(ENG) A Walker's Guide to 4,000 Years of Ma Wan's Hidden History

Ma Wan is a place to stand still and recognize the tension between a Neolithic burial ritual and an Instagram-ready mural.

舊九龍關石碑 the Old Kowloon Customs Stone Tablet > 馬灣新舊村 Ma Wan (New & Old)

Because I owned three dogs, I lived in Ma Wan for three years, two years in Park Island, and one year in a village house. Ma Wan is known as Hong Kong's eco-island, where residents are not allowed to drive private cars. During those three years, I left quite a bit of foot hair on the entire island.

Listen to the historical stories told in detail (For subscribers only)

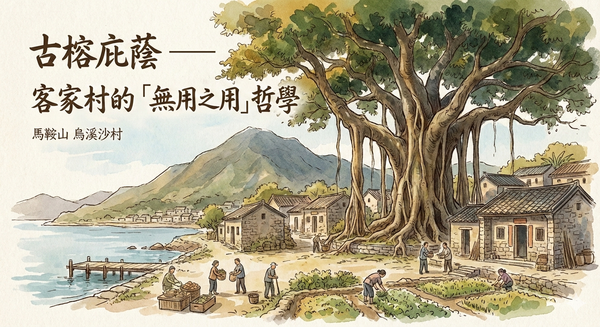

Wedged between the islands of Tsing Yi and Lantau, Ma Wan is known to most as a landmark defined by the colossal Tsing Ma Bridge that soars above it, a critical artery of modern Hong Kong. But beneath the shadow of this engineering marvel lies a history far deeper and more complex than steel and concrete. This small island is a historical prism, refracting stories that stretch back an astonishing 4,000 years, from a Neolithic settlement that rewrote Hong Kong’s prehistory to the final, fading grasp of an imperial Chinese dynasty. This profound past isn't confined to museums; it’s etched into the landscape, waiting to be discovered on foot. This guide will walk you through Ma Wan’s layered past by uncovering five profound stories hidden in plain sight, transforming a simple island visit into a journey through time.

Hong Kong's Oldest Secret: A Neolithic Woman and Her Ritual Smile

Ma Wan’s story begins not with skyscrapers or colonial trade, but thousands of years before, in a time of ritual and mystery. The island was thrust onto southern China's prehistoric map in 1997, when a rescue excavation at a site named Dong Wan Tsai North unearthed finds so significant they were named one of China's top ten archaeological discoveries of the year. In 2001, this achievement was compounded when the site was also named one of the "100 great archaeological discoveries in China in the 21st century," reinforcing Ma Wan’s unique importance in understanding the deep past.

The "Ma Wan Woman" Discovery

At the heart of the discovery was the skeleton of a woman from 4,000 years ago, approximately 40 years old at her death. In Hong Kong’s humid, acidic soil, finding such remains is rare; finding a perfectly preserved skull is nothing short of an archaeological miracle. Researchers believe the "Ma Wan Woman" was preserved by a unique, naturally occurring layer of alkaline substances that protected her from the elements. This fluke of geochemistry provided a direct link to the island's earliest inhabitants.

The most fascinating detail, however, was what was missing. Her two front teeth had not fallen out but were deliberately removed, likely as part of a coming-of-age ceremony around the age of 16 or 17. This practice of ritual tooth avulsion connects the people of Ma Wan to a broader cultural identity shared across the Pearl River Delta, suggesting a society with complex social norms and rites of passage that went far beyond simple survival. Found with her were other clues to their spiritual life: a stone jue (a ring-shaped ear ornament) was still in her left ear, and a smaller one had been placed in her mouth, providing direct evidence of their burial customs.

Where to Find This Story Today

This ancient world can be encountered at the Ma Wan Park Heritage Centre. Housed in a beautifully preserved former village school, the Fong Yuen Study Hall, the centre features a recreated model of the "Ma Wan Woman." Here, you can come face-to-face with this ancestor, seeing a forensic reconstruction based on her skull and allowing a 4,000-year-old story to feel strikingly present.

While Ma Wan's story begins in the quiet rituals of prehistory, its more recent past is defined by the dramatic clashes between empires.

