river below filled not with concrete pillars, but with the quiet determination of a single boat pulling a community together, one crossing at a time.

This story of overcoming the river that defined the area's ancient geography gives way to the story of the railways that would forge its modern identity.

The Railway Maze: Awaji Station's Ground-Level Spectacle

In the early 20th century, private railway companies radically reshaped the Japanese landscape. They didn't simply build tracks to connect existing towns; they often built tracks into open fields and, in doing so, created new urban centers from scratch. Awaji Station is a perfect, living monument to this transformative era.

When Awaji Station (淡路駅) opened in 1921, it was little more than a junction in the countryside. Its importance was purely strategic: it was the point where two major private commuter lines, the Hankyu Kyoto Main Line and the Senri Line, were destined to meet. This junction became the gravitational center around which modern Higashiyodogawa would grow, transforming the area from a collection of riverside villages into a quintessential railway-driven suburb.

For nearly a century, Awaji Station has been famous among railway enthusiasts for a feature that is exceptionally rare in modern Japan: a ground-level flat intersection. Here, two of the busiest commuter lines in the Kansai region cross each other at the same grade. This design, a product of early 20th-century cost and engineering constraints, became both a notorious operational bottleneck and a celebrated spectacle. Now, that is coming to an end.

A colossal work of concrete and steel, the track elevation project (立体交差), is slowly erasing a century of railway history from the sky. This massive undertaking represents the inevitable victory of modern efficiency over a fascinating but obsolete piece of industrial heritage, and its completion will close a chapter on the city's past.

How to Experience It Today

Visit Awaji Station before the elevation project is complete. Stand on the platform and witness the unique spectacle of the ground-level crossing for yourself—the carefully choreographed dance of steel that has defined this spot for a hundred years. Then, look up at the massive structures rising above. You are witnessing a rare moment: a living piece of railway history at the precise instant of its transformation into a memory.

From the modern steel of the railways, we now journey further back in time, to the ancient dirt paths that first established this area as a critical corridor.

The Ancient Highway: Tracing Faint Footsteps on the Awaji Kaidō

What ghosts lie buried beneath the asphalt you walk on every day? In Higashiyodogawa, the answer is an ancient highway that once carried armies and merchants, and whose path still dictates the flow of the city.

Long before railways, the area known as "Nakajima" was bisected by the Awaji Kaidō (淡路街道), a strategic highway connecting major political and commercial centers. This road was the physical artery that made the region’s sophisticated economy possible, the very economy evidenced by the 15th-century tea tax record at Sōzen-ji. It was this constant flow of goods and people that established the area's fundamental identity as a natural crossroads.

This historical role as a transit hub has never faded; it has only evolved. The foot traffic of medieval merchants has been replaced by the commuter flows of modern trains. The modern railway is simply the 20th-century manifestation of the same strategic transit corridor the Kaidō established centuries earlier. The very name of a local station like Aikawa (相川駅), which can be interpreted as "converging rivers," echoes the area's deep and enduring relationship with geography and transport. The ancient highway and the modern railway are two expressions of the same timeless purpose.

How to Experience It Today

This final piece of history isn't found at a single monument. Instead, walk the streets around Awaji and Aikawa stations. Don't look for a plaque; look for the logic of the landscape. As you navigate the grid, imagine the faint echo of the Awaji Kaidō beneath your feet. Feel the overlap of centuries, where the path of a medieval traveler and a modern commuter occupy the same essential space, defined by the unchanging need to move from one place to another.

These five stories, from a shogun's secret to a commuter's path, all converge to reveal the unique character of this borderland.

The Power of the Periphery

Higashiyodogawa's history is powerful precisely because it is a history of the periphery. Its true significance lies in its identity as a "borderland" where the city’s most extreme historical events took place. It was because it was secluded on the edge of political power that it became the only safe place to bury a shogun’s head. It was because it offered space away from the city that a brutal samurai duel could unfold. And it was because a river stood in their way that a community fought for decades to build a bridge, driving the very modernization of the city.

The area's overlooked status has given it a hidden authenticity. This teaches us that the most authentic history is often found not in the grand, central monuments designed to be remembered, but in the marginal spaces where life, and death, truly happened. The character of a city is forged as much by its edges as by its center.

True travel is about finding the places that weren't meant to be remembered, but are impossible to forget. It’s in these borderlands—on the banks of a forgotten ferry crossing or beneath the shadow of a rising railway—that a city's real story is told.

What hidden histories lie waiting in the quiet neighborhoods you pass through every day?

Further Reading and Engagement

- Read more in our complete historical travel guide to Osaka.

For more stories that uncover the hidden layers of the world, consider subscribing to our newsletter.

Reference

- 凌雲山 崇禅寺【大阪市東淀川区】霊園/墓地/霊苑/曹洞宗/足利義教の ..., 檢索日期:10月 11, 2025

- 崇禅寺の歴史 - 曹洞宗 凌雲山 崇禅寺(そうぜんじ) - Ameba Ownd, 檢索日期:10月 11, 2025

- 平田渡し-淀川の渡し船--地域のお宝さがし-69|植松清志 - note, 檢索日期:10月 11, 2025

- 徳島河川国道事務所-阿波歴史街道, 檢索日期:10月 11, 2025

- タイトル 投稿者 いつ頃 思い出 場所 補足・追加情報 参考文献 受付日 利用条件 区名 年代 分野 - 大阪市立図書館, 檢索日期:10月 11, 2025

- 相川駅 (阪急京都本線) - 大阪市東淀川区相川/駅 - マップ, 檢索日期:10月 11, 2025