(ENG) The Resilient Soul of Osaka: Five Layers of History in Nishinari-ku

Layered history of Nishinari-ku, from its labor-market origins and Taisho architecture to its modern artistic rebirth and culinary soul food.

Can a daily-wage labor hub transform into a global backpacker paradise?

What cultural role does Tobita Shinchi play in Taisho romantic architecture and legal evasion?

How can art be a force for community regeneration and against social labels?

To understand the neon-soaked skyline of modern Osaka, one must look toward its geological and sociological foundations. Nishinari-ku, often relegated to the shadows of travel guides, is the essential bedrock upon which the city’s identity was forged. It was here, in the yoseba—the gathering places for day laborers—that the physical muscle of the Japanese economic miracle was recruited and housed. There is a profound tension in these streets; Nishinari is a marginal space, yes, but it is also a repository of an authentic urban resilience that refuses to be sanitized. To step onto the weathered pavement of the west side is to leave the curated path of the "tourist Japan" and confront the unvarnished history of those who built the nation from the ground up.

Listen to the historical stories told in detail (For subscribers only)

The Cradle of Labor: From Yoseba to the Global Backpacker Hub

The spatial identity of Kamagasaki, the heart of Nishinari, was molded by the relentless demands of industrialization. Its transformation began in earnest following the 1903 Domestic Industrial Exhibition and accelerated during the post-war reconstruction. As a massive influx of laborers arrived to rebuild a shattered nation, Kamagasaki became Japan’s largest labor market—a "last line of defense" for the unemployed, the family-displaced, and those newly released from prison.

The term doya, synonymous with the district’s cramped lodgings, is a poignant linguistic reversal of yado (inn). By flipping the word, the residents signaled that these were not traditional guest houses but minimalist, ultra-cheap shelters. These structures required no identification or deposit, offering a raw pragmatism that defined the neighborhood for decades. Interestingly, this historical infrastructure of "minimalist efficiency" has found a second life in the wake of the 1991 bubble burst. The doya architecture proved perfectly suited for the modern global budget traveler. Sites like Matsu Guest House stand as modern manifestations of this history, offering an affordable spirit that maintains the district’s tradition of accessibility. In this transition, the arrival of international travelers has begun to dilute old stigmas, breathing new life into the historic "floating homes" of the working class.

