(ENG) Osaka’s Minato Ward: From Meiji Ambition to Post-War Resilience — An Urban Archaeology Walk

Osaka’s Minato Ward transformed waste into mountain, war-torn ruins into new foundation, and the threat of flooding into a technological shield.

How did engineering projects transform Minato-ku into a cultural landmark?

The significance of the 2-meter ground raising project.

What stories do the historic Red Brick Warehouses tell today?

Listen to the historical stories told in detail (For subscribers only)

To the casual observer, Osaka’s Minato Ward appears as a modern maritime landscape of steel, neon, and glass. Yet, for those who look closer, this district is a masterpiece of human willpower—a landscape where the very earth is an "artificial geography." As a cultural historian, I view this ward not as a natural coastline, but as a palimpsest: a layered document of engineering, sacrifice, and the strategic "Sea Gateway" that fueled Japan's modernization. To walk through Minato is to feel a hundred and fifty years of calculated human intervention beneath one’s feet. The salt-slicked air and the rust-stained industrial relics are not merely remnants; they are the physical markers of a city that has repeatedly reinvented itself from the silt up.

The Mythic Peak: Tenpozan and the Art of Dredging

The narrative of Minato Ward is one of alchemy—the transformation of river-silt into mythic geography. In the 1830s, the dredging of the Anji River produced a staggering byproduct: massive mounds of mud and sand. Rather than treating this as waste, the planners of the Edo era engaged in a brilliant feat of social engineering, sculpting the debris into what is now Mt. Tenpo.

Standing at a humble 4.53 meters, it was branded as a "Naniwa Shin-Meisho" (New Famous Place of Naniwa). By naming the mound after the Tenpo era and linking it to the Chinese "Mount Penglai"—a legendary floating peak carried by a sacred turtle—the city transformed an engineering site into a spiritual destination. It served a dual purpose: while "pleasure-seekers never ceased throughout the four seasons" to enjoy its cherry blossoms and pines, the mountain also housed a kōtōrō (high lantern), a vital navigation mark for ships entering the harbor.

Today’s traveler can trace this history via the "History Pottery Tablets" embedded along the seawalls. These 浮世繪 (Ukiyo-e) scenes, mirroring the works of Hiroshige, offer a striking juxtaposition: the vibrant, woodblock-printed leisure of the 19th century set against the modern silhouette of the Kaiyukan aquarium. It is a reminder that the port’s charm was intentionally manufactured from the very beginning.

The Thirty-Year Dream: Meiji Engineering and Global Synergy

If Tenpozan was a project of leisure, the "Great Port Construction" of 1897 was a national-level manifestation of will. This was a "Thirty-Year Dream" that spanned from the Meiji era to the early Showa period, representing Japan’s existential drive to industrialize. The challenge was immense: a battle against shifting tides and relentless silt that required more than local labor; it required an international knowledge transfer.

The harbor we see today is the result of a collaboration between Dutch engineer Johannes de Rijke—the "father of flood control"—and Japanese pioneers like Nishimura Sutezo and Okino Tadao. De Rijke brought European standards to the Osaka coast, designing the breakwaters and foundations that still dictate the harbor’s flow. For the modern traveler, the harbor is a "hundred-year foundation." The very piers where modern cargo ships dock were dreamed into existence by men working with 19th-century tools and 21st-century vision.

Silent Witnesses: The Red Brick Warehouses of the Taisho Era

By 1923, the completion of the Sumitomo Red Brick Warehouse group marked the zenith of Osaka’s golden age of trade. These structures are the physical imprints of a "heavy industrial aesthetic"—robust, unyielding, and dignified. While the nearby Ferris wheel and aquarium hum with the kinetic, brightly colored energy of tourism, the warehouses stand in a state of "staged preservation."

Currently non-public, these buildings exist in a pocket of frozen time. This lack of access adds a layer of mystery, making them a "hidden gem" for those who prefer the quietude of history to the noise of the present. They represent a pause in the city’s relentless growth, serving as a silent witness to the era when Osaka was the premier trading hub of the Far East.

