(ENG) Oji-machi: A Five-Fold Palimpsest of Tokyo’s Sacred and Industrial Evolution

Oji-machi, Shinto tradition meets Meiji industry. Discover Shibusawa Eiichi’s legacy, the Fox Parade, and the nostalgic Toden Arakawa streetcar.

How does Oji balance ancient Shinto roots with industrial modernization?

What Shibusawa Eiichi's influence on Oji's cultural landmarks?

What unique local traditions and folklore define the Oji area?

In the unassuming northern quadrant of Tokyo lies Oji-machi, a district where the temporal layers of the city are not merely preserved but superimposed. This is a geographic palimpsest—a site where Edo-period pleasure grounds became the physical laboratory for Japan’s leap into modernity. To walk through Oji is to interrogate the urban fabric where Shinto spiritual authority, Meiji industrial vanguardism, and Taisho-era diplomacy intersect at the heights of Asukayama. This exploration follows five distinct movements: the sacred migration of deities, the white smoke of modern industry, the private salons of global power, the democratic rhythms of the streetcar, and the enduring shadows of folk myth. For the intellectually curious traveler, Oji offers a rare, concentrated lens through which to observe the symphony of contradictions that defines the Japanese soul.

Listen to the historical stories told in detail (For subscribers only)

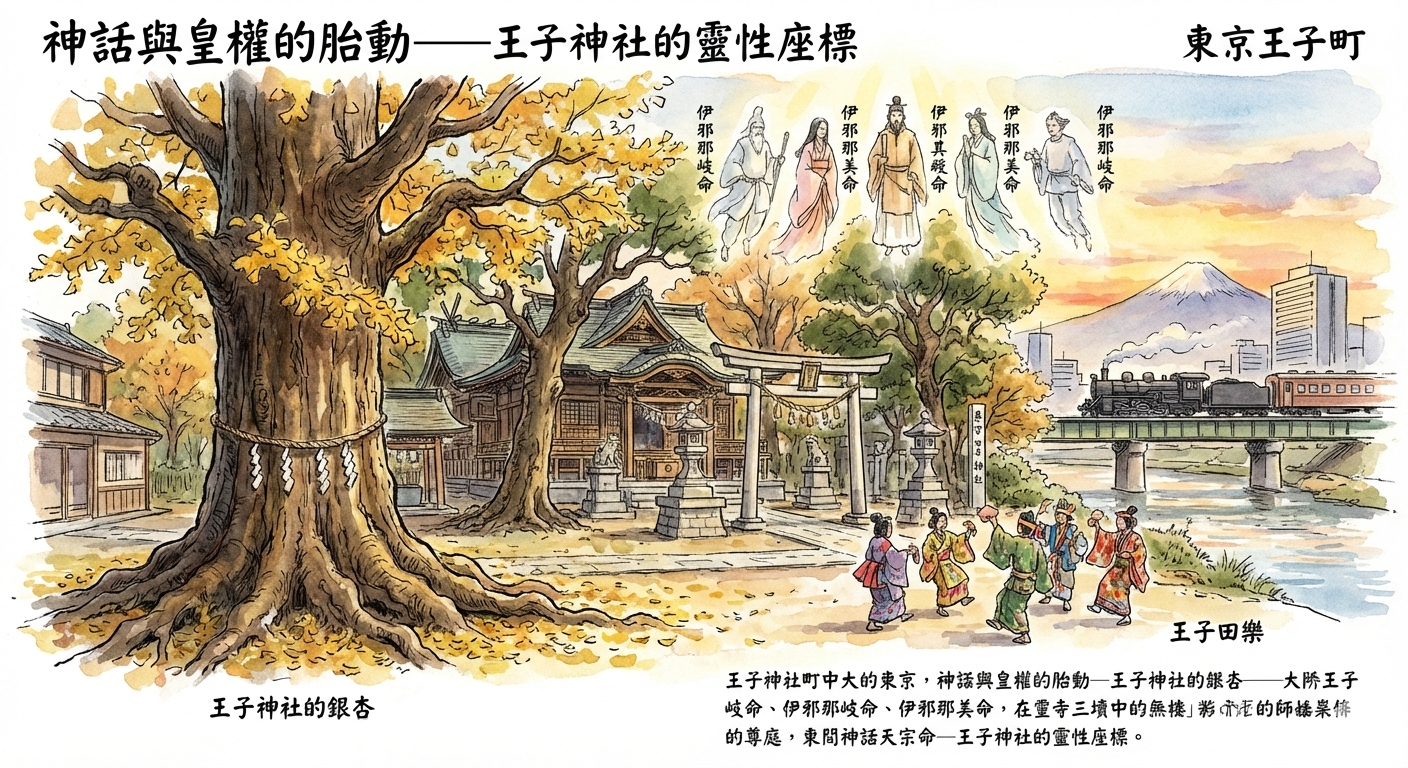

The Sacred Migration: Oji Shrine and the Eastern Shift of Deities

The historical weight of Oji-machi originates with a calculated act of religious transplantation. In early Tokyo, the establishment of spiritual authority was a deliberate cartographic exercise, and Oji Shrine stands as the preeminent result. By importing the "Prince" deity—a branch spirit from the prestigious Kumano Sanzan faith of Kii Province—the ruling powers effectively anchored the remote sacredness of the south into the heart of the eastern capital, establishing a spiritual bedrock for the Kanto region.

The shrine’s spiritual architecture is defined by a formidable five-pillar deity structure. It enshrines Izanagi-no-mikoto, Izanami-no-mikoto, Amaterasu Omikami, Hayatama-no-o-no-mikoto, and Koto-saka-no-o-no-mikoto. This assembly, representing the core creators of Japan and the Kumano lineage, granted Oji an elite status that transcended local worship. This prestige eventually culminated in its designation as a Jun-chokusai-sha (semi-imperial shrine), securing its modern role as one of the esteemed "Tokyo Ten Shrines."

"The Oji Shrine’s status as one of the 'Tokyo Ten Shrines' makes it an essential station in any religious pilgrimage, lending the travel route a sense of ritual and deep religious background."

