(ENG) Five Surprising Histories Hidden in Old Taipei: A Walker’s Guide to Datong District

We see a powerful philosophy of resilience: the tea trade faded, the district did not crumble;, becoming a new kind of cultural currency.

迪化街 Dihua Street > 新芳春茶行 Xinfangchun Tea House

Listen to the historical stories told in detail (For subscribers only)

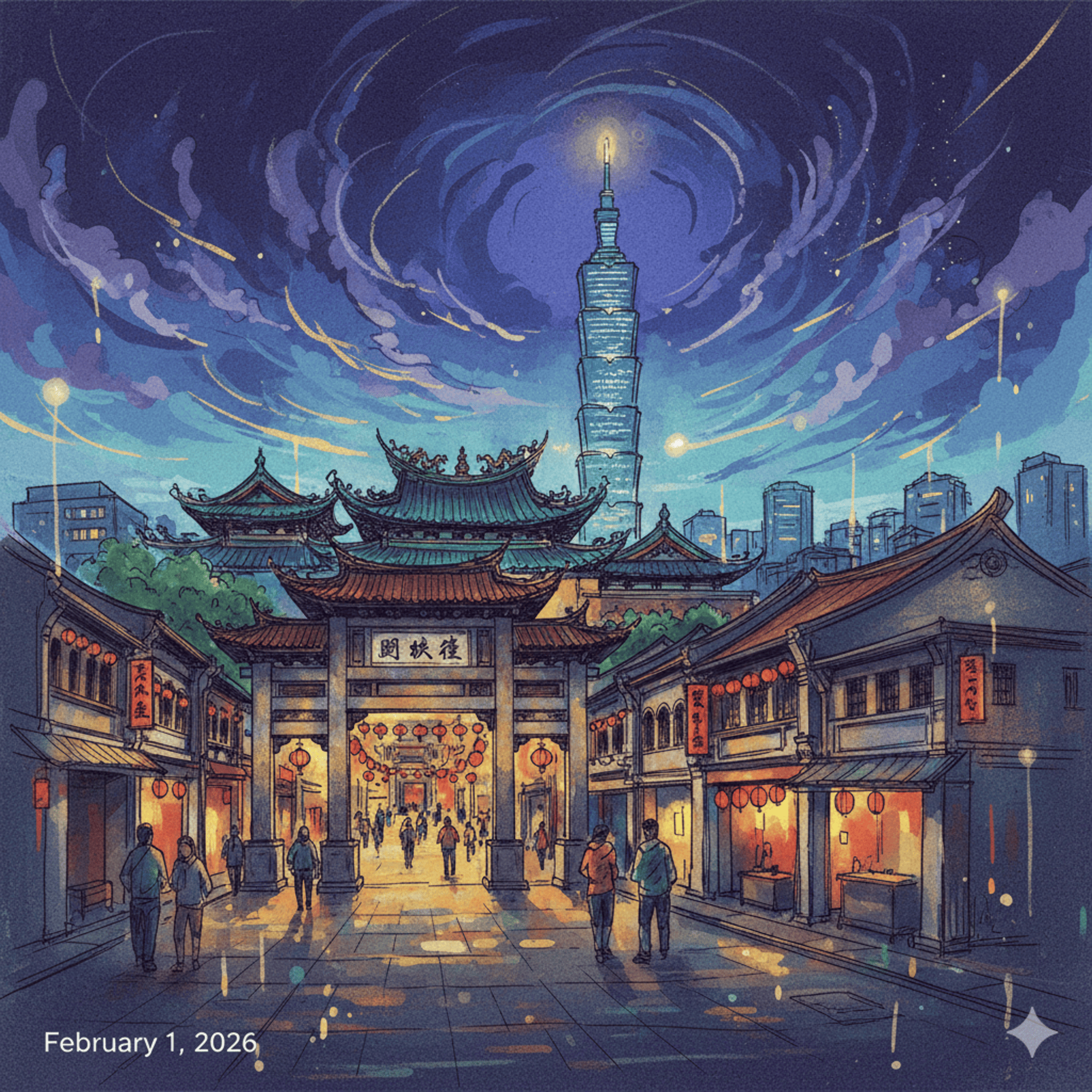

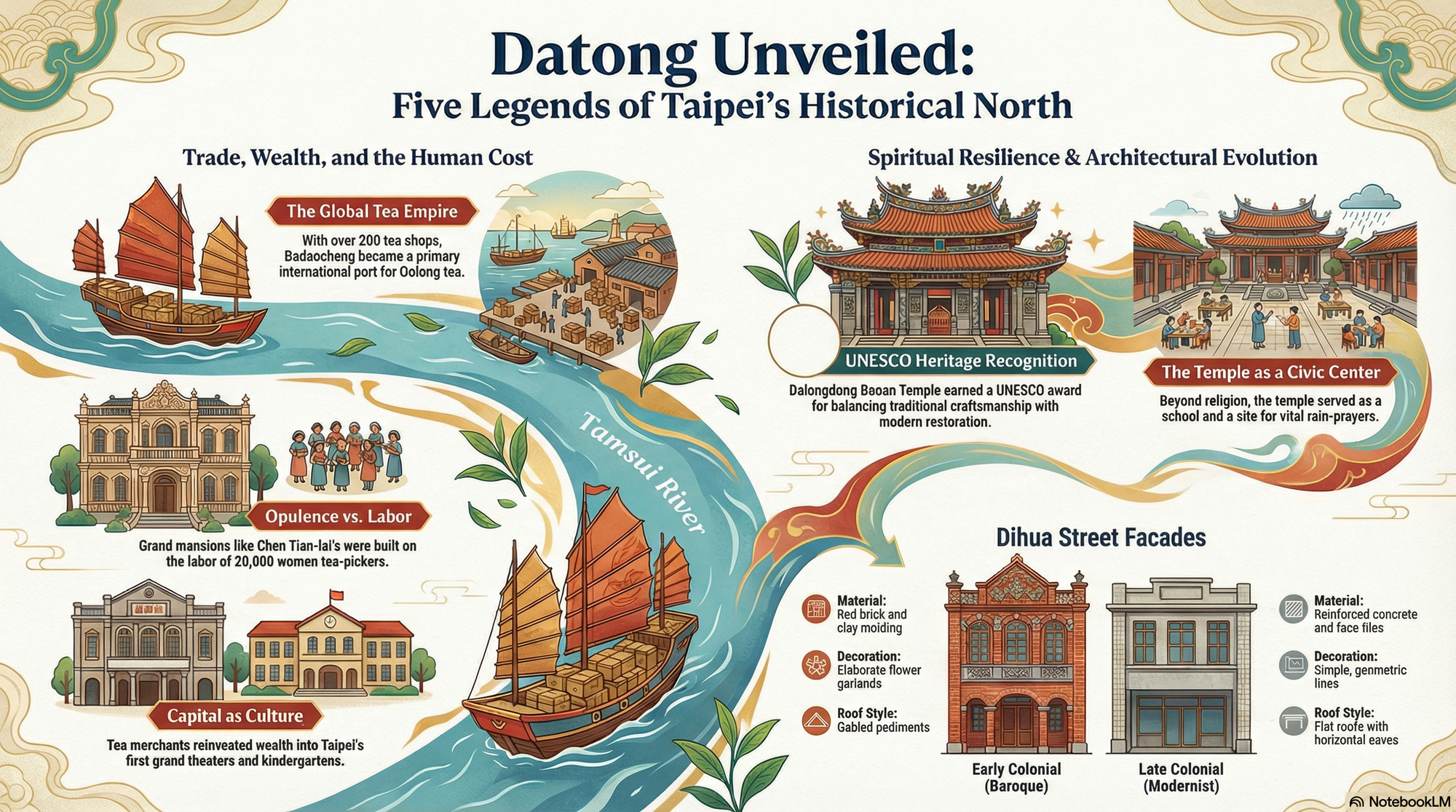

To the modern eye, Taipei is a city of soaring glass towers, humming MRT lines, and vibrant night markets. Yet, nestled in its northern corner, the Datong District holds the city’s origin story—a dense, layered history that predates the metropolis we know today. This is Taipei’s historical heart, a place where the city's most compelling narratives are not confined to museums but are etched directly into the architecture, alleys, and riverbanks. The stories of global trade that reshaped a coastline, the hidden labor that funded an empire, and the cultural resilience that outlasted colonial rule are all here, waiting to be discovered on foot. This guide uncovers five of these surprising histories, revealing how the streets of Old Taipei are a living document of its remarkable past.

How a "Blind Gut Harbor" Became Taipei's Gateway to the World

A city’s destiny is often assumed to be a product of its geography—a deep harbor, a strategic mountain pass, a fertile plain. But the story of Dadaocheng’s port reveals how profoundly human policy can rewrite that destiny, turning a geographical afterthought into an international powerhouse.

