(ENG) Beyond the High-Rises: Walking Through the 5 Hidden Histories of Hong Kong's Tseung Kwan O

Tseung Kwan O and Hang Hau weave together to tell a single, powerful story of resilience, a place has constantly adapted without being erased.

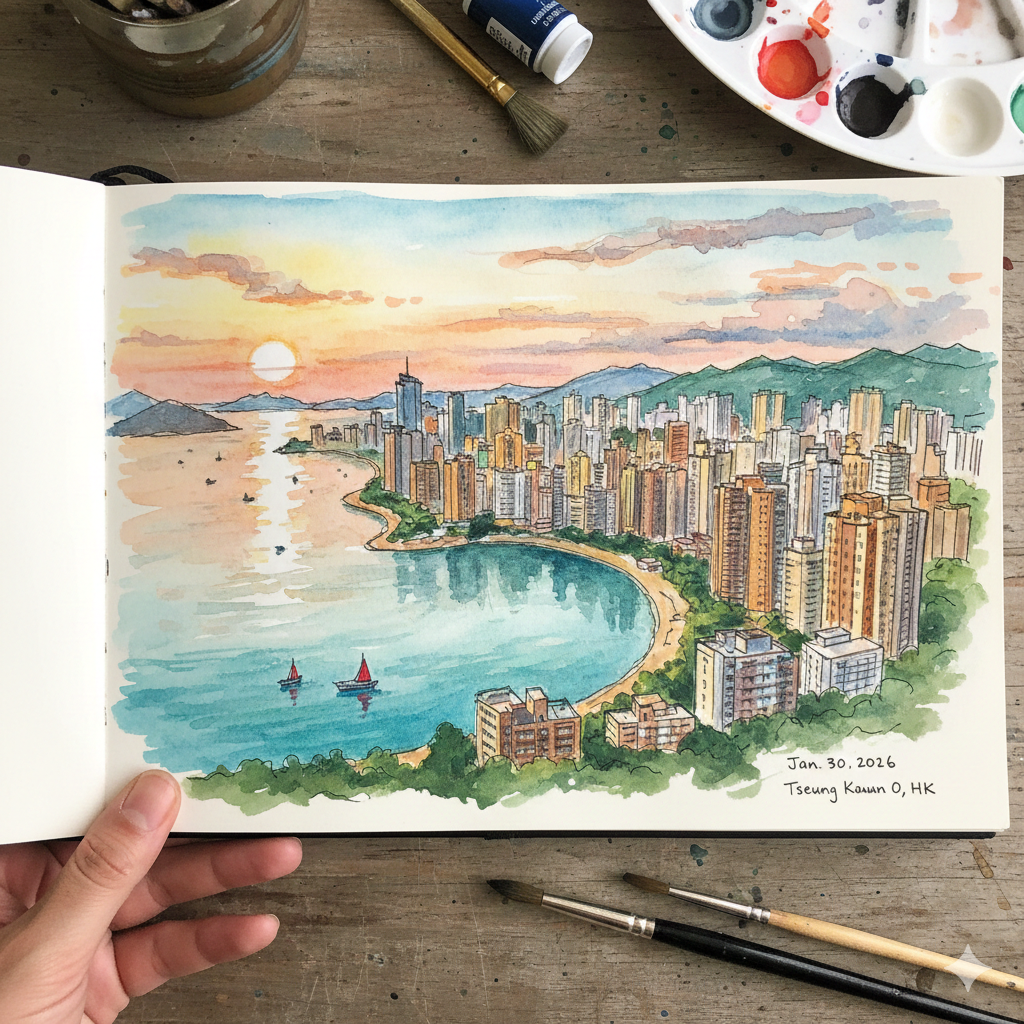

將軍澳風物汛 與 香港單車館公園 the TKO Folk Museum and the Hong Kong Velodrome Park

Listen to the historical stories told in detail (For subscribers only)

To the modern observer, Tseung Kwan O is a landscape of gleaming efficiency—a new town defined by soaring residential towers, seamless public transport, and manicured waterfront parks. It represents Hong Kong’s forward-looking energy, a testament to ambitious urban planning. Yet beneath this polished veneer lies a far older story, a history stretching back centuries, rich with the legends of fallen generals, the faith of seafaring communities, and the fierce spirit of local autonomy. Here, the grounded history of the inland community of Hang Hau weaves together with the grand maritime legends of the bay, creating a story richer than either could tell alone. This guide is an invitation to look past the contemporary cityscape and walk through five surprising historical narratives that still echo here. It is a journey that transforms a simple stroll into an exploration of time, revealing the deep, resilient soul of a place hiding in plain sight.

