(ENG) 5 Hidden Stories That Will Change How You See Hong Kong's Wan Chai

Wan Chai’s vibrant modern identity is built upon forgotten coastlines, sealed over wartime scars, sustained by communities, and captured in art.

I often go to Wan Chai, mainly to see the book fair and other exhibitions at the Wan Chai Convention and Exhibition Centre, and to enjoy food in the old district of Wan Chai Market. As for the history of Wan Chai, I actually know nothing about it.

灣仔洪聖古廟 Hung Shing Temple > 修頓遊樂場 Southorn Playground > 藍屋建築群 The Blue House Cluster

Listen attentively to the historical stories told in detail

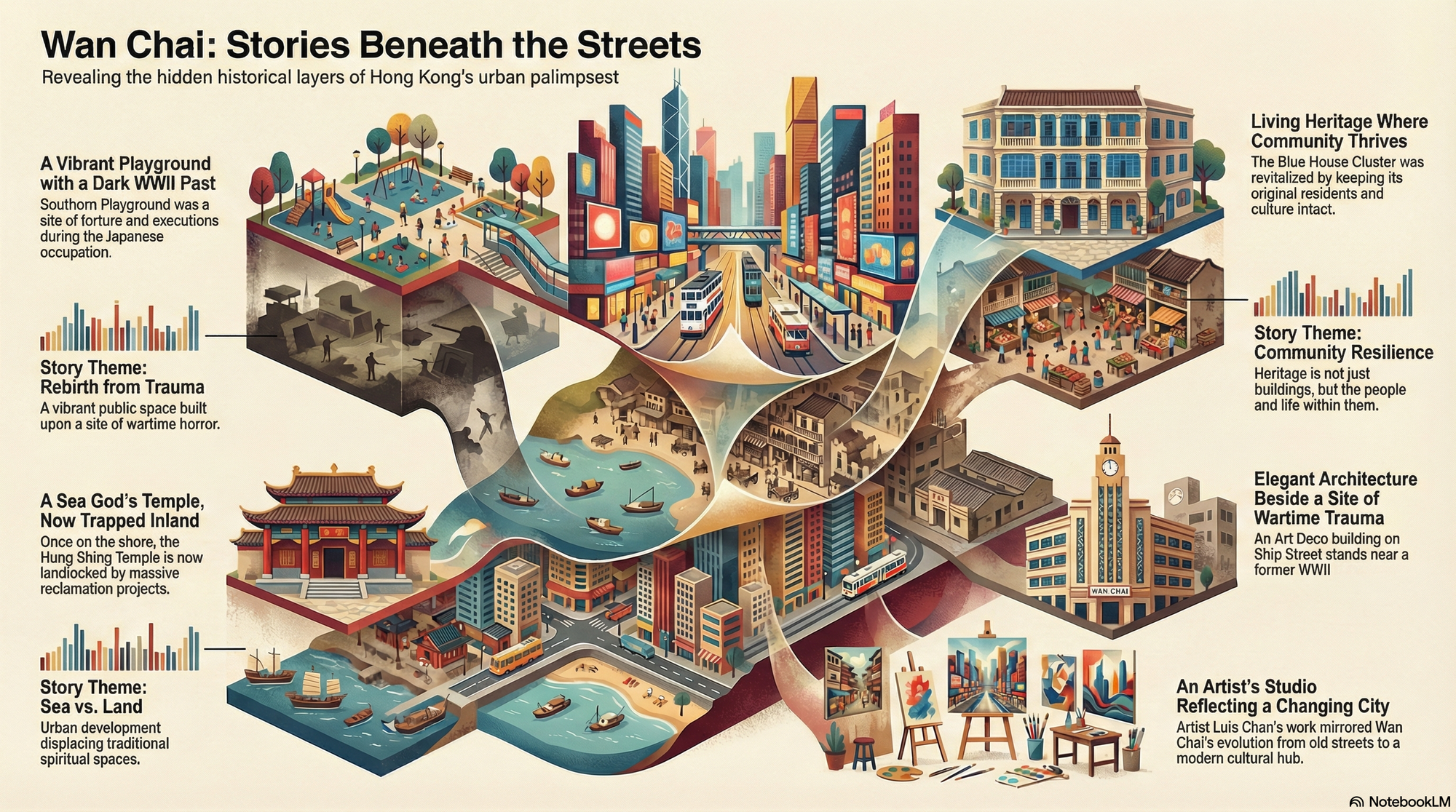

To the casual observer, Hong Kong Island's Wan Chai is a dazzling spectacle of modernity. It’s a district of gleaming skyscrapers, a world-class convention center jutting into Victoria Harbour, and streets that thrum with an electric, neon-lit energy well after midnight. This is the Wan Chai of postcards and business trips—a vertical city defined by its relentless forward momentum. But beneath this polished surface lies a palimpsest, a scroll of history that has been written, erased, and written over for more than a century. This ground holds the ghost of a forgotten coastline, the deep scars of wartime trauma, and the defiant spirit of communities that refused to be swept away by the tides of development.

What if the ground beneath your feet holds stories of forgotten coastlines, buried secrets, and artistic revolutions? To truly understand this district is to learn to read its hidden layers. We will now unveil five of these stories—of a sea god exiled from his ocean, a playground built upon a site of tragedy, a tenement that breathes with living history, a street of jarring contrasts, and an artist who captured the district’s chaotic soul. These are the keys to unlocking the true, multi-layered identity of Wan Chai.

The Sea God's Exile: A Temple That Lost Its Ocean

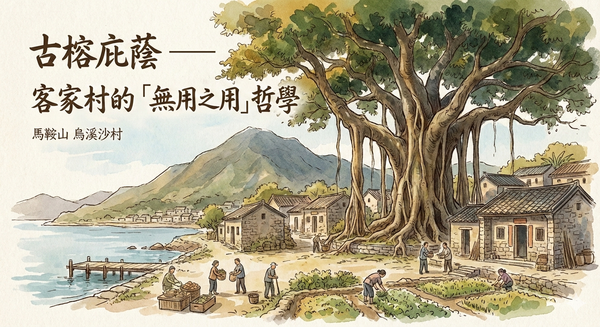

