(ENG) Osaka's Forgotten Heart: 5 Histories Hidden in Plain Sight

The hidden gems of Nishi Ward are not grand monuments, but profound connections that reveal how this unassuming district was a crucible where the economic, intellectual, and cultural forces of modern Japan were forged.

京町堀 Kyomachibori > 日本聖公會大阪主教座聖堂 The Kawaguchi Christ Church

Listen attentively to the historical stories told in detail

Beyond the Bright Lights

When we picture Osaka, our minds fill with images of Dotonbori’s electric glow, the aroma of street food sizzling on a grill, and a current of irrepressible energy. It’s a city that pulses with a vibrant, forward-looking spirit. But what happens when you step away from the main thoroughfares into a district like Nishi Ward, with its orderly grid of modern streets and business towers? The surface suggests a history erased, a place rebuilt for pure function and efficiency.

But what if that very orderliness is itself a scar, a clue to a story of profound devastation and rebirth? What if beneath the calm surface of a park or the quiet hum of a wholesale district, the foundational stories of modern Japan are waiting to be discovered?

This journey ventures beyond the bright lights to uncover five surprising histories hidden in plain sight within Osaka’s Nishi Ward. Each story reveals another layer of a city built not just on commerce, but on an incredible capacity for resilience, adaptation, and transformation—a profound narrative of a forgotten heart that still beats strong.

The Ghost of a Global Port: Where Osaka First Met the World

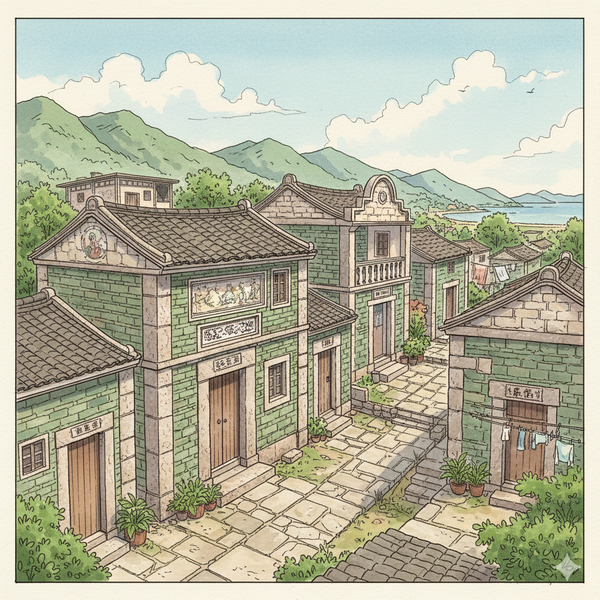

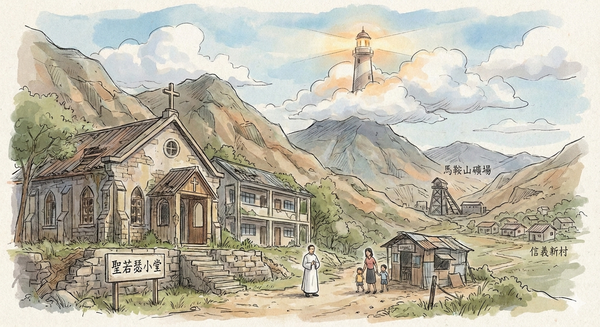

Long before the Shinkansen and international airports, Osaka’s gateway to the world was a small, bustling enclave on the banks of the Kitsu River. The Kawaguchi Foreign Settlement, established in 1868 at the dawn of the Meiji Restoration, was a radical experiment—the city’s first-ever international window, where Japan’s feudal past collided head-on with the industrializing West.

For a brief, dazzling moment, Kawaguchi was a vision of the future. Companies from Britain, France, Germany, and the United States set up offices. European-style buildings lined neatly planned, tree-lined avenues where sidewalks were separated from the roads, and the nights were illuminated by the soft glow of kerosene gaslights. This was where Osaka tasted its first Western-style bread and where the city's first European restaurants opened their doors, serving a clientele of foreign merchants and curious locals.

But the dream was short-lived. The port’s shallow waters couldn’t accommodate the larger steamships of the era, and global trade quickly migrated to the naturally deep harbor of nearby Kobe. As Westerners departed, however, a new international chapter began. Chinese immigrants, primarily from Shandong province, moved in. By the early Showa period, this was no small enclave; it was a significant hub for around 3,000 overseas Chinese, even hosting the Osaka branch of the Republic of China’s consulate. This rapid pivot—from a failed Western trading post to a thriving diplomatic and social center for the Chinese community—was one of Osaka's first critical lessons in urban adaptability.