The Mystery of the General: A Tale of Two Names

A place’s name is rarely a simple label; it is a cultural artifact, a story chosen and told across generations. The name "Tseung Kwan O" (將軍澳), meaning "General's Bay," is a perfect example—a name that reveals a fascinating tension at the heart of Hong Kong’s identity, caught between heroic legend and colonial pragmatism.

The Competing Legends

The most compelling local narratives are rooted in military glory. One legend, set in the Ming Dynasty, tells of a defeated general who retreated to this bay, where he ultimately died from his wounds. In his honor, his followers buried him here, and the cove was forever named after him—a tale of tragic heroism that imbues the landscape with a sense of solemn remembrance.

Another story reaches further back, to the final years of the Southern Song Dynasty. As the imperial court fled the advancing Mongol armies, a loyal general was dispatched to guard the strategic waters off Lei Yue Mun channel, protecting the royal family from a surprise attack. In this version, the bay is named for this dutiful protector, casting it as a vital military outpost in a grand, dynastic struggle. That the community chose to preserve these tales of martial honor speaks volumes about its desire to anchor its identity in a deep and venerable past.

The Colonial Perspective

Juxtaposed with these heroic tales is the area’s more practical English name: "Junk Bay." Its origins are decidedly less romantic. One theory suggests "Junk" was simply a phonetic approximation of the Cantonese "Tseung Kwan." A more widely accepted explanation is literal: the bay was a natural, sheltered anchorage frequently filled with Chinese sailing vessels, or junk boats. To the British colonists and other outsiders, the bay was defined not by ancient generals but by its immediate, practical function as a hub for maritime trade.

A Duality of Identity

This duality is what makes the story of the name so significant. The local preference for the "General" narrative reveals a desire for a romantic, heroic self-image, while the colonial "Junk Bay" name reflects a pragmatic, trade-focused identity. This tension between myth and utility, between war and commerce, is the very essence of Hong Kong's character.

Hidden Gem: The Virtual Monument

To contemplate this history, there is no better place than the Tseung Kwan O Promenade. While no physical statue of a general stands here, the waterfront itself acts as a virtual monument. Walk towards the mouth of the Lei Yue Mun channel, the strategic point the Song Dynasty general would have defended, and gaze out at the water.

The modern promenade offers a space to ask a fundamental question: Is this land defined by war or by trade? This conflict of ideas provides a travel experience far deeper than mere sightseeing.

While the legends of the bay exist in story and memory, our next stop takes us inland to Hang Hau, where history is not just told, but can be touched—cast in iron and carved in stone.

The Daoguang Bell: A Temple's Declaration of Power

While the bay’s history is steeped in legend, the story of the inland community of Hang Hau is anchored by a solid, physical artifact: the Hang Hau Tin Hau Temple. This temple is more than a place of worship; it is the most reliable timekeeper for Old Hang Hau, a testament to a community’s faith, wealth, and enduring independence.

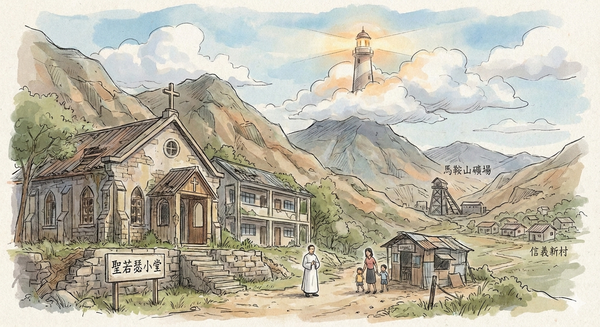

A Foundation of Faith and Fortitude

Founded in the early Qing Dynasty as a humble shrine, the temple underwent its most significant transformation in 1840. In that year, the local community raised the funds to relocate and reconstruct it on a grander scale. The timing is remarkable. In 1840, on the very eve of the First Opium War, the region was entering a period of immense uncertainty. That the Hang Hau community could undertake such an ambitious project at this moment demonstrates considerable pre-colonial economic strength and sophisticated social organization, built on a stable foundation of fishing and farming.

An Irrefutable Artifact

The temple’s most vital piece of evidence is a large cast-iron bell hanging within its halls. Etched clearly onto its surface are the characters for "Daoguang 20th Year"—1840. This bell is not mere decoration; it is an irrefutable time-stamp. It solidifies the temple's history and serves as a powerful testament to the community's devotion to Tin Hau, the Goddess of the Sea and the divine protector of the fishermen from the surrounding Tin Ha Wan and Fat Tau Chau villages. The bell represents an ancient covenant between the people and their deity, a promise of protection in exchange for unwavering faith.

The Subtlety of Self-Rule

Unlike the grand, government-sponsored temples of imperial China, with their elaborate roof sculptures and symbolic grey bricks, Hang Hau's temple speaks a different language. Its unadorned ridge and practical red tiles are not a sign of poverty, but a declaration of a practical, resilient faith—a community that invested in substance over ceremony. These details, combined with its status as a private temple not managed by the government-affiliated Chinese Temples Committee, paint a clear picture: this was an institution built and maintained by the people, for the people.