Originally, the waterway that would define Dadaocheng was an unremarkable secondary branch of the Keelung River. Local residents gave it the unflattering name 盲腸港仔 (mángcháng gǎng zǐ, or “Blind Gut Harbor”), a term that perfectly captured its peripheral status. For decades, the main commercial artery of Northern Taiwan was the port at Monga, located upstream. However, Dadaocheng’s fate was dramatically reversed by two converging forces. First, the relentless silting of the Danshui River began to choke off access to Monga, rendering it increasingly impractical for large vessels.

The decisive blow came not from nature, but from politics. In 1887, Taiwan’s first governor, Liu Ming-chuan, made a strategic decision to designate Dadaocheng as a settlement for foreign merchants. This single act of policy was a turning point. International ships and traders flocked to the once-secondary harbor, and Dadaocheng rapidly eclipsed its rival, becoming the undisputed commercial hub of the region. This transformation is a powerful lesson in how political intervention can turn a perceived weakness into a global strength.

Today, the historic Dadaocheng Wharf has been reimagined as the Yanping Riverside Park. The great cargo ships and foreign trading vessels are gone, replaced by cyclists and families enjoying the waterfront. Yet, standing on the riverbank, a visitor can still visualize this profound shift—from a bustling artery of global trade to a cherished space for modern recreation.