Today, the foreign consulates and trading houses are long gone, but one magnificent remnant stands as a testament to that era. The Kawaguchi Christ Church, a Gothic red-brick cathedral completed in 1920, remains a stunning hidden gem. Its elegant spires and arched windows are a physical monument to Osaka’s first, tentative steps onto the global stage, a beautiful ghost of a dream that sparked the city’s modern identity. While this international experiment was fleeting, other parts of the ward were about to undergo even more radical transformations, forged in the crucible of war and peace.

The Airstrip in the Rose Garden: Utsubo Park's Secret Military Past

Utsubo Park is a beloved green oasis in the heart of Osaka, a place of rose gardens, tennis courts, and quiet relaxation. Yet its very shape—a peculiar, narrow rectangle stretching 800 meters long but only 150 meters wide—is a historical scar that tells an incredible story of urban reinvention. This peaceful park is a piece of land that has lived three distinct lives: as a center of commerce, a tool of war, and finally, a symbol of peace.

Its story begins in the Edo period, when this land was home to the Zakoba fish market, the largest and most raucous in all of Osaka. It was the engine of the "Nation's Kitchen," where the air was thick with the cries of fishmongers.

"安い!安い!" (Yasui! Yasui! / Cheap! Cheap!)

According to a cherished local legend, the great 16th-century leader Toyotomi Hideyoshi, upon hearing these cries, gave the area its name. As a pun on the cry "Yasui," he called the place "Yasu" (arrow nest), which in turn became "Utsubo"—the Japanese word for an arrow quiver.

This centuries-old commercial hub was completely obliterated during World War II. In the aftermath, the U.S. military repurposed the flattened, empty space for a far different purpose: it became a military airstrip. The park's unique, runway-like dimensions are a direct legacy of this occupation-era history. This extreme functional shift reveals a core principle of Osaka's resilience: a concept historians call "functional succession." The land never lost its purpose as a crucial "circulation node"—first for goods, then for military transport, and finally for the public. The city did not just rebuild; it fundamentally reimagined the very purpose of its urban spaces.

From this history, a new form of commerce has bloomed. On the park's northern edge lies Kyomachibori, one of Osaka’s most sophisticated modern neighborhoods. Its chic cafes, artisan bakeries, and high-end design shops are the modern evolution of the area's commercial spirit. The blue-collar energy of the old fish market has been transformed into a hub of white-collar aestheticism, proving that even after centuries and cataclysms, the land's commercial soul endures. The economic power once concentrated here, however, was just one facet of the immense wealth flowing through Nishi Ward.

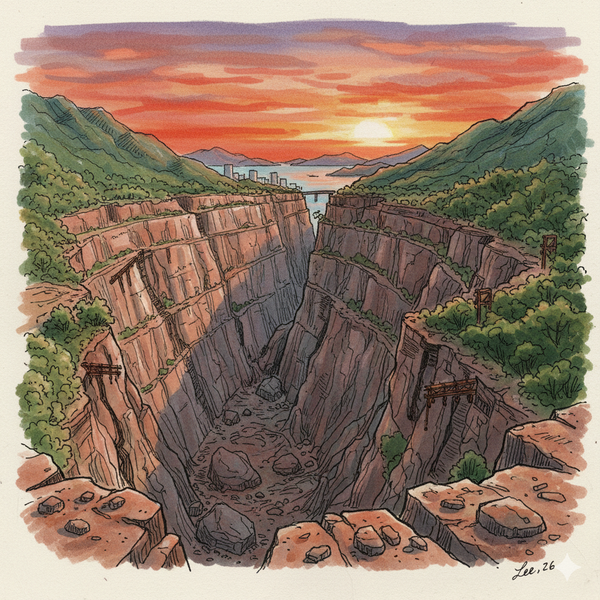

The Financiers of a Revolution: How a Warehouse District Shaped Modern Japan

During the Edo period, Osaka was famously known as the "Nation's Kitchen," the undisputed economic engine of Japan. The heart of this engine was in Nishi Ward, where powerful feudal lords established kurayashiki—sprawling warehouse-residences along the canals—to store, sell, and trade goods from their domains. These were not mere storehouses; they were the Wall Street of feudal Japan.

Among the most powerful was the Satsuma Domain. They maintained three warehouses in Nishi Ward: an upper residence in Tosa-bori for political and residential affairs, a middle one, and a lower warehouse in Itachibori dedicated purely to storing goods. As the Edo period waned, these warehouses took on a new, revolutionary purpose: they became the financial backbone of the movement to overthrow the shogunate. The funds raised and managed within these Nishi Ward depots directly financed the military campaign that would ultimately lead to the Meiji Restoration.

