(ENG) The Weaver, The Monk, and The Warrior: Higashinari-ku, Osaka

Higashinari-ku is not a postcard, but a living document where layers of history—sacred duty, personal grief, mythic transformation, industrial grit, and modern serenity—all coexist.

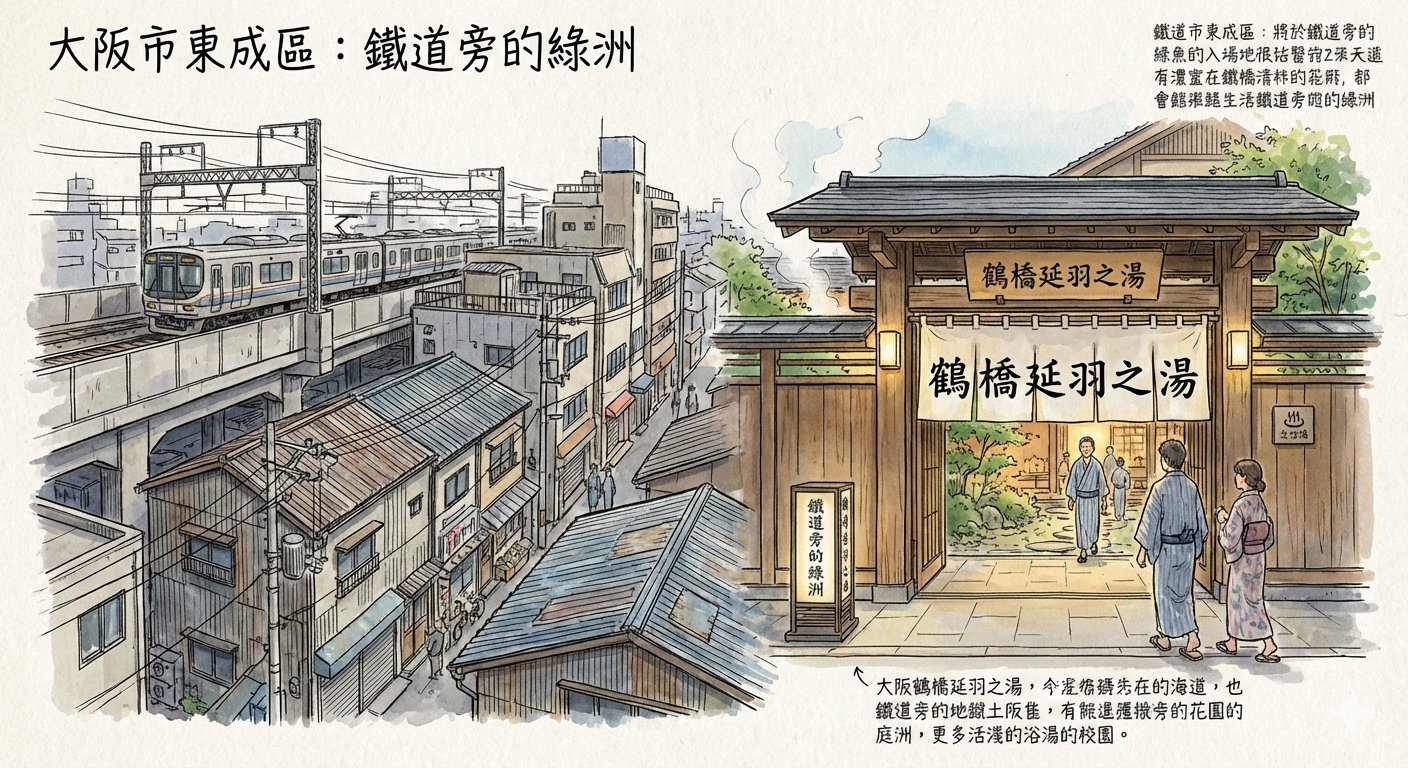

鶴橋延羽之湯 Nobeha No Yu Tsuruhashi > 清原院法妙寺與雁塚石塔 Ganzuka stone pagoda of Kiyohara-in Homyō-ji Temple

Listen attentively to the historical stories told in detail

Beyond the Neon Glow

When we picture Osaka, the mind conjures a kinetic landscape of dazzling neon, towering commercial fortresses, and rivers of people flowing through canyons of commerce. It is a city of immense energy, a celebrated "Kitchen of the Nation." Yet for the modern traveler, a hunger for something more authentic, more unpolished, is growing. There is a desire to look past the brilliant facade and find the city's unfiltered soul—the places where history is not curated in a museum but lived in the quiet alleys and workshops.