To comprehend Hong Kong is to first understand its foundational act of creation: the conquest of the sea. Nowhere is this story more poignant than in Wan Chai, where massive land reclamation projects didn't just physically reshape the map; they spiritually rewired the district's very soul. The tale of the Hung Shing Temple is the most dramatic illustration of this profound transformation.

The temple is a shrine dedicated to Hung Shing, a powerful god of the southern seas and a guardian of the fishermen who once made their living along Wan Chai's original shoreline. When it was established before 1847, the temple stood exactly where it should: overlooking a shallow bay, its doors open to the scent of salt and the sound of lapping waves. Today, in a deep and profound irony, it is marooned, landlocked amidst the roaring traffic of Queen's Road East. The area’s early identity, however, was never one of simple faith alone; it was a complex mix of grassroots belief and the morally ambiguous wealth of the colonial opium trade that flourished nearby on streets like Spring Garden Lane.

In the 1920s, a monumental reclamation project began. The nearby Morrison Hill was leveled, its earth used to fill in the bay, pushing the coastline hundreds of meters north. This engineering feat effectively exiled the sea god from his domain. The act serves as a powerful metaphor for Hong Kong's larger journey: a shoreline of faith and dubious commerce, both buried under the concrete of modern ambition. As the city pivoted from a maritime society to one dominated by real estate, the deities who once commanded the waves found themselves trapped in a concrete jungle.

When a city's economy shifts from the sea to the land, the gods who once guarded the waves become prisoners of concrete, symbols of a spiritual world displaced by urban ambition.

To find this hidden gem, visit the Hung Shing Temple and the tiny, adjacent Wang Hoi Kwun Yam Temple. The latter’s name literally translates to "Sea-viewing Guanyin Temple"—a silent, stone testament to its lost geography. Stand before them and perform an act of historical imagination: close your eyes, block out the traffic, and try to hear the waves that once broke at your feet. It is an experience that reveals how some buried histories are not just of land, but of human trauma.