While the original buildings were destroyed in the war, the area’s economic DNA has proven remarkably persistent. A walk through Itachibori, the former site of the Satsuma clan's lower warehouse, reveals a district dedicated to wholesale industrial tools, steel, and hardware. The goods have changed from rice and textiles to machinery and metal, but the fundamental purpose of the place as a center for goods and logistics remains the same. To find the stone marker designated as the Osaka City Designated Historic Site: "Satsuma Clan Warehouse Residence Ruins" and then wander through Itachibori is to witness a commercial bloodline that has flowed for centuries, connecting the finances of samurai lords to the supply chains of modern Japan. But while money and goods flowed through these canals, so too did the powerful ideas that would change the nation forever.

The Birthplace of an Uprising: A Scholar's Quiet Influence

History is not only shaped by warriors and merchants but also by thinkers. And in the late Edo period, few minds were more influential than that of Rai Sanyo, a historian and scholar born in Nishi Ward in 1780. His birthplace was no grand estate, but an elegant house of letters, with half the structure protruding over the Edobori canal, offering its residents tranquil views of wisteria and bonsai. It was here that a life dedicated to work that would provide the intellectual spark for a revolution began.

His masterwork, Nihon Gaishi (An Unofficial History of Japan), was a powerful retelling of Japanese history that championed the authority of the Emperor over the shogun. Published in 1827, it became the essential text for the "Revere the Emperor" movement, providing the philosophical justification for the samurai who would eventually topple the shogunate and usher in the Meiji era.

What makes this story so compelling is its location. Rai Sanyo's birthplace—the "brain" of the revolution—was just a short walk from the Satsuma warehouses—its "wallet." This geographical convergence is a potent symbol of Nishi Ward's role as a crucible where revolutionary ideology and the capital required to enact it were forged together. It was a place where both the ideas for a new Japan and the funds to build it were born.

Today, in the shadow of soaring office towers near Higo Bridge, a humble stone marker quietly denotes the Rai Sanyo Birthplace Monument. The true reward for a curious traveler is stumbling upon this quiet marker. In that moment of discovery, you realize you are standing at the intellectual source code of modern Japan, hidden in plain sight amidst the hustle of a modern business district. Alongside finance and intellectualism, Nishi Ward was also the undisputed center of Osaka's vibrant and sophisticated cultural life.

The Echo of the Floating World: From Geishas to Graphic Design

In the Edo period, the Shinmachi district was a world unto itself. As one of Japan's three great licensed pleasure quarters (yūkaku), alongside Kyoto's Shimabara and Edo's Yoshiwara, it was the glittering heart of "Naniwa" culture—a floating world of art, entertainment, and sophisticated luxury. Its northern edge was famously lined with the "Kuken Sakura-zutsumi," the Nine-House Cherry Blossom Embankment, a celebrated scenic spot each spring.

But Shinmachi was far more than a red-light district; it was a cradle for the arts. It was here, in this world of refined entertainment, that one of the greatest Kabuki actors in Japanese history, Ganjiro Nakamura I, was born in 1860. The district was a major patron of theater, music, and design, setting the aesthetic standards for the entire region.

The physical pleasure quarter has long since vanished, with only the Shinmachi Kuken Sakura-zutsumi Ruins monument in a local park to mark its existence. However, its spirit—a deep cultural investment in aesthetics, craftsmanship, and a high-quality lifestyle—has been reborn in a modern form just next door. The neighboring district of Minamihorie, once a traditional area for furniture makers, has evolved into Osaka's premier destination for high-end design boutiques, interior design studios, and chic cafes. This transformation represents a direct lineage. The pursuit of beauty and refined living that once defined Shinmachi now defines Minamihorie. The clientele and the context have changed, but the fundamental appreciation for quality, design, and a sophisticated lifestyle remains. This final story of cultural evolution perfectly encapsulates Nishi Ward's incredible capacity for reinvention.

Reading the Layers of the City

From the global trade that first breached its shores, to the samurai silver that funded a revolution and the scholar's words that justified it, the stories of Nishi Ward weave a single, powerful narrative. The phantom port, the military runway turned park, the revolutionary treasury, and the pleasure quarter reborn as a design hub all prove that the true character of a city is not found only in what is immediately visible, but in the layers of history stacked just beneath its modern streets.

This journey invites us to practice "historical penetrability"—the ability to stand in one reality and sense the echoes of another. It’s the feeling of standing in the quiet green of Utsubo Park and hearing the faint cries of Edo-era fishmongers, or walking past a hardware wholesaler in Itachibori and imagining the flow of samurai silver that once funded a nation's remaking. The hidden gems of Nishi Ward are not grand monuments, but profound connections that reveal how this unassuming district was a crucible where the economic, intellectual, and cultural forces of modern Japan were forged.

The next time you walk through a modern city, what hidden histories might you be standing on?