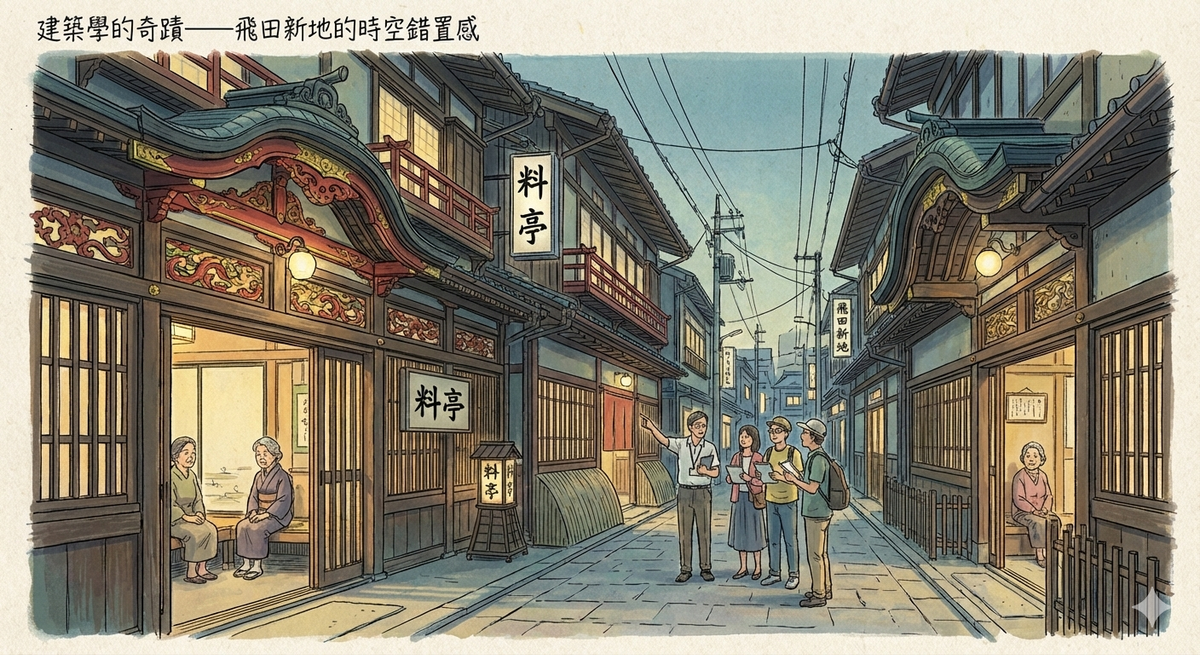

The Architecture of the Ephemeral: The Frozen Time of Tobita Shinchi

While much of Osaka was leveled during the firebombings of World War II, the Tobita Shinchi district emerged as a strategic historical miracle. Its survival left an architectural enclave that feels frozen in time, though its origins are darker than the polished wood suggests. Built upon a former execution ground and a sprawling cemetery, the district’s Taisho-era aesthetic was born from a soil already steeped in the ephemeral.

Following the 1958 Prostitution Prevention Law, the district navigated a masterclass in "Legal Pretension." The brothels famously closed for a single night, only to reopen the next day as ryoutei (Japanese restaurants). This social contract allowed the physical structures to remain intact, preserving the "Taisho Roman" style that has vanished elsewhere. The architecture here is a departure from traditional Japanese minimalism; instead, it is a flamboyant theater of intricate wood carvings and motifs mimicking temples, bridges, and docks. For the traveler, a Historical Architectural Walking Tour focusing on these murals and carvings offers a rare glimpse into a "living fossil" of social and legal negotiation. It is a space where visual luxury remains functional only through a veil of institutionalized pretense.

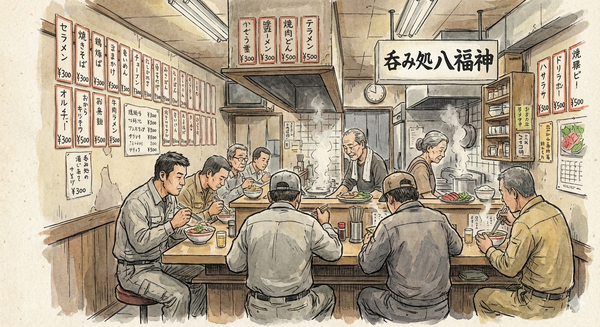

The 1,000-Yen Philosophy: Gastronomy of the Working Class

The visual extravagance of Taisho-era facades soon gives way to a more visceral hunger, leading us from the eyes to the gut. The culinary soul of Nishinari was birthed in the "quick, filling, cheap" mandate of the 1950s black markets. This was survival gastronomy, designed for laborers who needed maximum calories on a razor-thin budget. This economic reality birthed a "hardcore" version of Osaka’s soul food that persists today, untouched by the inflation of the city center.

The "1,000-yen philosophy" is not merely a bargain; it is a historical artifact—a pricing floor established by the daily wage of a laborer. In the raw, un-curated theater of a Nishinari food stall, a full meal and a drink still rarely exceed a thousand yen. While establishments like Nomidokoro Hachifukujin may lack standardized tourist service, their lack of a "filter" is a testament to the district’s unyielding character. Here, the authenticity lies in the lack of performance; the food is a direct link to the survival habits of the post-war era.

Artistic Redemption: The Murmurs of the Street

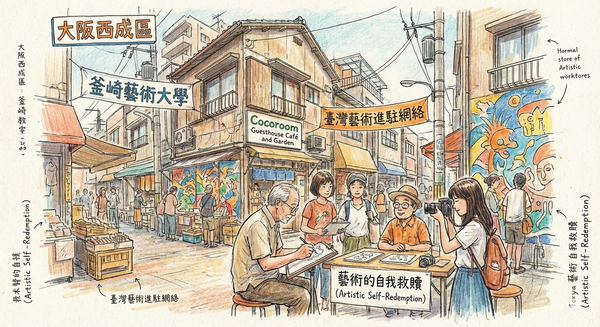

For decades, the stories of Nishinari were told through the "low whispers" of 1960s folk music. Songs like Kamagasaki Ninjō documented the hardships of the doya-gai with a melancholic pride. Today, that impulse for expression has evolved from recording struggle to facilitating rescue. Under the guidance of poet Ueda Kanayo, projects such as Cocoroom and the Kamagasaki University of the Arts have sought to provide a counter-narrative to the stigma of the "slum."