This is where you find Higashinari-ku. Tucked into Osaka's eastern flank, it is not a destination of grand tourist monuments. Instead, it is a historical corridor, a dense and industrious ward where the true character of the city has been forged over millennia. From sacred imperial rituals and profound medieval philosophy to the gritty tenacity of its factory workers, Higashinari offers a narrative far richer than any guidebook. Here are five stories that reveal the soul of Osaka, hidden in plain sight.

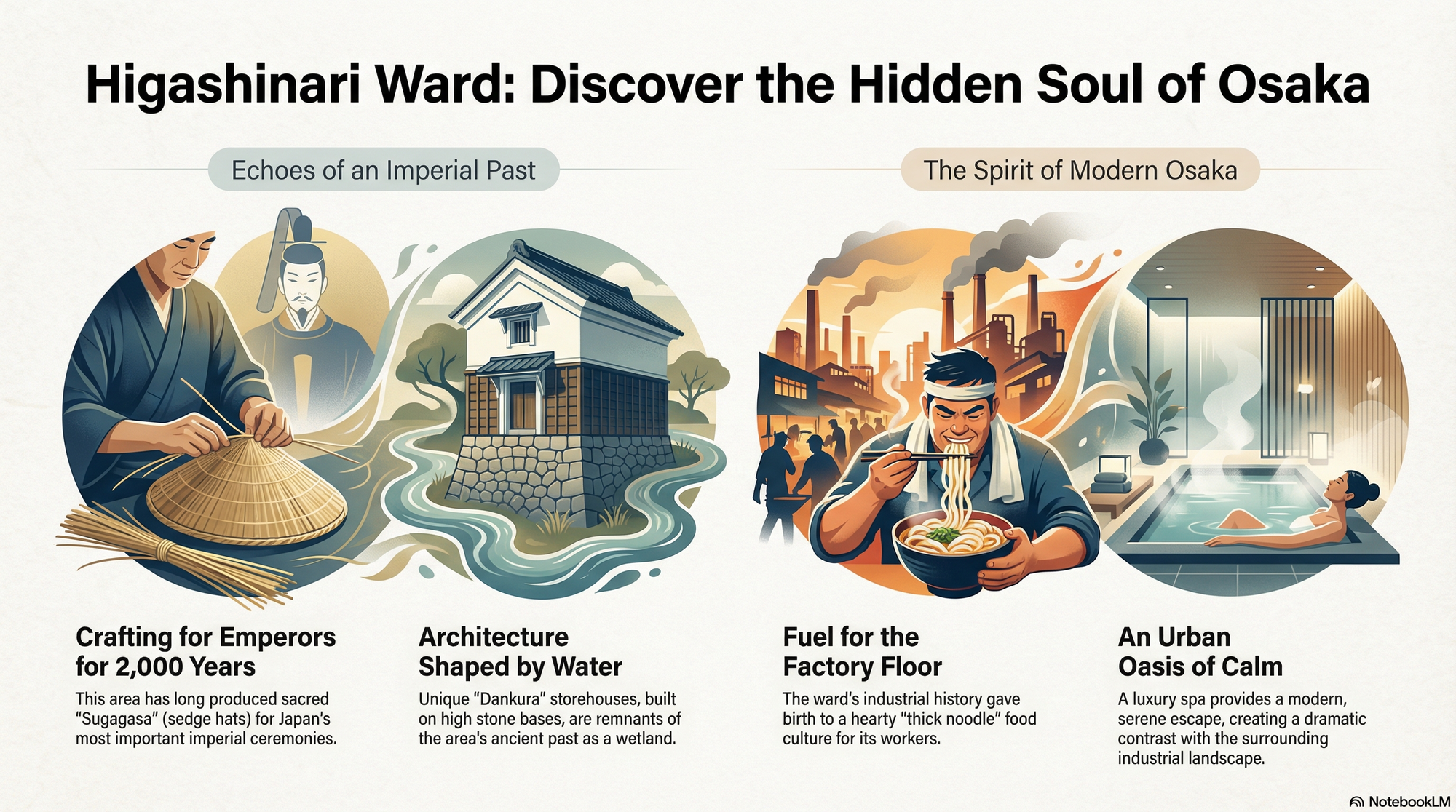

The Emperor's Crown: A 2,000-Year-Old Ritual in a Forgotten Village

In the heart of a modern industrial ward, it is almost impossible to imagine the survival of a craft so ancient and sacred that it directly serves the Emperor of Japan. Yet, the history of Higashinari begins not with factories, but with an imperial duty born from the very land itself.

The Fukae area was once a low-lying, swampy island whose geography made it ideal for growing the finest sedge grass. Recognizing its immense value some 2,000 years ago, a group of master artisans from the established "Kas縫邑" (Village of Hat Weavers) in Yamato, modern-day Nara, migrated to this island to secure a supply of this essential material. Here, they dedicated themselves to a singular, sacred purpose: crafting the Sugagasa, or sedge hats.

These were not common head coverings. The Sugagasa from Fukae were—and still are—sacred objects essential to Japan's highest rituals. They are supplied for the Emperor's "Daijōsai," the Great New Rice Ceremony performed only once per reign, and as the "菅御笠" (Sedge Imperial Hat) for the "Shikinen Sengū" at the Ise Grand Shrine, the nation's most sacred Shinto site. This represents an unbroken, thousand-year-old spiritual thread connecting a small, unassuming neighborhood to the very heart of the empire.