This strategic decision didn't just change the flow of the river; it unleashed a flow of capital that would forever reshape the city's skyline.

The Tea Tycoon Whose Mansion Was a Declaration of Power

The immense wealth generated at Dadaocheng's port during the Japanese colonial period gave rise to the "Tea Gold" era. This prosperity wasn't just about luxurious living; it became a powerful tool for Taiwanese elites to assert their cultural and economic standing on a global stage, communicating their ambition and influence through the very stones of their buildings.

No one embodied this more than the tea merchant Chen Tian-lai. His firm was one of over 200 in Dadaocheng, an area that dominated Taiwan’s lucrative tea export market. To showcase his success, Chen built an opulent residence on Guide Street in the 1920s. From its rear balcony, he could gaze out at the ships at the Danshui River wharf, a constant reminder of his commercial dominion. The three-story,仿Baroque (imitation Baroque) mansion was a spectacle of Western architectural language, featuring a symmetrical design, grand archways, and a mix of classical columns from Doric to ornate Corinthian.

The architecture was far more than decoration; it was a strategic performance. This was a "skillful use and exaggerated expression" of European styles, a material proof of his status designed to communicate with Western traders.

The mansion was more than a home; it was a statement. By adopting and masterfully exaggerating European architectural styles, Taiwanese capitalists on Guide Street were asserting their equal standing on the international stage.