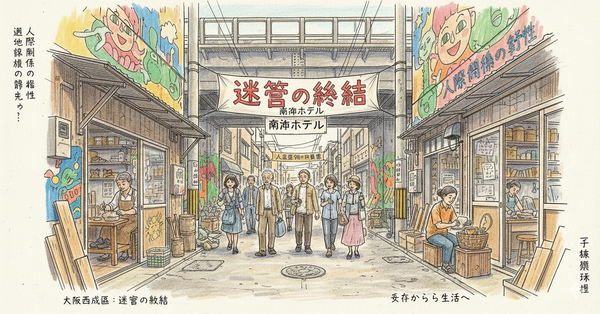

The Sunken First Floor: A Lesson in Collective Resilience

The most poignant layer of Minato Ward’s history is found not in its monuments, but in its houses. Following the devastation of World War II, the district faced a silent catastrophe: land subsidence. Decades of groundwater extraction had caused the earth to sink, leaving the ward at the mercy of the sea. In 1946, the city launched the "Land Readjustment Project," an audacious plan to raise the entire district by two meters using soil dredged from the harbor.

This created the "sunken first floor," a phenomenon unique to neighborhoods like Chikko and Yunagi. As you walk these side streets, you will see older homes where the windows sit at the level of the pavement, and entrances descend into what should have been the ground floor. Look also for the manhole covers; they often remain as markers of the original ground level relative to the raised buildings.

This is urban archaeology in its most human form. These architectural oddities are the physical evidence of a community’s silent commitment to public safety—a collective sacrifice where residents allowed the very earth to rise around their lives to ensure the survival of the neighborhood.

Sentinels of the Tide: The Great Water Gates and the Memorial

The final defense of this man-made landscape was completed in the 1970s. The great seawalls and the 1972 Mema Drainage Pump Station are the "technological fortresses" of Japan’s High Economic Growth era. The Mema station is a marvel of scale, housing six massive pumps capable of moving 330 cubic meters of water per second. It is an expression of 20th-century confidence in the face of nature.

Yet, this steel defense has an emotional core. On the left bank of the Shirinashi River water gate stands a Cenotaph/Memorial Monument. It is a necessary stop for any visitor, honoring those lost to past storm surges. It elevates these engineering marvels from mere infrastructure to sites of remembrance. The water gates are not just gates; they are a vow that the tragedies of the past will not be repeated.

The Poetry of Resilience

Osaka’s Minato Ward is a living historical document written in soil, brick, and steel. It is a place that has transformed waste into a mountain, war-torn ruins into a new foundation, and the threat of flooding into a technological shield. This is the "Poetry of Resilience"—a story of sacrifice and remembrance where the community has repeatedly chosen to stay, to build, and to rise.

When we engage in "layered observation" of a city, we find that the most beautiful landmarks aren't always the tallest or the brightest. Often, they are the ones partially buried beneath our feet, or the ones standing guard against the tide.

For more explorations into the hidden layers of the world’s global cities, subscribe to the Lawrence Travel Stories newsletter.

Planning Your Historical Walk

How to Get There The ward is easily accessible via the Osaka Metro Chuo Line to Osakako Station.

Recommended Walking Route

- Tenpozan Park: Begin at the "lowest mountain," locating the kōtōrō site and the Ukiyo-e pottery tablets on the seawall.

- Sumitomo Red Brick Warehouses: Walk south to experience the heavy industrial aesthetic of the Taisho era.

- Chikko and Yunagi Neighborhoods: Venture into the residential blocks to find "sunken" first floors and manhole covers that reveal the 2-meter land raising of 1946.

- Shirinashi River Water Gate: Conclude at the left bank to view the massive water gate and pay respects at the memorial cenotaph.

Nearby Accommodation The Chikko area features several boutique stays housed in older structures, offering a chance to experience the port's atmospheric "frozen time" after the crowds have departed.

Nearby Tours Look for specialized "Osaka Harbor Heritage" walking tours, which provide expert commentary on the Meiji-era engineering of Johannes de Rijke and the 20th-century flood control systems.

References

- 先人に学ぶ ~大阪港150年史から~, accessed October 12, 2025

- 1897(明治30)年 元大阪府知事西村捨三の指揮の下、築港工事に着手, accessed October 12, 2025

- 港区(大阪市)の古い町並み, accessed October 12, 2025

- 本当に? 港 区 を 2 m持 ち上げる! - 大阪市, accessed October 12, 2025

- 大阪市内の高潮対策について, accessed October 12, 2025

- 海洋辞典Ocean Dictionary, 一枚の特選フォト「海 & 船」Ocean and ..., accessed October 12, 2025

- 大阪市港区の観光施設・名所巡りランキングTOP4 - じゃらんnet, accessed October 12, 2025

- 天寶山 - 大阪市, accessed October 12, 2025