The Seven-Foot Border: Where a Chinese Dynasty's Power Ran Out

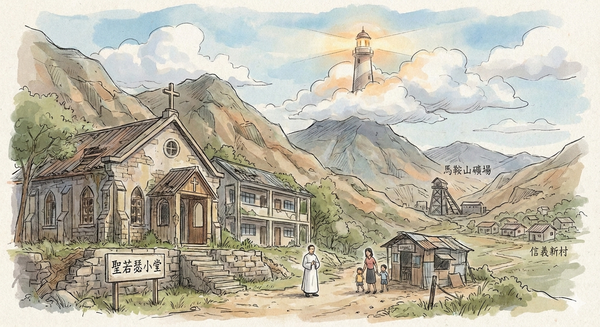

In the late 19th century, Ma Wan found itself on the front line of a geopolitical struggle. The Qing Dynasty, weakened but determined, was fighting to control trade and curb the rampant opium smuggling fueled by encroaching Western powers. Due to its strategic position guarding the channel, Ma Wan became a critical outpost in this desperate attempt to assert sovereignty at the very edge of British influence.

The Story of the Kowloon Customs Post

The Qing government established a customs post on Ma Wan to monitor trade and collect taxes, a crucial effort to maintain economic and administrative control on the border of British-held territory. In 1897, when officials planned to build a new facility, they clashed with local villagers who refused to give up their land. The conflict resulted in an unusual and telling compromise. The government agreed to limit the width of its access road to just "seven feet," a promise they immortalized on a stone tablet to appease the village. This small victory for the locals, however, would soon be overshadowed by a much larger geopolitical shift.

A Monument to Faded Power

The profound irony is that this stone tablet, intended to mark an assertion of Qing authority, instead became a monument to its final moments. Just one year later, in 1898, Britain leased the New Territories for 99 years. The border instantly shifted, rendering the entire customs post and its seven-foot road completely obsolete. The Qing Dynasty's last administrative expansion in the region was erased almost as soon as it was carved in stone.

Where to Find This Story Today

Travelers can still find the Old Kowloon Customs Stone Tablet on the island. It stands today as a quiet, powerful artifact. More than just an old rock, it is a physical marker of a vast empire’s final boundary line—a tangible piece of history that tells a sweeping story of sovereignty won and, almost immediately, lost.

From the macro-politics of empires, our journey now shifts to the micro-culture of the island's longest-standing community: the Tanka fishermen.

The Sacred Ground That Smelled of Shrimp Paste

For centuries, Ma Wan’s identity was shaped by the sea and the Tanka fishing community who made their lives on its waters. At the heart of this maritime society was not a government building or a market, but the Tin Hau Temple—a spiritual and communal anchor for a people whose survival depended on the whims of the ocean.

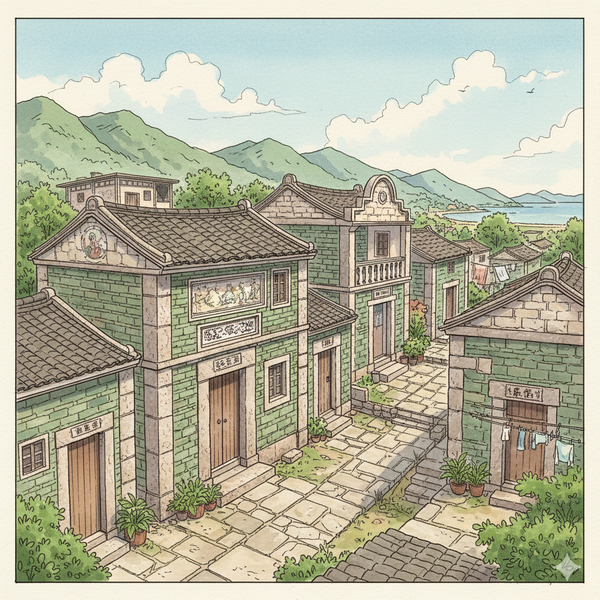

The Temple at the Heart of the Village

Built in 1857 by local fishermen, the temple was dedicated to Tin Hau, the goddess of the sea, who they prayed to for protection and bountiful catches. But this temple was far more than just a place of worship. The large, open ground in front of it served a crucial economic function as the communal space for drying shrimp paste, a staple of the village economy. Imagine a space where the sacred and the secular were inseparable—where the holy scent of sandalwood incense from the temple altar mingled with the sharp, salty aroma of fermenting shrimp paste drying under the sun, the air thick with prayers and the sounds of village commerce.

A Broken Connection

Modern development has dramatically altered this landscape. The traditional stilt houses that once lined the shore are gone. The temple, though preserved and listed as a Grade III historic building in 2010, has been relocated just outside the primary tourist park. Most significantly, the former shrimp paste drying ground—once the vibrant heart of the village economy—is now a scenic rest area for tourists. The organic link between faith, community, and livelihood has been severed.