Chen's influence extended well beyond commerce. He astutely invested his profits into cultural institutions, founding the Yongle-za and Dai-ichi Gekijo theaters. This was not mere philanthropy; it was a strategic move to control the city's elite social life. By owning the premier venues for entertainment, Dadaocheng’s tea tycoons established a cultural dominance that mirrored their economic power.

Today, the Chen Tian-lai Residence is a designated historic site, currently undergoing renovation. For a more accessible glimpse into this era, visitors can explore the 新芳春茶行 (Xinfangchun Tea House), a magnificently preserved tea house that now serves as a museum, offering a tangible connection to the age of Tea Gold.

But the glittering facades of these mansions cast long shadows, obscuring the story of the labor that made it all possible.

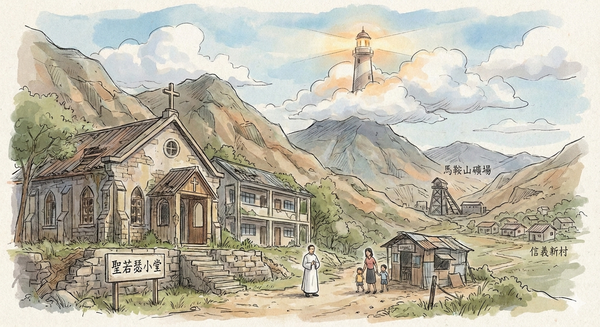

The Temple That Became a City's Unofficial Government

We often think of a temple as a place of quiet worship, set apart from the secular world. But in the turbulent decades of the early Japanese colonial period, the 大龍峒保安宮 (Dalongdong Baoan Temple) evolved into something more: a vital civic institution that provided social stability, cultural continuity, and administrative leadership when official structures were either absent or mistrusted.

The temple’s role in the community transcended religion. It served as a temporary school, becoming the predecessor to today’s Dalong Elementary School, and even housed a 製莚會社 (a company for making woven mats) that trained women in valuable skills. More remarkably, before Taipei’s official Confucius Temple was completed, the Baoan Temple stepped in to host the city’s official Confucian ceremonies in 1926 and 1927. It also led crucial rain-praying rituals during periods of drought—a vital function in what was still a largely agricultural society. In these ways, the temple acted as a de facto "civic center," using its deep-rooted community trust to maintain social order and preserve cultural heritage.

This deep connection is reflected in its founding legend of the "two ancestor" statues of the deity Baosheng Dadi. The smaller statue arrived swiftly, symbolizing the immigrants' urgent need for divine protection. The larger "second ancestor" statue, however, was delayed by a storm and took months to travel overland. Its slow, celebrated journey symbolizes the faith's process of diffusion, establishing a ritualistic identity, and becoming widely accepted by communities across the island.

This historical importance has been recognized on a global scale. In 2003, the temple's meticulous restoration project was awarded the prestigious UNESCO Asia-Pacific Heritage Award for Culture Heritage Conservation. The award celebrated its success in blending modern scientific preservation techniques with traditional craftsmanship, turning the temple into a living textbook for cultural heritage. A visit today is a chance to see a world-class example of how history can be preserved with both reverence and innovation.

While institutions like the Baoan Temple anchored the community's spirit, the city's economic engine was powered by a workforce whose stories were rarely carved in stone.

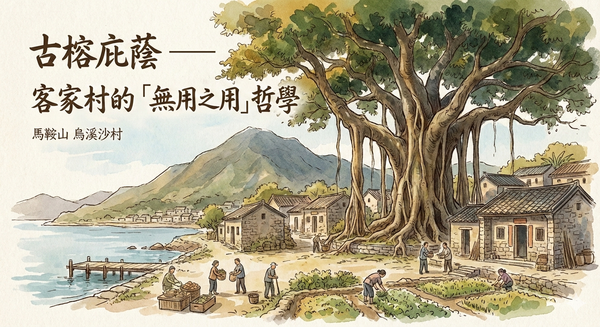

The Hidden Workforce: How 20,000 Women Powered Taipei's Golden Age

The story of Dadaocheng's prosperity is traditionally told through the lens of wealthy tea merchants and their magnificent mansions. But this narrative is incomplete. The "Tea Gold" that funded their empires was refined by the hands of a massive, hidden workforce: tens of thousands of women whose labor was the true engine of the era.