These spaces are not merely galleries; they are platforms for psychological rehabilitation for a community long ignored by the state. By turning the district from a "social problem" into a "cultural solution," these art spaces empower residents to reclaim their own stories. The Cocoroom Guesthouse Café and Garden serves as a vital node for this movement, attracting international artists and linking Nishinari’s local struggles to a global conversation about community and the right to exist.

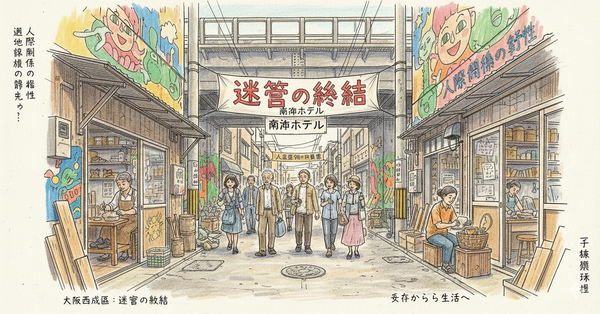

Beyond the Labyrinth: The Evolution of the "Nankai Hotel"

In the 1950s, the area behind the main roads was a claustrophobic, soot-stained labyrinth of shantytowns. The most famous symbol of this era was the "Nankai Hotel"—a name born of the biting, desperate black humor of the residents. It referred to the makeshift shelters built directly under the Nankai Railway overpass, where people survived by shoe-shining, scavenging, or selling scraps.

Today, this irony has been replaced by a new kind of vitality. While the shanties are gone, the spatial continuity of the narrow alleys remains. These former sites of desperate survival now host vibrant street art and independent workshops. The transition from "survival" to "living" is palpable in the unnamed back-alley workshops and murals that now redefine the old spatial labels of the district. The resilience of human relationships here—characterized by a warmth that subverts the area’s "dangerous" reputation—suggests that the spirit of the old labyrinth has matured into a unique form of community pride.

The Layered Observation of Nishinari

Nishinari-ku is a testament to the fact that a city’s most fragile areas are often its most truthful. To observe Osaka only through its highlights—its neon towers and pristine temples—is to read only the final chapter of a very long book. Nishinari provides the preceding chapters: the sweat, the struggle, and the unyielding resilience that made the modern city possible.

Understanding these five layers of history requires a willingness to look at the grit without seeking to "clean it up." When we modernize and sanitize our urban environments, we often lose the very history that gives a city its soul. Nishinari stands as a reminder that even in the shadows of progress, life persists with a fierce, creative energy. What is lost when we finally "fix" the neighborhoods that refused to break?

For more deep-dives into the hidden shadows of the world’s great cities, we invite you to subscribe to Lawrence Travel Stories.

Logistics & Practical Information

- How to Get There: Access the district via Shin-Imamiya Station (JR and Nankai lines) or Dobutsuen-mae Station (Osaka Metro Midosuji and Sakaisuji lines).

- Recommended Accommodation: Experience the evolution of the doya at Matsu Guest House, a high-value hostel that bridges the gap between the neighborhood's history and its future as a global traveler hub.

- Nearby Explorations: For a study in contrasts, take the "transition walk" from the narrow alleys of Nishinari to the soaring heights of Abeno Harukas, observing how the old foundation of the city supports its newest heights.

References

- 西成區| 預訂至抵酒店每晚低至[MINPRICE] - Agoda, 檢索日期:10月 11, 2025

- Kamagasaki: Renewing an Urban Poor Community - ヒューライツ大阪, 檢索日期:10月 11, 2025

- The History of Kamagasaki :After 1945, 檢索日期:10月 11, 2025

- Skid Row, Yokohama: Homelessness and Welfare in Japan | Nippon.com, 檢索日期:10月 11, 2025

- Tobita Shinchi - Wikipedia, 檢索日期:10月 11, 2025

- Tobita Shinchi - Osaka - Japan Experience, 檢索日期:10月 11, 2025

- Osaka: Historical Red Light District and Ghetto Walking Tour | The Abroad Guide, 檢索日期:10月 11, 2025

- 呑み処八福神 大阪自由行西成區不到一千日圓的美味午餐 - 鄉民食堂, 檢索日期:10月 11, 2025

- Isolation and Neighboring Relations in Osaka's Kamagasaki: The Gaps and What Breaks Through Them. To Express is to Live – FIELD, 檢索日期:10月 11, 2025

- 浪花藝術空間- Arts Residency Network Taiwan 藝術進駐網 - 文化部, 檢索日期:10月 11, 2025