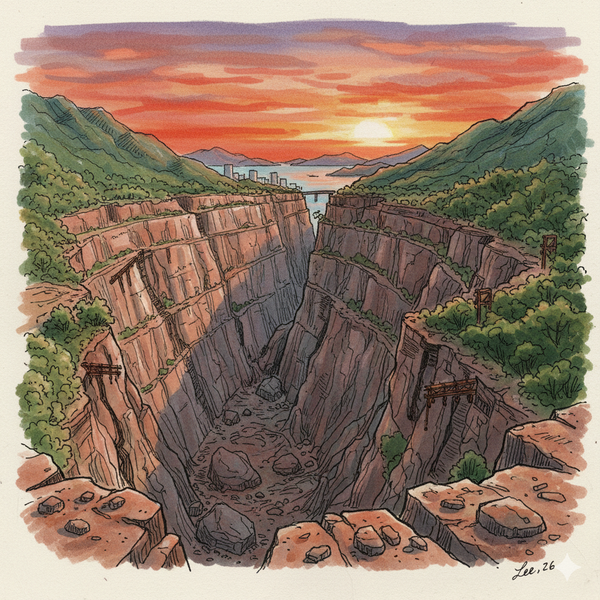

The Playground's Shadow: Trauma and Resilience at Southorn Playground

Walk through Wan Chai today and you will inevitably be drawn to the vibrant energy of Southorn Playground. Often called the most popular patch of reclaimed land on Hong Kong Island, it is a constant hive of activity—basketball games under the floodlights, community gatherings, and fervent political rallies. It is a space of life, sweat, and laughter. Yet, this place of extreme vitality is built directly upon one of the district’s deepest and darkest wounds.

During the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong in World War II, this very site was commandeered by the Japanese military and used as a "district administration office." This innocuous name masks a horrific reality: it was a place where countless innocent civilians were interrogated, tortured, and executed. The bodies of the victims were unceremoniously buried right where they fell, under the earth of what would later become a playground. The tragedy is sharpened by a heartbreaking irony: the playground was originally named to commemorate Mrs. Southorn with the hopeful intention of "leaving the children a piece of sky forever." Instead, this space dedicated to innocence became a theater of brutality.

This makes Southorn Playground a "traumatic palimpsest." The modern joy and kinetic energy of the community are layered directly over a site of immense suffering. This history has not been entirely erased; it lingers in local ghost stories, which serve as a form of cultural resistance—a low whisper of memory against the loud noise of modern life. The city, perhaps unconsciously, made a choice.

The city chose to build a place of extreme vitality upon its deepest wound, as if hoping the daily clamor of life could drown out the silent screams from the earth below.

The hidden gem here is Southorn Playground itself. A visit is not simply an opportunity for people-watching; it is a moment to reflect on how our public spaces can both conceal and embody our collective memories. The laughter you hear today is a testament to resilience, but it echoes across a landscape of profound historical sacrifice. This story of suppressed history gives way to another, where history is not buried but actively and vibrantly kept alive.

The Blue House's Living Soul: Where Heritage Breathes

When a city confronts its past, it faces a critical question: should historic buildings be preserved as static, lifeless museums, or can they continue to function as living, breathing parts of the community? The Blue House Cluster in Wan Chai offers a powerful and inspiring answer.

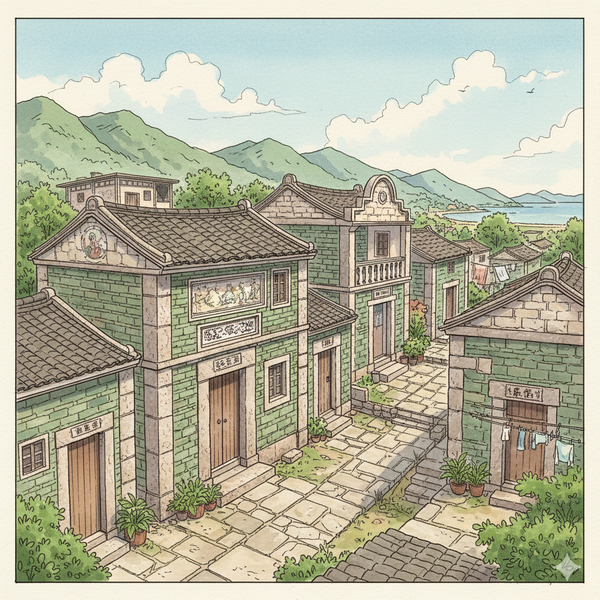

Tucked away on Stone Nullah Lane, this striking collection of blue, yellow, and orange pre-war tong lau (tenement buildings) is more than just beautiful architecture. Its history is woven into the very fabric of the community it served. For decades, it was a complete ecosystem of grassroots support: it housed a free school for local children, a fishmongers' association for economic cooperation, the renowned martial arts school of Lam Cho, and a traditional Chinese medicine clinic. Together, these institutions represented the community’s power of self-protection, self-healing, and self-sufficiency.