On an average day during the bustling tea season, an estimated 20,000 female tea pickers, or 撿茶女 (jiǎn chá nǚ), would gather in Dadaocheng. They sat for hours under the covered arcades, known as 亭仔腳 (tíng zǐ jiǎo), meticulously sorting through piles of raw tea leaves. Their painstaking work—removing stems, impurities, and damaged leaves—was the crucial final step that ensured the high quality required for export.

The conditions were harsh. Reports from the era describe women being forced to work until they had sorted a full quota, and some sources even mention tea house employees using bamboo sticks to threaten women into working. This history reveals a stark structural inequality. The opulence of Chen Tian-lai's residence on Guide Street was built on the "blood and sweat" of women working just streets away.

The story of Dadaocheng is one of two extremes: the public glory of Baroque mansions on Guide Street and the hidden toil of thousands of women in the arcades below. One could not exist without the other.

To reconnect with this forgotten history, modern visitors can join a "女路走讀" (Women's Path walking tour), an exploration that recenters the city’s narrative on its female figures. A key landmark is the 永樂布業商場 (Yongle Fabric Market). As Taiwan’s premier center for textiles, it stands as a spiritual successor to the tea-picking era—a vibrant commercial hub that continues to thrive on industries and crafts traditionally associated with women, and a powerful reminder of their enduring legacy.

The legacy of these women is woven into the district's commercial fabric, just as the city's changing fortunes are visible in the very architecture of its streets.

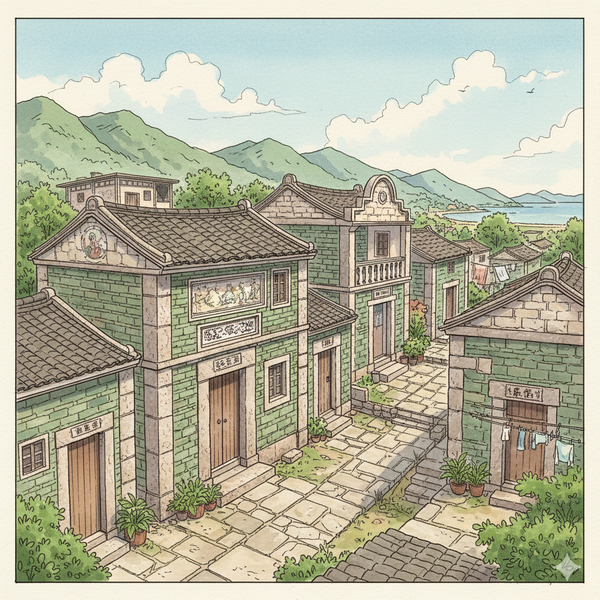

How an Earthquake in Tokyo Reshaped Taipei's Architecture

The iconic shophouse facades, or 牌樓厝 (páilóu cuò), of Dihua Street are not static relics. Instead, they form a dynamic architectural timeline, a physical record of a city responding to colonial policy, global trends, and even a natural disaster hundreds of miles away.

Their evolution was driven by the Japanese "Urban Improvement Plan," which required property owners to build new street-facing fronts. However, the colonial government's policy for Taiwanese districts was to "regulate, but don't design," giving local craftsmen the freedom to create a unique cultural compromise. This resulted in two distinct phases.

The first phase, during the early Japanese period, was dominated by an ornate, 仿Baroque style. Reflecting the peak of the tea trade’s wealth, these facades were characterized by complex floral decorations and romantic arched windows.