In the shadow of factories, the weavers of Fukae don't just craft hats; they guard the purity of an empire's soul, stitching together the past and the present with each blade of sacred grass.

This ancient history can be touched and felt. A visit to the Fukae Inari Shrine, the old village's guardian deity, reveals a stone monument marking the site of the "Kas縫邑跡." From there, a walk through the surrounding alleys uncovers a unique architectural footprint: the Dankura. These storehouses, built on high stone foundations to protect against the floods that once defined this "water village," are tangible proof of a community that learned to thrive in a challenging landscape. Today, the local "Fukae Sugada Preservation Society" works tirelessly to restore the sedge fields, proving this sacred duty is not just a relic, but a living tradition still being fought for. From this story of collective spirit, another emerges from the depths of profound, personal solitude.

The Weeping Geese: A Medieval Monk’s Grief and a Lesson in Compassion

Moving from the grand scale of imperial ritual, Higashinari’s next story pivots to the deeply personal and universally relatable experience of suffering. It is a tale that transforms a quiet temple into a place of philosophical awakening, offering a silent counter-narrative to the bustling city outside its walls.

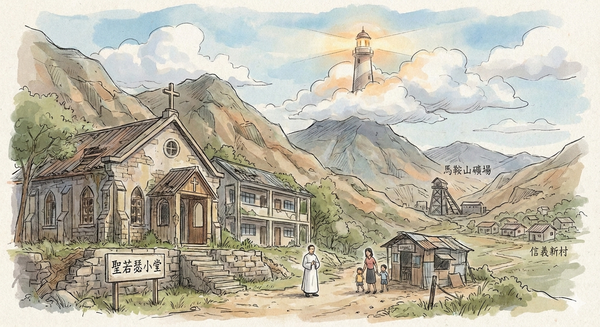

The story belongs to Homyō Shōnin, the founder of Homyō-ji Temple. As a young man, he was struck by an almost unimaginable series of tragedies when he lost his parents, wife, and children to a devastating plague. Overwhelmed by the crushing reality of impermanence, he renounced the world and dedicated his life to spiritual practice. In 1318, he founded the temple as a sanctuary for salvation.