What makes the cluster exceptional is its revitalization philosophy. The "Viva Blue House" project was founded on the radical principle of "leaving residents and houses." Unlike so many heritage projects that gentrify neighborhoods and displace their original inhabitants, this initiative fought to keep the local community intact. Today, the Blue House is a model of "living heritage," where the neighborhood's soul—its stories, relationships, and daily rhythms—is preserved right alongside its colourful walls.

The true value of a heritage building is not in its silent walls, but in the dynamic community spirit it continues to shelter. It proves that history can have a heartbeat.

Your destination is The Blue House Cluster on Stone Nullah Lane and the Hong Kong House of Stories housed within it. This is not a traditional museum. It is a place to witness the continuity of grassroots life and celebrate a community's successful struggle to save its home. But while the Blue House showcases a story of harmony, other streets in Wan Chai reveal a much sharper contrast between beauty and brutality.

The Art Deco Secret on a Street of Warped Memories

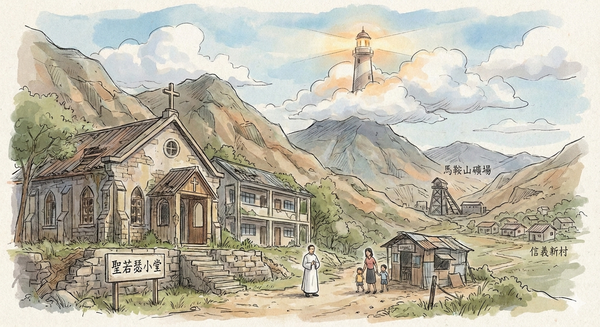

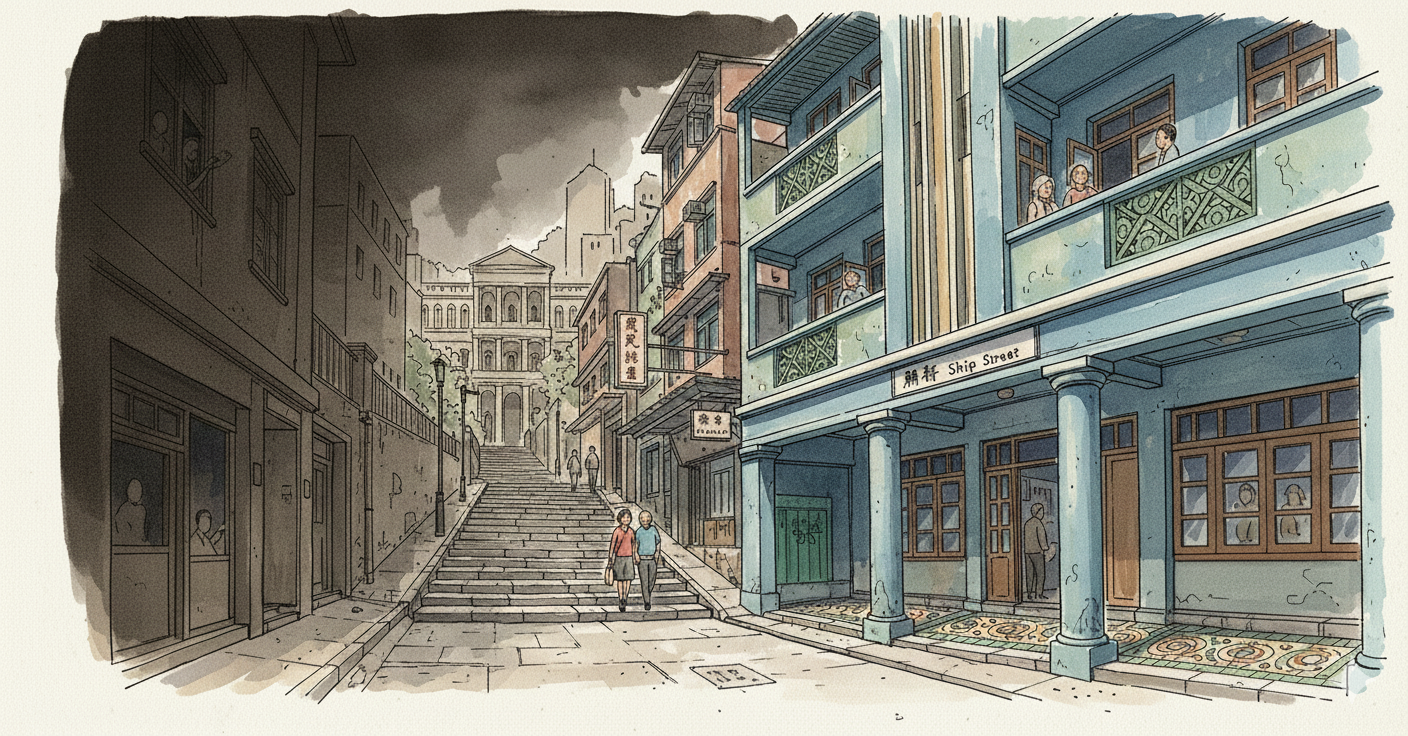

Ship Street is one of Wan Chai's most atmospheric hidden lanes—a tiered stone staircase that climbs away from the district's main thoroughfares. Its very name is a ghost of a forgotten geography, a clue to its past proximity to the old Johnston Road pier. Like the exiled Hung Shing Temple, it is haunted by a lost coastline, reminding us that much of Wan Chai is built on erased maritime memories. This short street encapsulates the district’s contradictory identity, holding both exquisite beauty and the shadows of profound cruelty in startling proximity.

Halfway up the steps stands No. 18 Ship Street, a Grade II historic building completed in 1937. It is a masterpiece of pre-war architectural elegance, blending Western and Chinese features. Look closely at its facade and you will see the beautiful, geometric balcony railings in the Art Deco style popular in the 1930s, and inside, patterned tile floors that speak to the sophisticated aesthetic of the era's middle class.

But this elegance exists in a deeply warped context. Just a stone's throw away, at the top of the street, lie buildings like the infamous Nam Koo Terrace, which during the Japanese occupation was used as a military "comfort station"—a brothel where women were systematically brutalized. The presence of such profound human suffering so close to a site of refined architectural grace creates an intense and unsettling historical dissonance.

This street forces us to confront a difficult truth: that aesthetic grace and profound human cruelty can occupy the very same space, separated by nothing more than a few stone steps.

The hidden gems here are twofold. First, the exquisite facade of No. 18 Ship Street, where you should pause to appreciate the delicate Art Deco details. Second, the atmospheric stone slab steps of Ship Street itself. As you walk them, feel the layers of history under your feet—the hopeful ambitions of a pre-war family and the dark wartime memories that haunt the lane's upper reaches. It is this chaotic, multi-layered energy that one local artist managed to capture perfectly in his work.