Beneath the official designations lie living witnesses to the centuries. The Ancient Ginkgo Tree, a Metropolitan Cultural Property, stands as a silent, arboreal observer of the district's radical transformations. Complementing this is the Oji Dengaku dance, a Kita City Cultural Property, which provides a vital intangible link to the community's ancestral rhythms. These sacred foundations provided the stability required for Oji to survive the seismic shifts of the Meiji Restoration, where the tolling of temple bells would soon be joined by the hiss of steam.

The Smoke of Civilization: Shibusawa Eiichi’s Industrial Vanguard

Following the Meiji Restoration, Oji-machi served as the physical laboratory for Bunmei Kaika (Civilization and Enlightenment). Central to this movement was Shibusawa Eiichi, the "father of Japanese capitalism," who identified paper as the "vessel of knowledge" essential for a modernizing nation. In 1875, Shibusawa established the Shōshi Kaisha (later Oji Paper), strategically selecting the site for its abundant water resources.

The factory was a technological marvel, constructed by the 26-year-old British expert Frank Cheeseman. Its red-brick structure and the persistent "white smoke" from its chimneys became iconic symbols of progress, immortalized in Meiji-era ukiyo-e prints by artists like Hiroshige III. These prints captured a striking visual juxtaposition: the delicate cherry blossoms of Asukayama framed against the coal-fired industry below. This industrial achievement was so profound that it commanded visits from Emperor Meiji and the Empress, solidifying Oji’s role in the national narrative of progress.

Today, the Paper Museum in Asukayama Park stands as a monument to this era. Far from a mere display of machinery, it serves as a testament to the democratization of knowledge. By enabling the mass production of the printed word, Oji’s mills effectively fueled the intellectual rise of the Japanese public. Yet, as the industrial smoke of the lowlands signaled a new dawn, the focus shifted to the verdant heights of Asukayama, where the masters of these mills sought a different kind of progress: the refinement of the mind and the state.

The Sage’s Retreat: Diplomacy and "Taisho Romance" on Asukayama

While the mills hummed below, the heights of Asukayama became a site of unofficial international diplomacy. Shibusawa Eiichi chose this location for his residence, Aiisunsou, which spanned a sprawling 28,000 square meters. The estate evolved into a high-level financial and diplomatic salon where global leaders met to navigate Japan's entry onto the world stage.

Though much of the residence was destroyed in 1945, two National Important Cultural Properties survive as exquisite examples of "Taisho Romance" architecture—a style defined by the harmonious fusion of Western and Japanese aesthetics.

- Bankoro: This small guest pavilion, used for receiving dignitaries, features intricate woodwork and a quiet elegance that reflects the private side of public power.