But the temple's most poignant lesson comes from the legend of the "Ganzuka" (Wild Goose Mound). The tale recounts how Homyō's brother shot two wild geese from the sky. Witnessing the profound bond between the birds—said to be mates or parent and child—he was struck with such deep remorse for the life he had taken that he, too, became a monk.

This legend elevates the temple beyond a simple place of worship. It becomes a vessel for contemplating loss, empathy, and the interconnectedness of all living things. The story of the weeping geese asks us to consider how a moment of violence can lead to a lifetime of compassion. For the modern visitor, the Ganzuka stone pagoda, resting quietly within the grounds of Kiyohara-in Homyō-ji Temple, is a hidden gem for quiet reflection. It is a place to meditate on the eternal themes of love, loss, and forgiveness, finding a moment of spiritual clarity amid the urban density.

The Warrior God's Secret: Finding Love in Japan's First Poem

While most know the god Susanoo no Mikoto as a fierce, dragon-slaying warrior, Higashinari holds the key to his softer, more creative identity. This story reveals how a deity known for storms and calamity was transformed into a guardian of love and learning through the power of a single creative act.

At Yasaka Shrine, Susanoo no Mikoto is the main deity, but the focus is not on his famous battle with the eight-headed serpent. Instead, the shrine celebrates his role as the first-ever composer of a waka, a classical 31-syllable Japanese poem. After his victory, he sought a place to build a home with his wife and, upon finding the perfect spot, composed this verse:

八雲立つ出雲八重垣、妻籠みに八重垣作る、その八重垣を

Yakumo tatsu / Izumo yaegaki / Tsumagomi ni / Yaegaki tsukuru / Sono yaegaki wo

This poem is a joyful celebration of building a protective home for his beloved wife. This singular act of poetic creation transforms his identity. The fierce warrior becomes a god of "good fortune in matchmaking" and "marital harmony." Furthermore, this cultural creation established him as a deity of academics and learning, showing a transformation not just from warrior to husband, but from brute force to intellectual grace. This reputation is deepened by a play on words; a related term, "Kukuru," means "to bind or connect," reinforcing the shrine's power to forge strong, lasting relationships.

The hidden gem here is Yasaka Shrine itself. It is a place to seek a "perfect balance"—not just the raw courage of a warrior, but the gentle creativity and protective harmony required to build a life, a relationship, and a legacy.

The Taste of Tenacity: How Factory Work Forged Osaka's Boldest Noodles

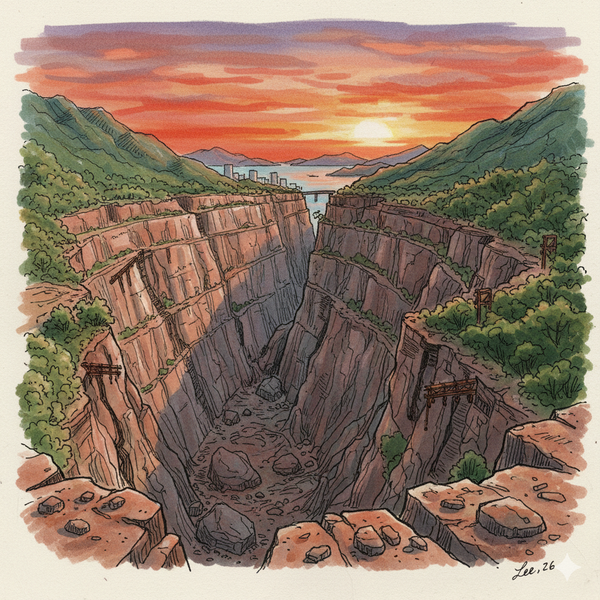

To truly understand a place, you must taste the food of its working people. Higashinari's modern identity is forged in steel and sweat; it is a core part of Osaka's eastern industrial zone, a dense landscape of small and medium-sized enterprises driven by a spirit of dedicated craftsmanship, or shokunin. This is the home of world-renowned brands like Olfa, the inventor of the snap-off blade cutter, and this industrial soul can be tasted in a bowl of its most famous noodles.