Hidden Gem: The Temple's Testimony

The Hang Hau Tin Hau Temple is the hidden gem. When you visit, look beyond its role as a religious site. Seek out the 1840 bell to touch a fixed point in history. When I stand before this temple, it's the simple roofline that captures my attention. It tells me that this was a community that poured its resources into its foundations—both literal and spiritual—rather than outward display. This temple was the heart of their world, and its importance extended far beyond matters of the soul.

More Than a Temple: The Lost Political Heart of Old Hang Hau

In traditional societies, sacred spaces often serve crucial secular needs. The most surprising story of the Hang Hau Tin Hau Temple is not its religious significance, but its forgotten past as the region’s de facto political and economic capital. For a time, this temple was the very seat of local power.

An Era of Self-Governance

During the late Qing Dynasty and the early years of the Republic, British colonial administration in the New Territories was still weak and indirect. In this power vacuum, traditional village institutions stepped in to govern. The Tin Hau Temple, as the community's central public space, became the undisputed hub for resolving land disputes, managing scarce water rights, and mediating family conflicts. The area around it was the bustling local market, making the temple the nexus of all commercial and civic life.

A Timeline of Prosperity

The temple's artifacts chart the golden age of this local self-governance. We know of the 1840 bell, which marks the community’s initial investment. But look closely at a couplet on the right side of the temple, and you will find another date: "Guangxu 1st Year," or 1875. The thirty-five years separating these two markers were clearly a period of sustained prosperity. This later addition proves the community was not just surviving but thriving, confident enough to continue investing in its central institution. It was a time when local elders, not distant bureaucrats, held sway.

Hidden Gem: Reimagining the Town Square

Today, the old market square is gone, enveloped by modern housing estates. But adjacent to the temple lies Man Kuk Lane Park, a tranquil Chinese garden that offers a space to reconnect with this lost history. The connection is profound and symbolic. The temple’s side hall is dedicated to Man Cheong, the god of literature and civil order. The park’s name, Man Kuk Lane, translates to "Lane of Literary Melody." This is no coincidence; it is a modern echo of the community’s historical reverence for culture, education, and social harmony.

Use this park not just as a place to rest, but as a stage for your imagination. Picture the bustling market that once stood here, the village elders holding court, and the intricate web of social and economic life that unfolded under the watchful eye of the temple gods.

This era of local autonomy, however, would soon be swept away by one of the most dramatic physical transformations in Hong Kong's history.

From Junk Bay to New Town: A Story of Urban Metamorphosis

The transformation of Tseung Kwan O’s physical landscape is one of Hong Kong's most epic tales of urban development. In the span of just a few decades, this area journeyed from a natural coastline to a functional "backstage" for the city, and finally to the sprawling modern metropolis we see today.

The Stages of Transformation

For centuries, Tseung Kwan O was a natural bay, its sheltered waters providing safe harbor for fishing fleets and trade vessels. As urban Hong Kong grew, however, the bay was assigned a new, less glamorous role. It became, for a time, the site of one of the city's major landfills—a necessary but unseen backyard for a burgeoning population. This period culminated in a massive land reclamation project that completely erased the original coastline, burying the old geography of farms and fishing villages under tons of earth to create the foundation for the new town. The speed of this metamorphosis is difficult to comprehend. The very ground beneath the Velodrome was, within living memory, open water plied by fishing boats. This is not just urban development; it is a geological act of will.

A Curated Memory

Amid this relentless drive forward, a conscious decision was made to preserve the past. The creation of the Tseung Kwan O Folk Museum (將軍澳風物汛) was a deliberate act by the modern city to archive the memory of the landscape it had replaced. The museum functions as a "memory bank," collecting the stories, photographs, and artifacts of the lost bay and its communities. It stands as an official acknowledgment that today's prosperity was built upon the complete transformation of a previous world.

Hidden Gem: A Dialogue Between Memory and Speed

To truly grasp the scale of this change, the most powerful experience is found in the pairing of two adjacent landmarks: the TKO Folk Museum and the Hong Kong Velodrome Park. This walking route creates a profound dialogue between past and present.

First, immerse yourself in the quiet, static history of the museum. Then, step outside and walk to the velodrome, an international-class sporting facility. The contrast is immediate and striking: the silent archives of a forgotten past give way to the dynamic speed and sleek modernity of the cycling track. This journey allows you to physically experience the immense leap in time that defines Tseung Kwan O. This rapid development is a recurring theme in the city's story, which you can explore further in our [[guide to Hong Kong's urban history]].

From the sweeping story of the changing landscape, we now turn to the most intimate layer of history: the people who called this place home.