The Kaleidoscopic Eye: Seeing Wan Chai Through an Artist's Gaze

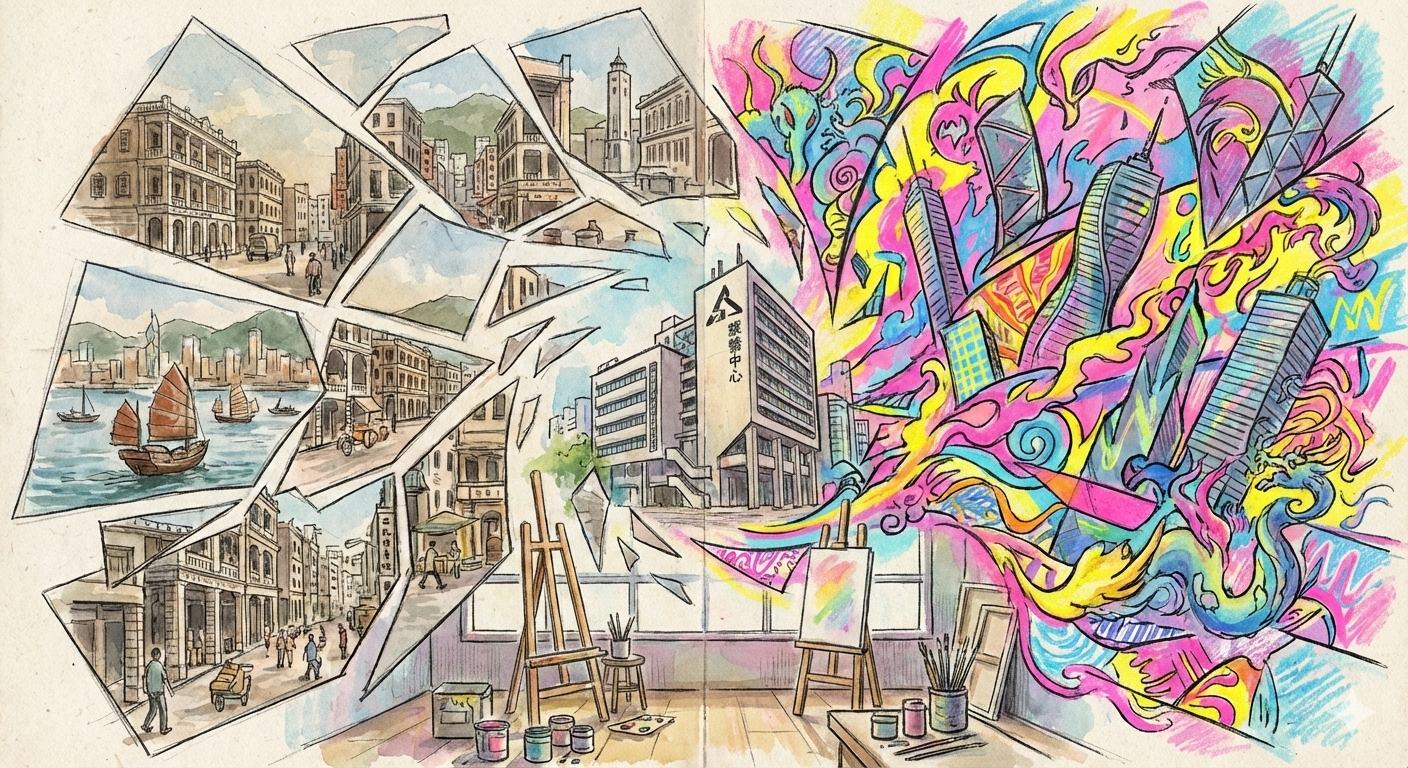

Sometimes, to truly understand a city's soul, you must see it through the eyes of its artists. Luis Chan (1905-1995), a pivotal figure in Hong Kong's modern art movement, provides a remarkable lens through which to view Wan Chai’s own dramatic evolution from a colonial-era district to a sprawling metropolis.

Known in his early career as the "King of Watercolour," Chan began by painting detailed, realistic landscapes of Hong Kong. However, as the city around him transformed after the war, so did his art. His style evolved into a vibrant, fantastical, and almost chaotic explosion of abstract colour and dreamlike figures. This artistic journey perfectly mirrors Wan Chai's own development. His early realism captured the district as a tangible, colonial place, while his later "kaleidoscopic" works reflect the disorienting, energetic, and explosive transformation of Hong Kong into a complex modern city.

In the 1970s, a new phase of land reclamation created the northern edge of Wan Chai, and on this new ground, a new cultural landmark was built: the Hong Kong Arts Centre. In a moment of beautiful historical symmetry, this institution of the "new Wan Chai" now pays homage to the old master by recreating his original Wan Chai studio within its modern walls.

An artist's style is a seismograph of his time. Chan's paintings did not just depict Wan Chai; they absorbed its frenetic energy and translated its chaotic transformation into a new visual language.

For your final destination, head to the permanent exhibition "Luis Chan's Studio" at the Hong Kong Arts Centre. Stepping inside is like entering a portal into the creative heart of an artist who not only lived in Wan Chai but chronicled its very soul. This artistic perspective provides the perfect way to conclude our journey through the district’s hidden layers, seeing them fused together in a vision of colour and motion.

Your Invitation to Look Deeper

Tying these five stories together reveals Wan Chai as an "Eternal Palimpsest." The city’s vibrant modern identity is built quite literally upon forgotten coastlines, sealed over wartime scars, sustained by living communities, and captured in visionary works of art. Each layer adds depth and texture to the whole, reminding us that no city is ever just one thing.

The ultimate takeaway is this: the real "hidden gems" of any city are not just the places themselves, but the stories they hold and the conscious act of uncovering them. It is in looking past the neon glare to find the faint outlines of the past that we connect with a place's true character.

The next time you walk through a familiar city, what forgotten histories might be stirring just beneath your feet?