The high-intensity labor and fast pace of factory life created a demand for food that was high in calories, intensely flavorful, and could be served quickly. This environment gave birth to a unique "thick noodle culture" (futomen). These noodles were not delicate or subtle; they were robust fuel designed to power the engine of modern Osaka.

This is not food for contemplation; it is fuel for the resilient. In every bowl of dark, rich broth and thick, chewy noodles, you can taste the sweat and spirit of the people who built modern Osaka.

The most iconic expressions of this culture are Takaida-kei Ramen and the local yakisoba found in the Imazato area. Takaida-kei Ramen is famous for its distinctively thick, chewy noodles swimming in a dark soy sauce broth that, despite its rich appearance, is surprisingly refreshing. It is the authentic taste of "Shitamachi" (working-class) Osaka—a direct, delicious link to the industrial tenacity that defines the ward.

The Concrete Oasis: A Secret Spa in an Industrial Maze

The final story is the ultimate expression of Higashinari's character: a place of dramatic and surprising contrasts. In a high-density urban environment defined by a mix of factories and residences, the discovery of refined peace is both unexpected and essential.

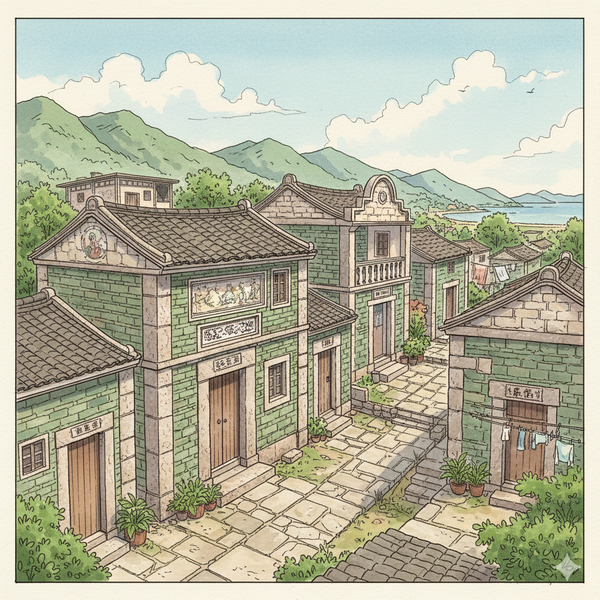

Higashinari's urban landscape is functional and unadorned. It is a place of palpable pressure, where per-capita park space is just 1.07 square meters, far below the Osaka city average of 3.52. This hard data makes the need for an oasis undeniable, and it is precisely this context that makes the existence of Nobeha No Yu Tsuruhashi so remarkable. It is not just a neighborhood public bath (sento); it is a luxurious, meticulously designed "health spa resort" that exists in stark, beautiful opposition to its surroundings.

The power of the experience is rooted in this juxtaposition. To step from the gritty, industrious streets into an atmosphere of serene, high-end service—where staff in elegant yukata attend to every detail—is to experience a "micro-vacation" from the city itself. The contrast between the ward's unpolished exterior and the spa's purifying interior elevates the sense of escape and renewal.

The final hidden gem, Nobeha No Yu Tsuruhashi, is the perfect conclusion to a day spent exploring Higashinari's deep history. It is a place to physically and mentally purify, allowing the stories of weavers, monks, gods, and workers to settle as you soak in the restorative waters.

The Soul in the Overlooked

Together, these five stories reveal a profound truth about travel and discovery. Higashinari-ku is not a postcard, but a living document where layers of history—sacred duty, personal grief, mythic transformation, industrial grit, and modern serenity—all coexist. It teaches us that the truest "hidden gems" are not geographically hard-to-reach places, but corners of the city whose immense value has been forgotten or simply underestimated by the mainstream narrative.

What forgotten stories are waiting to be found in the overlooked corridors of your own world?