Where to Find This Story Today

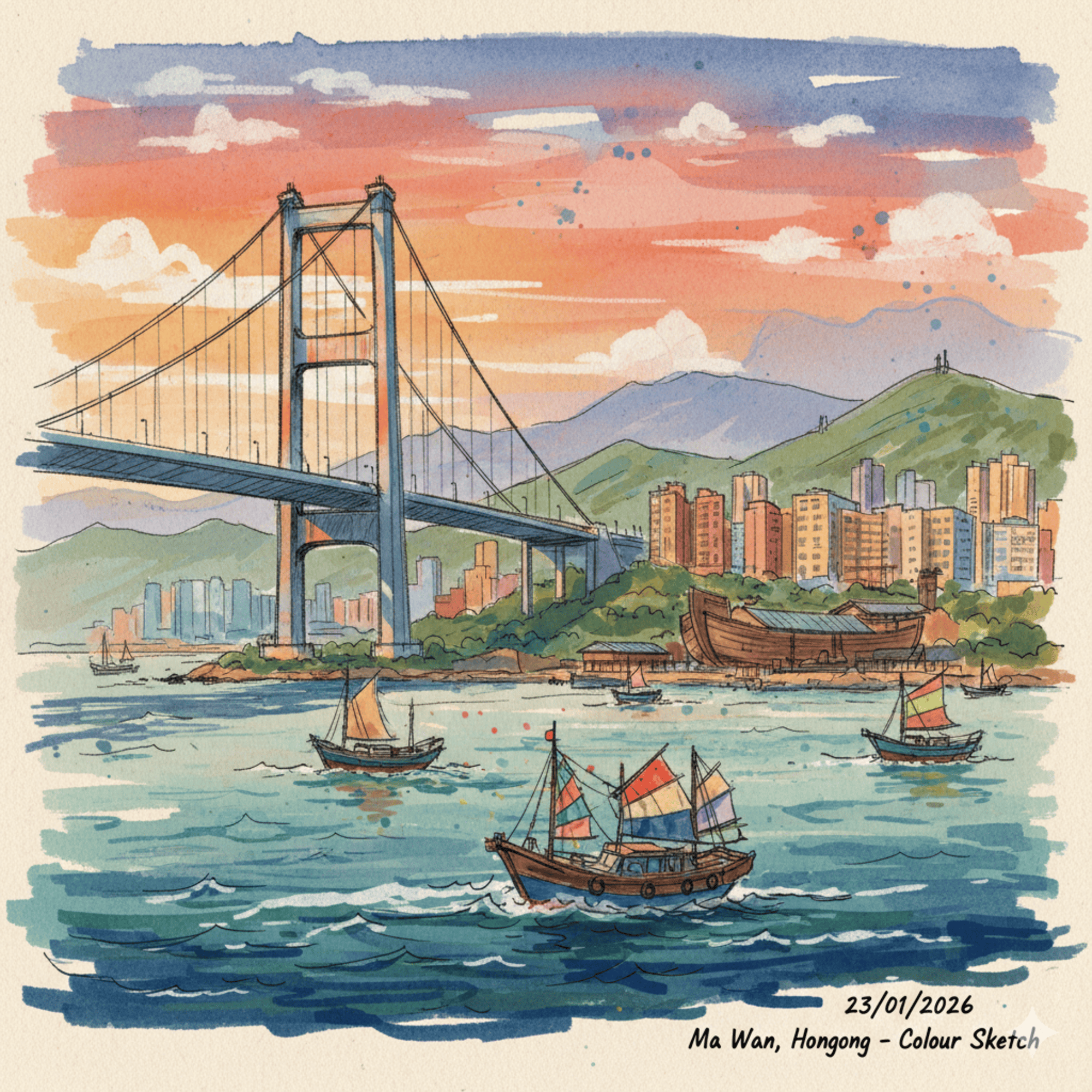

Visit the relocated Ma Wan Tin Hau Temple and then walk to the nearby Old Ma Wan Pier. Here, where a few locals still cast their fishing lines, you can witness a stunning juxtaposition: the historic temple set against the breathtaking backdrop of the modern Tsing Ma Bridge. This single view serves as a powerful visual metaphor for Ma Wan’s entire history, capturing the tension and beauty between the island's past and its present.

Just as faith was central to the community, so too was the pursuit of knowledge, which took place in a small, humble schoolhouse nearby.