By the 1920s, a dramatic shift occurred toward a cleaner, more functional Modernist style. This was not merely a change in taste. The key driver was the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 in Tokyo. Learning from the disaster, which flattened many heavy, ornate brick buildings, architects in Taipei adopted modern engineering principles. This "rapid, mature reaction" shows a city closely connected to global modern thought, choosing structurally sound, less top-heavy materials like reinforced concrete.

This pragmatic evolution created the unique architectural blend visible on Dihua Street today.

Feature | 仿Baroque Style (Early Period) | Modernist Style (Later Period) |

Core Philosophy | Ornate, decorative, romantic expression of wealth | Functional, pragmatic, focused on structural safety |

Primary Material | Brick, with reinforced concrete to strengthen openings | Reinforced concrete, often with light-colored tiles |

Key Elements | Complex floral carvings, arched windows, elaborate facades | Clean lines, flat roofs, horizontal eaves |

Today, a walk down Dihua Street is a tour through a "living museum of architectural evolution." The revitalization of these buildings, such as the Starbucks on Bao'an Street housed in a century-old structure, proves this history remains a vital part of the modern city. For those interested, more information can be found in articles on the history of Dadaocheng neighborhoods.

This architectural timeline provides a final, powerful lesson: that the story of a city is one of constant adaptation, resilience, and change.

Reading the Layers of a Living City

The five stories of Datong District reveal that its history is not a single narrative but a series of interwoven layers—of geography, capital, faith, labor, and design. But looking closer, we see a powerful philosophy of resilience. When the tea trade faded, the district did not crumble; its value was preserved in its architecture and its stories, which have become a new kind of cultural currency.

This preservation is more than an act of nostalgia; it is a strategy that provides cultural and spiritual resilience against the inevitable fluctuations of time. As observers of this history, we have a responsibility to look beyond the "successful man's history" of tycoons and their mansions. We must also seek out the stories in the shadows—the forgotten labor of the 撿茶女 in the arcades, whose toil made the glory possible. To walk these streets is to practice a more critical and engaging form of observation, achieving a small measure of social justice by acknowledging the complete story.

The next time you walk through an old city, ask yourself: what stories are hidden in plain sight, and whose voices have yet to be heard? To continue exploring the rich history of Taiwan's capital, consider reading our other historical travel guide to Taipei, by subscribing this website.

References

- 臺北市大同區公所-大稻埕街屋之演變, accessed on November 21, 2025

- 臺北市大同區公所-歷史沿革, accessed on November 21, 2025

- 大稻埕 - 台灣光華雜誌, accessed on November 21, 2025

- 永樂市場- 陳天來故居/錦記茶行、大稻埕碼頭 - udn部落格, accessed on November 21, 2025

- 李春生紀念教會週邊景點 - 台北旅遊網, accessed on November 21, 2025

- 陳天來故居(錦記茶行) - 台灣旅圖, accessed on November 21, 2025

- 陳天來故居 - 山富旅遊, accessed on November 21, 2025

- 新芳春茶行 - 博物之島- 文化部, accessed on November 21, 2025

- 大龍峒保安宮 - DalongDong Baoan Temple, accessed on November 21, 2025

- 正體中文 - 大龍峒保安宮, accessed on November 21, 2025

- 臺北舊城時光~大稻埕的前世今生 - 社團法人中華民國自然步道協會, accessed on November 21, 2025

- 大稻埕女性空間的移動 - 台灣國家婦女館, accessed on November 21, 2025

- 永樂布業商場_永樂市場 - 臺北旅遊網, accessed on November 21, 2025

- 大稻埕街區_迪化街店屋- 台北 - 臺北旅遊網, accessed on November 21, 2025

- 生活- 新芳春茶行見證大稻埕榮景 - 青年日報, accessed on November 21, 2025

- 宗教百景,臺北大龍峒保安宮accessed on November 21, 2025

- 大龍峒保安宮, UNESCO資產保存獎, accessed on November 21, 2025

- 敏迪散步:歡迎回到1930年的台北「大稻埕」 - 翻轉教育- 親子天下, accessed on November 21, 2025