- Seien Bunko: A stunning library and salon that served as a hub for intellectual exchange. Its architectural texture is rich with stained glass and detailed craftsmanship, embodying the sophisticated internationalism of the early 20th century.

For the modern traveler, these structures represent the bridge between private success and public responsibility. They offer a rare opportunity to step inside the rooms where the blueprints for modern Japan were debated, before descending from these elite heights to the tracks that carried the common man.

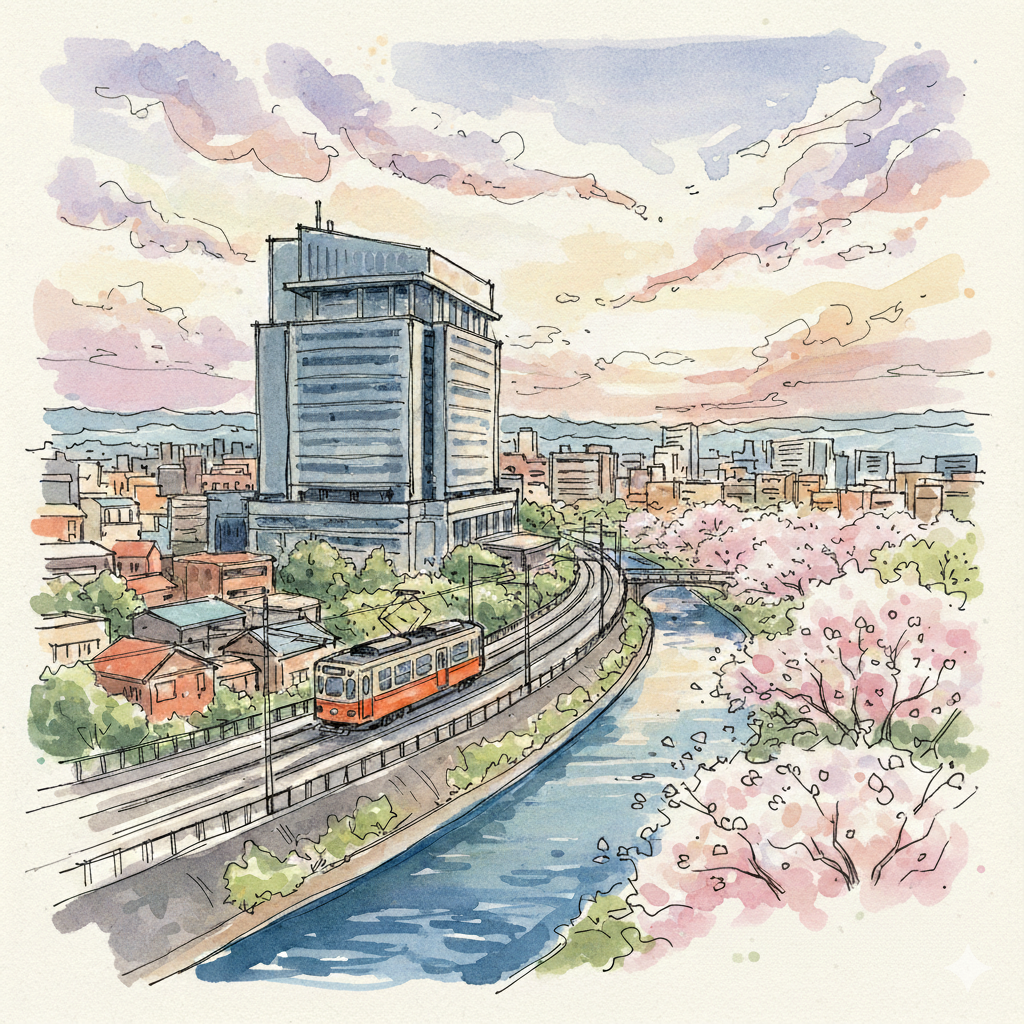

Rhythms of the Streetcar: The Living Pulse of the Toden Arakawa Line

As Oji modernized, the birth of the Oji Electric Tramway (affectionately "Oden") in 1911 democratized movement within the district. Connecting neighborhoods like Minowabashi and Waseda, the tramway became the lifeblood of the local community, linking the residents to the very factories and salons that defined their era.

Today, this pulse survives as the Toden Arakawa Line (Tokyo Sakura Tram). In a metropolis characterized by high-speed efficiency, this line remains a "mobile antique." It offers a slow-motion perspective of Tokyo’s urban fabric, stitching together residential alleyways and narrow streets that high-speed rail bypasses. The ride itself is the hidden gem; utilizing the nostalgic nickname "Oji Electric" highlights the deep-seated local affection for this gentle rhythm, which provides a tangible, steady counterpoint to the city’s more ethereal myths.