The School Where Lessons Came with the "Pok Pok" of a Fan

In the past, before Hong Kong had a universal public education system, learning was a community-driven effort. On Ma Wan, the Fong Yuen Study Hall was not a grand institution but an intimate and essential pillar of village life, embodying the community’s commitment to its children’s future.

The Story of the "Pok Pok Zhai"

Built in the 1920s-30s, the Fong Yuen Study Hall was a typical two-story village school. It earned a charming local nickname: a "pok pok zhai." This name came from the distinct "pok pok" sound made by the teacher's fan as it tapped the hands or heads of students to keep them focused on their lessons. The name perfectly evokes the simple, strict, and dedicated nature of village education, painting a vivid picture of a classroom filled with the hum of recitation and the rhythmic tap of the teacher's fan.

A Cycle of Knowledge and Heritage

This building's story is one of remarkable continuity. After its time as a school, the Fong Yuen Study Hall was carefully restored and converted into the Ma Wan Park Heritage Centre. The very space once dedicated to teaching classic texts to village children now serves a new educational mission: teaching visitors about the island’s long and layered history. It houses not only the reconstruction of the "Ma Wan Woman," but also artifacts from Tang and Qing dynasty kilns discovered on the island. The building's mission evolved from transmitting a community's living culture to its children, to preserving the island's deepest ancestral memories for the world. It represents a poignant shift from teaching the present to curating the deep past.

Where to Find This Story Today

When you visit the Fong Yuen Study Hall, take a moment to appreciate the building itself. It tells two stories at once: the 20th-century tale of a village school filled with young students, and the 21st-century story of a museum preserving 4,000 years of human history for all to see.

While this building represents a successful act of preservation, the fate of the island's main village tells a much more complex and controversial modern story.

When a Rainbow Village Hides a Ghost Story

Ma Wan's most dramatic transformation was triggered by the construction of the Tsing Ma Bridge. While the bridge connected the island to the world in a new way, it led to the profound disconnection—and eventual abandonment—of its historic fishing village.

From Abandonment to "Rebirth"

Between 2003 and 2005, the residents of the old village were relocated to modern high-rises. Their former homes were fenced off and left to decay, creating a ghost town in the heart of the island. Years later, a developer launched the "Ma Wan 1868" project to revitalize the area. Its most prominent feature is the "Rainbow Village," where the old houses were painted in vibrant, cheerful colors to create a picturesque attraction reminiscent of Italy’s Cinque Terre, complete with artistic murals, urban farms, and planned restaurants. It was designed to be beautiful, modern, and perfectly Instagrammable.

The Controversy of "Aesthetic Replacement"

This colorful rebirth has led to sharp criticism from conservation advocates. This transformation is a textbook example of what critics call "aesthetic replacement," where the authentic, complex history of a place is papered over with a bright, simplified, and internationally generic look. As one critique noted:

The real loss was not the individual houses, which may have had low conservation value, but "the entire village atmosphere."

While beautiful, the vibrant colors risk obscuring the difficult story of community displacement that lies beneath. The transformation turns a site of memory and loss into a cheerful theme park, prioritizing aesthetics over authentic history.

Where to Find This Story Today

The Ma Wan 1868 Rainbow Houses should be the final stop on your historical walk. Enjoy the artistry and the beautiful scenery, but do so with awareness. Look past the colorful facades and consider the silenced history of the community that once lived and worked here. It is a place that invites both visual delight and thoughtful reflection on what is gained, and what is lost, in the name of progress. This final stop forces us to confront the central question of modern heritage: what is the line between revitalization and the erasure of memory?

The Island of Bridges and Memories

A walk through Ma Wan is a journey through five distinct layers of Hong Kong's identity: from its deep Neolithic roots and the fading authority of Imperial China to the vibrant life of its fishing communities, the quiet dedication of its village educators, and the complex realities of modern development. This island proves that it is far more than just a place to see a bridge; it is a place to stand still and recognize the tension between a Qing dynasty boundary stone and a global shipping lane, between a Neolithic burial ritual and an Instagram-ready mural.

As we walk through places like Ma Wan, how do we learn to see both the beauty of what's been created and the memory of what's been lost?

To explore more hidden histories, consider subscribing to our newsletter for stories that go beyond the guidebook.

Keep Reading

Explore Our Complete Guide to Historical Travel in Hong Kong

A Walking Tour of '5 Hidden Stories That Redefine Hong Kong's Kowloon City'