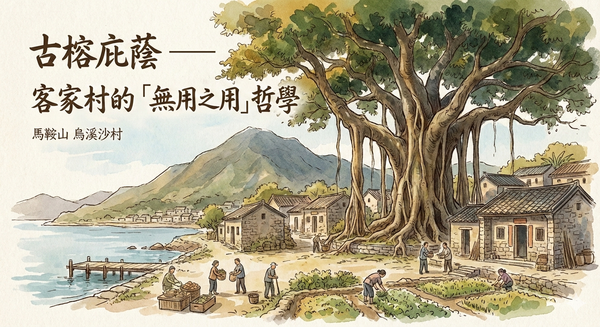

The Cultural Islands: Finding Traces of Village Life Among the Towers

History is not only written by generals and recorded in grand temples; it lives in the quiet, everyday routines of its people. The final and most subtle layer of Tseung Kwan O's past is the faint echo of its original villages, small communities whose lives were intimately tied to the land and the sea.

The Village Economy

Before the new town, the heart of this area was composed of communities like Tin Ha Wan and Fat Tau Chau villages. Theirs was a self-sufficient lifestyle built on a composite economy. They were fishermen, relying on the bounty of the sea and the divine protection of Tin Hau. They were also farmers, cultivating the inland plains to feed their families. This dual reliance on land and sea created a resilient and tightly-knit social fabric, governed by the rhythms of the tides and the seasons.

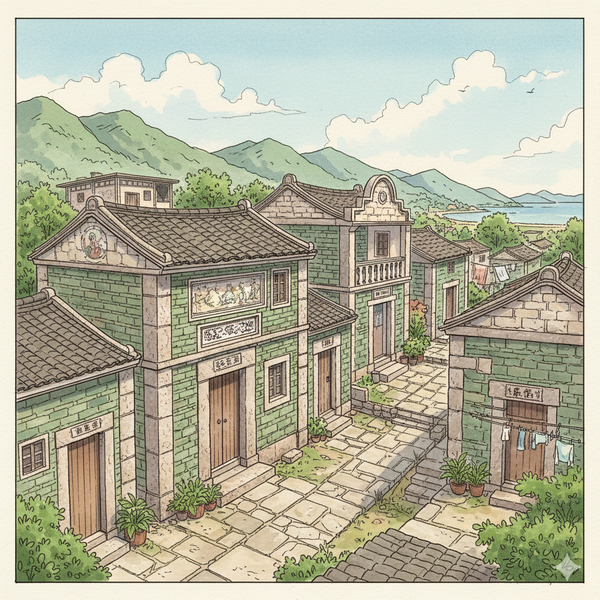

The "Cultural Island" Effect

The sweeping development of the new town was an existential challenge to this way of life. As reclamation advanced and high-rises sprouted, the old villages were surrounded, absorbed, and largely erased. Yet, not everything was lost. In the gaps between the massive residential estates, fragments of the old world survive. An old grey brick wall, a sliver of a traditional roofline, or a lone ancestral hall can still be found. These remnants are what can be called "cultural islands"—physical testaments to a community's resilience in the face of overwhelming modernization.

Hidden Gem: An Act of Urban Archeology

This is the final challenge—an act of urban archeology. Your guide is not a map, but a sense of dissonance. As you walk, ignore the seamless facade of the new town and search for the breaks in the pattern: a patch of weathered grey brick swallowed by concrete, a fragment of a traditional curved roofline peeking out from behind a utility block. These are not ruins; they are testaments. The value of this experience lies not in finding a perfectly preserved building, but in witnessing the stark visual contrast. Seeing a fragment of a humble village home dwarfed by a 40-story apartment block makes the tenacity of the old community palpable in a way no museum exhibit can.

These surviving fragments, like the temple, the legends, and the reclaimed land, all contribute to the rich, layered story of this unique corner of Hong Kong.

Reading the Layers of the City

The five histories of Tseung Kwan O and Hang Hau weave together to tell a single, powerful story of resilience. From the defiant legends of ancient generals and the steadfast faith of a fishing community, to the proud autonomy of the temple-state and the stubborn persistence of village memory in the shadow of skyscrapers, this is a place that has constantly adapted without being erased.

Tseung Kwan O is a palimpsest: a modern landscape written over older, fainter texts. These earlier stories are still visible, but only if you know how and where to look. They remind us that no city is built on a blank slate; it is always a transformation of what came before. True understanding of a place comes from this kind of layered, on-the-ground observation, where a simple walk can become a profound dialogue with the past.

This layered way of seeing a city is at the heart of what we do. It leaves me with a question I carry on every journey, and one I now leave with you: In your own rapidly changing city, what hidden histories lie just beneath the surface, waiting to be rediscovered?

For more stories that uncover the soul of a city, consider subscribing to our newsletter.