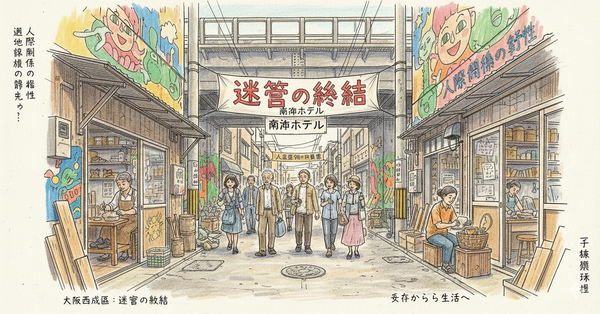

The Fox’s New Year: Folk Beliefs and the Kitsune no Gyōretsu

If industry and diplomacy represent Oji’s logic, its folk myths represent its untamed spirit. The Kitsune no Gyōretsu (Fox Parade) is rooted in the legend that Oji Inari Shrine served as the regional headquarters for all foxes (kitsune) in the Kanto area. Traditionally, it was believed that on New Year’s Eve, foxes would gather under a great Enoki tree—a site travelers can still visit today—to disguise themselves as humans and process to the shrine to pray for a bountiful year.

This myth functions as a vital counterbalance to the concrete power of industry and religion, maintaining the community's connection to the natural and spiritual worlds. Every New Year’s Eve, the local community brings this legend to life with a costumed parade. This living cultural performance serves as a "hidden ritual" for the discerning traveler, offering a glimpse into a side of Tokyo that refuses to be entirely modernized, reminding us that beneath the pavement, the ancient spirits still walk.

The Seamless City

To understand Oji-machi is to observe five overlapping layers of time: the ancient call of the deities, the white smoke of industrial enlightenment, the diplomatic echoes of the Asukayama salons, the steady rhythm of the streetcar, and the mystical parade of the foxes. These narratives do not compete; they harmonize in a rare display of urban continuity.

Oji exemplifies the philosophy of Wa-shite-ka-sezu—harmony without the loss of identity. It is a place where a metropolitan ginkgo tree can stand beside a paper museum, and a Taisho-era library can overlook a functioning 20th-century tramline. The "hidden gems" of Oji are not isolated sights but the continuous threads of history that connect them.

Can a modern metropolis maintain its continuity without sacrificing its past? Oji-machi suggests that it can, provided we are willing to read the stories written in its streets and recognize that the soul of a city is found in its ability to preserve its mysteries while embracing the light of progress.

To explore more "Deep Japan" historical narratives and hidden urban gems, subscribe to our monthly dispatch.

Traveler’s Essentials

How to Get There Access Oji Station via the JR Keihin-Tohoku Line or the Tokyo Metro Namboku Line. The Toden Arakawa Line also stops directly at the Oji-ekimae station, offering a scenic approach to the district.

Recommended Nearby Tours Maximize your visit by exploring the "Asukayama Three Museums" cluster:

- The Paper Museum: Discover the technological and cultural history of Japanese paper.

- Shibusawa Memorial Museum: Gain insight into the life and philanthropic legacy of Shibusawa Eiichi.

- Kitacity Asukayama Museum: A deep dive into the local archaeology and folk history of the Kita district.

References

- 王子神社(东京都北区) - 维基百科,自由的百科全书, accessed October 13, 2025

- 明治時代の名所!飛鳥山の桜とレトロな製紙工場 - 王子 - 紙の博物館, accessed October 13, 2025

- 飛鳥山3つの博物館, accessed October 13, 2025

- 北区飛鳥山博物館, accessed October 13, 2025

- 旧渋沢庭園 | 散策ガイド - 飛鳥山3つの博物館, accessed October 13, 2025

- 渋沢栄一の住まい | 飛鳥山とは, accessed October 13, 2025

- 旧渋沢家飛鳥山邸 青淵文庫 - 文化遺産オンライン, accessed October 13, 2025

- 晩香廬(ばんこうろ)・青淵文庫(せいえんぶんこ)【国指定重要文化財】 - 飛鳥山3つの博物館, accessed October 13, 2025

- 荒川線, 歷史, accessed October 13, 2025

- 東京都北区公式ウェブサイト, accessed October 13, 2025